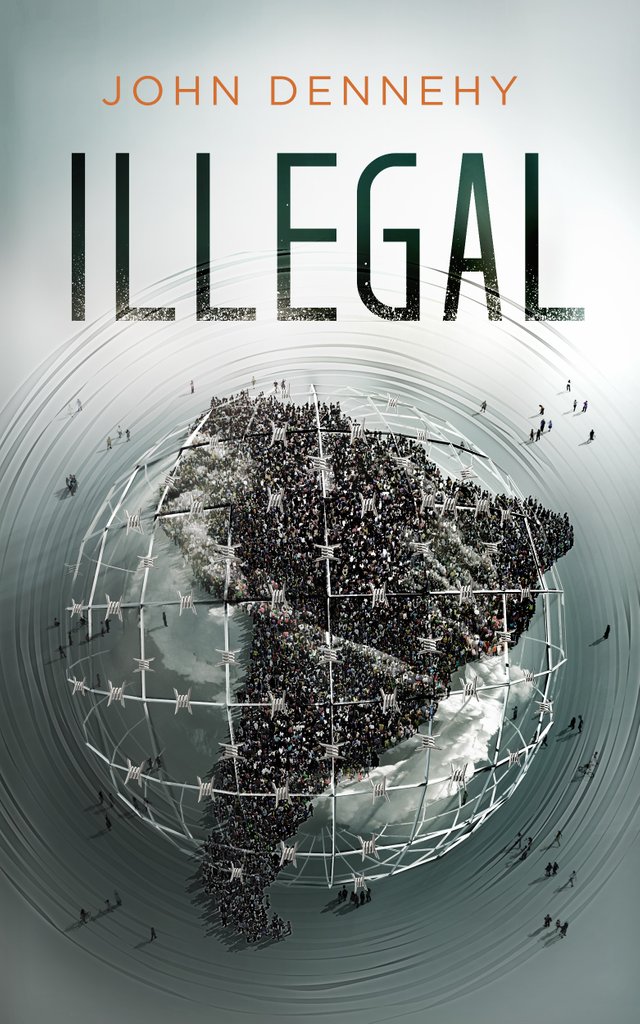

Illegal: a true story of love, revolution and crossing borders [book serialization/ Ch.2 - My First Revolution]

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the third installment [Prologue | Ch. 1] and every few days I'll give away another chapter/ section. From the back cover:

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

My First Revolution [Ch. 2]

Political demonstrations occur frequently throughout Ecuador for various reasons. Protesters often block city streets and rural highways, including major arteries such as the Pan American Highway. Public transportation is often disrupted during these events. Protesters may burn tires, throw rocks and Molotov cocktails, engage in destruction of property and detonate small improvised explosive devices during demonstrations. Police response may include water cannons and tear gas. United States citizens are advised to avoid areas where demonstrations are in progress.

–Excerpt from U.S. Department of State Profile of Ecuador (2006)

When I arrived in Ecuador there was already a political conflict brewing. It was splashed across the front pages of the newspapers and echoed in conversations throughout the country. But I didn’t speak Spanish, so it took me a while to catch on.

I started teaching right away.

“I suppose I’ll have a more advanced group, since my Spanish is so poor,” I said to Fiona.

“No. Actually you’ll be with children six to eleven years old. But don’t worry, we have a policy that no one can speak

Spanish inside the classroom, and that includes teachers.”

I must have looked unconvinced.

“You’ll be fine. I’ll show you the lesson plans; just follow those and you’ll be fine. And everyone has been in your position before. I’m sure the other teachers who stayed over from last term will be very helpful.”

The main campus was a new three story brick building on the edge of downtown. The classrooms all had new desks and whiteboards, while the teachers’ lounge had comfortable chairs and even a few couches. It was not very different from schools I had been in back in the United States, except classroom sizes tended to be smaller and all the students wore uniforms. This school didn’t require a uniform but most students came straight from their classes in the public school which did. Interestingly, not everyone wore the same uniform. In another odd twist, the students were often better dressed than the teachers—including me— who mostly wore T-shirts and jeans.

When classes began, I was surprised how easy it was. There were only nine students and everyone had a workbook and textbook. My teacher’s edition laid out lessons plans that were easy to follow. We listened to songs and the children glowed when they learned the words enough to sing along. When I read cartoon strips aloud they all laughed. When I finished one little girl would always raise her hand.

“Yes?”

“Teacher. Again please!”

The rest of the class would nod in agreement.

I asked them questions and even when they spoke with each other they mixed their limited vocabulary with hand gestures and body movement.

I asked one boy what his favorite sport was. He stood up, crumbled a piece of paper and put it on the ground in front of him.

“I like . . .” He kicked the paper between two chairs. “Gooaaaallllll!” he yelled.

“You like soccer,” I said.

“Yes. You like soccer.”

I shook my head and pointed to my chest. “I.” I pointed again. “I like soccer.” Then I pointed to his chest and said “You like soccer.”

He smiled. “Teacher. I like soccer.”

I smiled too. I had never thought about teaching before; for me it had been just a job in a faraway place whose only requirement was that I spoke English. In fact, it was just about the only job I was qualified for in Ecuador with my limited language skills and professional experience. It was oddly satisfying though to watch these children learn and grow and know that I played a small part.

At the end of my first week of classes I noticed a few people standing in front of the Universidad de Cuenca. They had bandanas covering their face and had dragged a pile of tree branches into the road. The next day there were a few more people and two tires were lit on fire in front of the blockade.

Some other expat teachers told me that people were angry with the president. “Something or other about firing the courts or changing his politics.”

On the third day of the blockades I sat down on the curb after class to observe. Burning tires had replaced the branches and there were about a hundred people. The police had set up their own blockade down the road. University students in bandanas were pounding the asphalt with large rocks, breaking it into pieces.

I was expecting them to launch the broken asphalt toward the police—and they did. But then, to my surprise, the police started picking up the stones and chunks of road and throwing them back at the protesters. Around the edges, other university students on break from class, their backpacks bulging with textbooks, watched the action unfold. The city oozed with the smell of burning rubber.

Every day the blockade grew a little bigger.

We kept the windows open during class to catch a breeze, and every day we would hear the burst of shotguns firing tear gas canisters into the air. It was like our warning bell and quickly became part of the rhythm of the lesson. By the time the police attacked the blockade, class was almost over. I forced myself to act casually whenever noises from the street invaded our classroom. I just smiled and read the next English cartoon strip as the kids followed along. Holy shit that sounds like a lot of tear gas. I wonder what’s happening out there, I would think to myself. But my students didn’t seem to notice it at all. They were all in elementary school, so either they were too young to understand or had already become accustomed to the noise of a nation in protest.

When I walked home, before I saw or heard anything, I felt the burn in my eyes from the lingering gas in the air. Each day the blockades grew a little larger and lasted a little longer.

My school had helped me find a room to rent in the city center. It was small and only had space for a twin-size bed, chair and small desk. The kitchen and bathrooms were all shared. Everyone there was a foreigner. Four of them worked at my school and the other five either worked at other schools or for NGOs. Everyone spoke English.

Two blocks from my front door was Parque Calderón, and I spent a lot of my free time there with a book, or a pen and paper. While the park served as the city’s main square and was forever bustling with people, I found the space oddly peaceful. Tall evergreens blocked out the worst of the sun and a series of small speakers played soft classical music in the background. The park was sandwiched between an immaculate federal building with crisp flags hanging off its balcony and the Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción. The massive cathedral dominated the cityscape and was the site of a 1985 mass by Pope John Paul II that drew tens of thousands of worshipers from all over the country and was still being talked about when I arrived—which also explained why almost every Ecuadorian male I met in his early twenties was named Juan Pablo.

About two weeks after I arrived in Cuenca I was sitting on a bench in the park when the more moderate counterparts to the student radicals began showing up in large numbers. Lucy, a teenage girl with pigtails sitting next to me, was clearly excited, and she spoke enough English to carry on a conversation.

“What’s going on?” I asked. “I mean, I’ve seen the protests at the university, but I’m in the park every day and I’ve never seen anything here.”

She took her eyes off the growing crowd long enough to smile at me playfully and ask, “You didn’t hear?”

She went on without pausing for my response, turning her attention to the crowd again.

“The mayor was on the radio this afternoon and he came out against the president. He told everyone in the city to come to the park to protest.”

I kept my eyes on my new friend, who had spent a year in the U.S. as an exchange student. She paused and grinned at me again. She could see how fascinated I was with all of this, how I hung on her every word. She tried to act nonchalant but seemed almost giddy at the chance to explain things to me.

“The government’s going to fall,” she said.

The crowd chanted, “¡Fuera Lucio!—Lucio out!” calling the president by his first name as they marched around the park. More people continued to show up, filling the empty roads that outlined the square, and a crowd massed in front of the federal building. Police in blue-gray camouflage uniforms and military-style hats stood shoulder to shoulder between the building’s massive pillars, staring out onto the crowd with emotionless faces.

“Lucio was supposed to be for the people,” Lucy told me. “He was supposed to be different, but he just wants money and power. Before he was president he led a revolt of the people. He said the North Americans would have too much influence here. And now look at him!” Her voice rose. “He is trying to sell my country to the Yankees.” She seemed very calm, almost distant most of the time, but for short bursts it was clear that she was as angry as everyone else.

In 2000, Ecuador’s currency, the sucre, was experiencing rapid inflation. President Jamil Mahuad announced he would abandon the sucre in favor of the U.S. dollar, which upset a lot of people. Besides being seen as a loss of sovereignty, the change would mean that people’s savings, the thousands of sucres accumulated over a lifetime, would now only be worth a few dollars. Large street protests erupted across the nation. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) led a march on Congress on January 21st. Then a Lieutenant Colonial in the Ecuadorian army, Lucio Gutierrez, disobeyed his orders and his unit stood aside and allowed protesters to take over the national parliament. Guiterez joined the protesters’ occupation and formed a three-man junta alongside CONAIE president Antonio Vargas and retired Supreme Court Justice Carlos Solórzano. The three-man junta declared Mahaud’s presidency invalid and ruled the nation for three hours. After successfully stripping the president of his power and forcing him to flee the country they peacefully handed power back to Vice President Gustavo Noboa for an interim government. The success was temporary however; a few months later the government went forward with the ‘dollarization.’ The armed forces also jailed Guteriez for his role in the coup, before granting him amnesty after serving four months. With nationwide recognition and the support of a leftist coalition that included the powerful indigenous movement, Guteriez was elected president in 2002.

Remembering small pieces of conversations with other teachers and clips from newspaper articles, I asked Lucy a question. “He fired the Supreme Court too, right?”

“Yeah, that was the worst part. He only won the election because all the left parties supported him, but then he abandoned them for the PSC [a conservative political party] and started stealing funds from them to grow his own party. The courts were going to impeach him, so he fired them. He’s not even allowed to do that. He’s just as corrupt as all the other presidents we have thrown out.”

Lucy was still explaining everything to me when a caravan of men in suits arrived.

The mayor and other local politicians walked toward the protesters, waving, expecting to be greeted as heroes. But the chant abruptly changed to “¡Que se vayan todos!—They all must go!”

The crowd flowed toward the new arrivals, blocking their path. The politicians immediately turned around and hurried away in their black Mercedes Benzes. As they disappeared behind tinted windows, the crowd roared.

I stayed in the park after Lucy left and continued to observe, fixated by what was happening in front of me. Above the noise, I heard three people loudly chanting something new as they snaked through the street. More people joined them, their voices becoming louder as the moving mass grew more distinct. Dozens strong now, they made their way out of the thick crowd in front of the government building, around the square and back again. By the time they made a full circle around the park the chant had reached a fever pitch and the crowd yelled out in unison, “¡Todos los dias hasta que Lucio se vaya!—Every day until Lucio leaves!”

As I was leaving the park I bumped into Peter, a foreign journalist from Ireland covering the protest. His collared shirt was untucked and his red hair was knotted and falling onto his forehead. He stopped to ask me my take on the situation.

“I’ve only been here a couple of weeks, but I’ve never felt this energy before,” I said.

He had a notepad and pen out but didn’t write anything down. “Yeah. I’ve been to a dozen countries covering civil unrest and protests, but you’re right, there’s something different going on here—something bigger.”

Staring back into the crowd, he invited me for a drink.

“Sure.” I said.

He led me to a restaurant a few blocks away. “I had breakfast here this morning. Good food,” he said. The menus were in English and other foreigners were scattered around.

“So why Ecuador?” Peter asked after we ordered a couple of Cuba Libres.

“It was fairly random actually. I just wanted to live in a place completely different from everywhere else I have known.”

“But that’s the end of the story. Where does it start? No one picks up and moves across the world without a good reason.”

“Ah, well, I suppose the start of the story would be September 11th.”

Peter nodded. This was what he wanted to hear. “Were you in New York when it happened?”

“No, I was at school, about two hours away.”

“So you saw it on the news?”

“Well my girlfriend called me,” I told him. “She didn’t even say hello. She just asked which building my dad worked in.”

“Even in Ireland it was all anyone was watching,” Peter said. He explained how his mom was living in Michigan and he tried calling her but the line was down.

“Same for me. I couldn’t call any of my family in New York because the circuits were overloaded.”

“Yeah, I remember that. I thought it was part of the attack at first.”

I nodded. “Me too. And when I turned on the TV the news was still reporting that other planes were in the air. And in the background people were jumping out of buildings. It didn’t feel real.”

“Yeah, that day was fucked.” Peter tilted back his drink and waved at the waitress for another. “Was your family alright?”

“Yeah. My dad saw the second plane hit and got stranded in Manhattan after the trains shut down. My Uncle, who’s a cop, was actually at Ground Zero helping people evacuate before the towers collapsed, but he ran fast enough to make it out alright.”

“Shit, he was lucky.”

“Yeah.”

We were moving off track and Peter, ever the journalist, brought us back. “But, how did all that land you here in the middle of these protests?”

“Well, September 11th made me into an activist,” I explained. “I wanted to help make a world where that could never happen again.”

Peter nodded. “And then the Iraq War and George Bush and all that.”

“Yeah. People wanted war. They actually wanted it. September 11th changed a lot of people, and I didn’t like those changes.” I told Peter how my uncle, the one who escaped the falling towers, spent weeks searching for body parts flung from the planes onto Manhattan rooftops and went to tons of funerals for all the cops who died. “He had it rough, but all he wanted afterward was revenge.”

Peter frowned and shook his head as I sipped my beer.

“Everyone was flying American flags,” I continued, “but it wasn’t patriotism—it was nationalism.”

“What do you mean?” Peter asked.

Patriotism is pride in one’s nation, I told Peter, but nationalism is the belief that your nation is better than the others and can play by different rules. Nationalism means that you value life in your country above others and that you believe your culture is superior and should replace others, by violence if necessary. It makes us seek vengeance over one death of ours but feel indifference when another nation suffers hundreds of deaths. It makes us think we are always just and innocent and leads to cultural imperialism and war.

Peter nodded. “That’s some heavy stuff. In Ireland, we use the word nationalism with a different meaning, but yours makes sense too.”

I nodded. “I hated it. I packed my bags as soon as Bush was re-elected.”

A week after I witnessed the protest in the park with Lucy, I heard about the General Strike. The school I worked at was foreign-owned—Canadian—and only hired foreign, native English speakers to teach. Outside the teachers’ lounge was a corkboard that was always filled with photocopied pages from the Lonely Planet or printed out news articles from U.S. newspapers. But that was all taken down. Tacked to the center of the board was a single sheet of paper from the U.S. embassy. It read that the opposition was planning an indefinite general strike for the cities of Quito and Cuenca and that U.S. citizens and businesses may become targets. It warned all Americans to keep a low profile.

A chill of excitement passed through me.

The school didn’t wait for the official start of the strike on April 12th; next to the notice from the embassy was another one from the school: all classes were canceled indefinitely.

That afternoon I went with some of the teachers for drinks in place of class. About 3,500 foreigners were living in Cuenca at the time, mostly from North America and Europe, and expat pubs were scattered all over downtown.

We passed a group of men pasting red posters to store windows. The only words I recognized were “STRIKE” and “REVOLUTION” next to the following day’s date. There was a pickup truck parked down the road with stacks of thousands of these flyers and people were grabbing piles of them and setting off down different streets.

We ducked into Inca Bar, a popular expat pub downtown and set up at one of the long wooden tables stained with English graffiti.

“We’d better stock up on liquor before tomorrow,” joked David, a balding North American in his early thirties. Everyone forced a laugh but the mood was subdued; none of the teachers had ever witnessed a general strike before and the embassy notice had put them on edge.

“If anyone wants to stay with me, there are some extra couches and plenty of room at my place. It’s mostly Americans and Germans anyway, so everyone speaks English,” said Marisa, a pale skinny woman from Indiana just out of college.

“We should stick together.”

“It’s bad enough we have to walk the long way to class to avoid the university. I hope the country can get its act together soon or I’m leaving,” said a second woman I didn’t recognize.

I didn’t say anything but I was already plotting a long day outside. I’ll go to the park first—and I bet there will be a lot of action near the university. My beer was more celebration than distraction.

The next morning I walked to the park—it was only five short blocks from my home. Riot police stood in neat lines in front of the government buildings and two tanks were parked on opposite corners with more riot police clustered around them. But that was it. There was not a single protester. In fact there wasn’t a single person; just me, some riot police and tanks.

I walked around downtown and it was similarly deserted. I passed a few people on the sidewalk and saw a handful of cars drive by but none of them looked like protesters. Scraps of red paper hung from lines of tape on closed store windows. Someone had ripped down most of the posters.

This is a general strike? Well that was a bit anti-climactic, I thought. I went home for lunch.

In the evening the buses began to run again. It started to look like defeat. I walked down to the university, and there was the usual blockade set-up. There may have been a few extra people than usual but still only a few hundred in total. There was something different though. Normally the students kept the fire fairly small, just big enough to keep the flames going and throw off some smoke. This night, the flames reached over my head. The protesters were burning their reserves. I sat down on the curb behind the main group and took out my notebook.

Despite the fire and slightly larger crowd the space was quieter. It felt like the end of a long party when your own bed starts to seem more attractive than another drink.

A small group broke off from the crowd and walked to a main street nearby where buses had begun to run again. They stopped a bus, made everyone get off and drove it to the barricade where they parked it in front of the line of flames. When people realized what was happening they began to cheer. The masked students walked off the bus and threw the keys into the river. “¡Viva el paro!—Long live the strike!” They shouted.

The crowd erupted. Pockets of students broke off and ran to other roads. They hijacked more buses, parked them in intersections and walked away. The mood shifted dramatically. It was the most excited I had ever seen the crowd. People were yelling and dancing in the street.

This would never happen in the U.S., I wrote in my notebook. People are hijacking buses! And it’s not only accepted by everyone here as legitimate but inspires more action and has reenergized the crowd. In the U.S. a person would earn a few years in jail for hijacking a bus, and I’m sure many protesters themselves would condemn the act. Shit, if people had started hijacking buses in Hartford or New York, I might have even told them to stop, and I was way more radical than the average protester there. I might be changing my mind though—I’ve been too caught up trying to follow the rules and be a ‘good’ dissident. Real change won’t come from within, it didn’t back home and it won’t here. But now is probably a smart time for me to leave; I’m excited to see what tomorrow brings.

The next morning there were small crowds in the street and the mood was optimistic. I went to the blockade that was set up in front of the university to try and talk with some of the students. It was the biggest I had ever seen it. I was struggling to speak to a few of them with my mostly non-existent Spanish when a bilingual student came over and began to translate for me. Luis had long black hair and wore a red bandana over his face. He had family in New York and had been visiting them and speaking English from a young age.

“Lucio is a traitor, but they are all traitors,” Luis translated his friend for me. “After we throw him out we need a leader who comes from the social movements, someone who isn’t part of one of the political parties.”

I nodded my head, but before I could reply the first burst of tear gas shot toward us. Police wearing masks had snuck up along the side streets and also charged from the front—a few of them were shooting tear gas pellets from rifles.

I ran with my eyes closed and my lungs burning through clouds of gas and into the university. In Ecuador, police are banned from entering university grounds, which made it a safe zone and the most logical place to put a blockade in front of. I found the group I had been conversing with when the gas chased us apart; I was happy to see some familiar faces in this place where mine didn’t fit in. They were standing at the edge of a large concrete sidewalk that extended from one of the university entrances. I nodded my head toward Luis and the others and collapsed onto the grass next to them. A boy of no more than thirteen lit a cigarette, walked around the circle and blew smoke into everyone’s eyes.

“It helps take away the gas,” Luis told me. The boy bent down, cupped his hands around his mouth and gently exhaled the cigarette smoke onto my eyes. Luis said something I didn’t understand to another student in the circle who rummaged through his bag and took out a green bandana. Luis handed it to me, “Put this on and cover your mouth and nose. It helps.”

As a water bottle was passed around to wash out our eyes and mouths Luis sat down on the grass and explained to me what was happening. A couple of his friends sat down with us, half paying attention while they rested.

“The blockades start every day around lunch time. They start small and grow through the day; always the same,” Luis explained. But that day, he told me, when a few people went out early and started dragging some branches into the road, a car pulled up. When the students approached the car to tell them to go around, several plainclothes police jumped out and started beating the students. They ran into the university for protection but the police followed. Luis added, with more anger, “The police are not allowed here!”

“So what happened?”

Luis pointed a few feet away, past his cousin examining the welt on his stomach where one of the tear gas bullets struck, to the concrete sidewalk. There were fresh blood stains.

“There. That’s where the cops caught up to them; that’s the student’s blood,” he said. “Word spread fast after that. Someone came into my class and gave us the news. The class just stopped and a bunch of us ran over here but the injured students were already being helped, so we went out into the street and built the blockade.”

The gas lifted while we spoke. The police had taken back the parked buses and retreated. Luis tied a white shirt over his face and we walked back into the street. Other students had already split off to get more buses. Luis picked up two fist-sized rocks as we joined the students who were already blocking the street with their bodies where the bus had stood.

With the road cleared a tank began moving toward us. I could feel a slight rumble in the pavement as the tank approached. The engine and gears screeched as they bounced over debris in the road before the sound was drowned out by the clank of rocks smashing against its metal. Luis’s eyes stared at me through the hole in his mask. He put one of the rocks in my hand and said, “Fight with us,” as his eyes shifted back to the quickly approaching tank.

I had translated an English phrase that I liked before I went to the protest, and even though our conversations had been in English, I read out of my notebook in his language: “Mis palabras son mi arma— My words are my weapon.” I handed the rock back to Luis.

He nodded his head. I had told him earlier that I wanted to write an article about all this for a U.S. audience. In the next moment he wound up and threw one of the rocks full force. The stone smashed into the metal grating in front of the windshield and bounced off. A dozen more clanks of stone against metal followed as more students let go with their projectiles.

A few days later I was in the park chatting with Sonia, another teacher from my school, when families began to arrive for their daily dissent.

Sonia was from Scotland and had frizzy blond hair, a curving body, charming accent and a sense of adventure. She was the only other foreigner I knew who was excited rather than scared by the protests. “This is the kind of thing you read about in other places, so if it happens here I wanna see it,” she told me the first time we stopped at the blockade together. We were walking home from school and she was carrying Scrabble with her—a prop from class earlier that day— when we sat down on the curb for a few minutes to watch. “Let’s set this up and start playing. Come on now, it’ll be fun,” she told me. The police tank started barreling our way and we had to hastily throw the board and stray letters into her bag before we could start, but I loved her spirit. She made me feel sane.

Mothers and fathers holding their young children’s hands paraded around the park, calling for the resignation of the president. Then, suddenly, hundreds of students from the blockades appeared in commandeered buses; it was the first time these two groups had come together. Before all the students could exit the buses, the police started throwing tear gas grenades into the park. Everyone scattered. Within seconds the entire square was filled with a suffocating cloud and I lost sight of Sonia while trying to escape. I heard her scream before she disappeared into the poisonous fog. Armed with gas masks and long, wooden sticks, the police chased the scurrying groups away from the park and then through the streets. I closed my eyes and ran.

Those first few minutes were extremely chaotic. Tear gas was being fired without pause, police were swinging their three-foot-long batons wildly and beating anyone they could catch. Young children who had come to the park with their families were crying. Some had become separated from their parents and were hysterical.

The type of tear gas the police were using had been developed as a military weapon and was banned in my home country—this felt nothing like getting gassed in Washington D.C or Boston. Once the gas hit, it felt as if a sharp knife was being scraped against my eyeballs and I reflexively crunched my eyelids closed. After a few seconds my body started to violently dry-heave, as if my lungs were trying to jump out of my chest.

Every few seconds I blinked my eyelids open to orientate myself and each time the scene was worse. The police had stopped tossing the bulky tear gas canisters and started using shotguns that fired large oval bullets of concentrated gas. The bullets didn’t travel far, but at close range they were powerful enough to break your ribs. Once fired, the gas shot out into the air through small holes in the bullets. The pressure pushing the gas out was so great that the friction heated up the bullets to the point that they often burst into flames. Most of them bounced off the trees or skipped to a stop on the ground but some of them struck the parents, children and students trying to flee. With my eyes still closed I heard screams behind me, and bullets whizzing past my head.

It was the first time I was scared.

As the police chased us through the streets, the different groups began to find themselves. The initial panic was being replaced with adrenaline. Within an hour the police had retreated and protesters had set up barricades at all the major intersections downtown.

I recognized a student from the university blockade and was able to borrow his phone to try to get in touch with Sonia. She was safe at another seized intersection at the other side of downtown.

At my little occupied intersection, the dissidents made large fires in the streets and danced around the flames. I stayed on the edge, scribbling into my notebook.

Someone had brought a radio out just in time to hear reports that sections of Quito had been overrun by protesters; cases of beer had already been bought at the corner bodega and people sprayed their beer in the air. I stayed on the outside of the action and observed with joyful fascination and a bit of envy, wishing that social movements were as strong and brave in my country. Thirty minutes later the radio reported that the police ring around Congress had been broken and the building occupied by protesters. As the night wore on and fear was fully replaced with excitement, entire families flowed out from their apartments and joined the street parties all over Cuenca. The government would never regain control of the city.

El Universo, the nation’s largest newspaper, carried these headlines the next day: Tres Muertos y 307 Heridos Dejaron las Manifestaciones (Three Dead and 307 Injured in the Protests); Estudiantes se Tomaron el Congreso Nacional (Students Take Congress); Fotógrafo Chileno Murió Asfixiado (Chilean Photojournalist Dies of Asphyxiation).

In the morning the national police chief resigned in protest over the heavy-handed tactics of the government. Many local police and military officers walked off the job, and the ones who remained did nothing to stop the protesters from occupying government buildings throughout Cuenca.

That afternoon the president fled the country and his government collapsed.

--

I'll be releasing the entire book this way but if you want to buy the paperback with Crypto-currency, email: [email protected] with your mailing address (U.S. only) and your preferred crypto and I'll respond with a wallet address and mail the book. $10 USD including shipping, limited time/ crypto only

interesting ...

Very.

Love maximum time make as a illegal way, here it's not a basic ideal conception

Wow. Excellent writing. Going to come back to reread this part....

excellent story johndennehy ( 60 ) You are a great writer, continue like this I´m also a writer and I wish that you to be a best seller

Thanks @artistacreativo I just started following you, hope to see some of your writing now.

Incredible!😌

following...

Such an awesome story . Love to read this. Keeps it up once again with a new story.

What an interesting and a captivating story.

You got a 30.60% upvote from @upmewhale courtesy of @johndennehy!

Earn 100% earning payout by delegating SP to @upmewhale. Visit http://www.upmewhale.com for details!

https://steemit.com/life/@fahdq888/paris-the-capital-of-the-lights