The Nazification of the German People: An Analysis of Voter Incentive and Catholic Influence

For any who may be curious as to how Hitler was democratically elected and to what extent the Catholic Church had an impact on Hitler's political success.

The Nazification of the German People:

An Analysis of Voter Incentives and Catholic Influence

It is one accomplishment to win an election by maintaining the status quo or by altering minor adjustments to the state’s political or economic system; it is an entirely different undertaking to bring forth a dictatorial government and win by democratic majority of the political votes. In essence, the German people cast what would have been their final vote in the year 1933 had the Nazi party remained in power until today. How was it then, that a people democratically voted to give up their rights to democracy? How did they put forth a total sense of trust in one man who would eventually lead the country to ultimate destruction? The circumstances that led to this drastic change and how the Nazi ideology took root in the German people were executed on many different platforms, varying between social classes in the Weimar Republic. This included, but was not wholly restricted to, financial and religious incentives. This paper will conduct an analysis as to how the Nazi regime managed to nazify the German people and gain the support for a war machine unprecedented in modern times. In addition to the religious sects’ support for the Nazi party, the economic turmoil of the Great Depression provided a greater leaning towards radicalism in ideology in hopes of revitalizing Germany to the great power it once was. The SA-- Hitler’s early political police-- attracted many additions to the party through their financial handouts for enlisting in the SA. It was thus through religious manipulation and the need for security in a time of rampant political violence and economic uncertainty that subsequently led to the nazification of the people. However, it was force itself that was the ultimate generator for support, which would allow for the total take-over of the Republic and its citizens.

A critical aspect of the initial voter support that must not be overlooked in the rise of the NSDAP was conducted by the Catholic and Lutheran denominations of the Christian faith. The German Catholic Church saw the anti-religious SPD and BVP party as the greatest potential threat to the well-being of the German people and thus consequently forged an early alliance with the Nazi political apparatus. This unlikely friendship would eventually backfire once the the Nazis had absolute control and public opinion and religion became completely irrelevant to political decision making. It is not hard to comprehend that the National Socialist and Christian ideologies are incompatible on multiple levels, much like that of National Socialism and Communism. Perhaps the greatest and most obvious difference is that one requires ultimate obedience to a political leader, the other puts a deity above him. It can be deciphered then, that this was somewhat of a sociological tendency in the common saying that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” and both sides propped the other up on a pedestal in which they knew the other could not possibly fulfill. The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact can be seen as a parallel in this regard, where Hitler and Stalin divided Poland in accordance with a non-aggression pact. Hitler, on the basis of his ideology, knew that the Soviet Union was an empire of Jewish Bolshevism and that peace with the Soviet Union could never be a permanent solution. Thus, when the breakout of war against the French and British went extraordinarily in his favor, he broke the non-aggression pact prematurely and invaded the Soviet Union. The support for the NSDAP was not limited to solely the Catholic Church, as the Lutherans sought to gather support for the Nazi party as well. This is a prominent feature when analyzing the nazification of the German people because it set forth an attractive moral basis hidden behind the realness of what was to come, which was a totalitarian state that functioned off the intrinsic fear of the people. To understand the anti-semitism inherent in the Catholic Church by the time of Hitler’s rise to power, one must look back to the 1918 revolution in Munich. It was here where the book, Das Kommende Reich, (The Coming Reich) was authored by the popular Bavarian Catholic priest, Franz Schrönghamer Heimdal, twenty two years before Hitler’s consolidation of power. In this book he laid out the “programmatic blueprint for the ecumenical yet distinctly Catholic-oriented spiritual rebuilding for Germany.” He contrasted the purity of Christ and his true followers with the immorality of the capitalist Jewish spirit with invigorated revivalistic urgency. In 1922, Wilhelm Vielberth of the rival BVP political party attempted to exploit a potential weakness in what he saw as utter hypocrisy and drew correlations of the Nazis with anti-Christian volkisch movements in Germany. However, the Nazis claimed that they were indeed on the side of the Catholic Church. The Nazis stated that “the battle, which according to Catholic teaching takes place before the judgement seat of God, between Christianity and anti-Christianity, between idealism and materialism-- this is the battle we National Socialists want to wage.” Schrönghamer refuted Vielberth’s assertion by stating that the BVP and Center party were of course problematic for Catholics, not for reaching out to believing Protestants, but because of the “abyss of hypocrisy” which was forged by their cooperation with the Jews and socialists. At official Nazi Christmas celebrations, Hitler explicitly emphasized the Christian combat mission of the NSDAP in which they must invoke Christ’s heroic spirit and not be Christians in word only, but rather “Christians of the deed and of the sword.” Hitler’s correlation of Christ and the warrior spirit fueled the passion of what was to persuade a great many voters in the coming elections.

In what would seem like a peculiar alliance in regards to ideology, the common anti-semitism within the Church certainly allowed it to develop a more like-minded bond with the Nazi party. This was revealed by some major priests in Germany, such as Magnus Gött, a radicalist from Lehenbul in Bavaria. Hastings states that, “...Gött had studied philosophy and church history both in Dillingen and at the University of Munich, coming under the influence of the Reform Catholic leader Joseph Schnitzer.” His radical outpourings were revealed almost immediately in his contribution to the Leagauer Anzeiger, where he demonstrated a prominent sympathy for the working classes and began his anti-semitic writings. In agreeance with Gött, Schrönghamer expressed his support for the Nazi party in a 1923 article featured in the Beobachter, claiming that “the NSDAP was perfectly compatible with the Catholic faith in both theory and practice.” Hitler, who undoubtedly recognized the opportunity that was handed to him, pressed his advantage on the Christian support and in 1922 published a pamphlet and explicitly emphasized the “warrior identity of the Lord and Savior in combatting the Jews.” In a major address on April 6th, 1923, Hitler defended this position by stating, “We are characterized as anti-Christian by the party that most seriously threatens Christianity through its connection with Marxist atheism: the Center Party… We must once again raise up Christianity, but it must be warrior Christianity. Christianity is not the teaching of silent suffering and burden bearing, but rather of battle. As Christians we have the duty to fight against injustice with all the weapons Christ has given us; now is the time to fight with fist and sword.” It was thus through religious fervor that Hitler was able to sway Christians to his side and awaken the image of the “heroic Aryan Christ driving out the Jewish money-changers.” The Christian-Nazi alliance certainly helped Hitler gather early supporters for what would be a radically anti-Christian party once he seized power.

In addition to the Christian persuasion, another key factor in determining how the NSDAP managed to rally such a great percentage of the population was their ability to consolidate other political parties and like-minded social movements. After the Beer Hall Putsch and Hitler’s jail sentence, his re-entry into political life in early 1925 was seen as negligible and the party suffered accordingly. The volkisch parties, (other anti-semitic nationalist groups) attempted to compound on Hitler’s early popularity but were unable to achieve much success in the 1924 elections. Even after Hitler had regained absolute control over the Nazi party, they still struggled to gain any significant amount of voters, polling only at 2.6% of the national vote in the 1928 elections. One of the strategies the Nazis used to recover so quickly was their use of local networks that volkisch movements had left behind since the Great War. They effectively managed to tap into a demographic of the population that was still zealous in their nationalistic beliefs and reformulate them into one body. After the major political candidate Ludendorff had polled terribly in the 1925 election, Hitler pushed his bid to the forefront of the movement. Kershaw states that, “the volkisch movement itself, in 1924 numerically stronger and geographically more widespread than the NSDAP and its successor organizations, was not only weakened and divided, but had now effectively lost its figurehead. At first, especially in southern Germany, there were difficulties where local party leaders refused to accede to Hitler’s demand that they break their ties with volkisch associations and subordinate themselves totally to his leadership. But increasingly they went over to Hitler. Most realized the way the wind was blowing. Without Hitler, they had no future.” In regards to Hitler’s personal character, he wooed many with his incredible ability to act accordingly to the social situation. Kershaw states that, “Those who came into contact with Hitler, while remaining a critical distance from him, were convinced that he was acting much of the time. He could play the parts required. He was a kindly conversationalist, kissing the hands of ladies, a friendly uncle giving chocolates to children, a simple man of the people shaking the calloused hands of peasants and workers, one of his associates later recalled.” When giving speeches, Hitler expressed a method of audience-taming effects such as purposely delaying his entry to a packed hall, orchestrating his rhetoric with colourful phrases, and displaying distinctive gestures and body-language. A pause at the beginning of his speeches would allow for tension to mount, followed by hesitant undulations of diction and staccato bursts of sentences all while he acted with his hands to emphasize the key points in crescendo. Kershaw concludes that, “The irresistible fascination that many-- not a few of them cultured, educated, and intelligent-- found in his extraordinary personality-traits doubtless owed much to his ability to play parts. As many attested, he could be charming-- in particular to women-- and was often witty and amusing. Much of the time it was show, put on for effect. The same could be true of his rages and outbursts of apparently uncontrollable anger, which were in reality often contrived.” These fine intonations of personality control to mold to the situation he was positioned in allowed Hitler to entertain his audiences while delivering his core messages. Hitler’s rapid adaptation to the new political scene spurred his movement and attracted many spectators. His first public appearances in February, 1925 were dramatic successes. The Nazis capitalized on Hitler’s speeches, which were becoming somewhat of a theatrical spectacle, and pressed special trains into service to curtail logistical troubles for Germans that wished to see Hitler speak. Altogether, one of the main aspects of attraction to the Nazi movement was not only that he commanded loyalty, but he commanded interest as well through his extremely charismatic performances.

The NSDAP were extremely effective organizers, which separated them from the turbulence of other political parties and their schisms. They pandered to the specific demographics that had been hit hard by the depression, such as the farmers and shopkeepers, and united them in coherence with their ideology of the general interests of Germany in addition to their own interests. The unifying ideal was known as Volksgemeinschaft. This ideology was focused primarily on regrouping the German worker back into the Volk, or German race. This is one of the significant efforts that separated the Nazi party and helped boost the voter population. The Nazi party’s attempts to make appeals across class lines made it different from its closest political rivals. The early support for the party consisted of a significant number of student groups in German universities, as well as just young people in general, which in turn tore apart families on the basis of ideological differences. In one such circumstance, a middle class youth recounted that, “there was no way to avoid a fight with my father, so I left my parents’ house and moved in with my eldest, married sister.” In other circumstances, new politicized Nazis managed to convert their families to the popular ideology as they saw it was not just for the cause of a political party, but for a nationalist revolution. As the Nazi ideology spread through the classes, it multiplied within the families. The Nazis engaged the public with handing out pamphlets and discussing their political views. They gathered the support of workers, farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers and did this not so much in an attempt to appeal to specific occupations, but to get to know the ‘little man’ in order to stitch together the social divisions of the German people. In the midst of the economic crisis of 1931 and 1932, the simple Nazi slogan “Bread and Work” rallied even more supporters. These campaigning strategies ultimately allowed the NSDAP to do better among Catholics than any other non-Catholic parties and better among workers than any other non-socialist party.

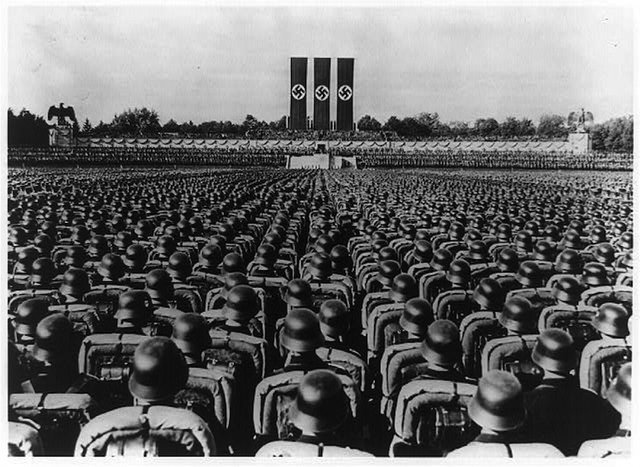

Just how much of an effect Hitler alone had on the masses is a serious topic of debate. John Hilden and John Farquharson state that political scientists have disagreed to a large extent on how much the socio-economic vacuum present in the Weimar Republic was a direct result for Hitler’s ascendancy to power. They claim that when historians attempt to analyze fascism and totalitarianism, they tend to fall into the trap of regarding national socialist ideas as a “fixed and constant system… That is not the way to arrive at a proper understanding of the part which ideology played in German society between 1933 and 1945.” Such an argument insists too much on Hitler’s role in the movement, due to the emphasis on the leader and personality cult in totalitarian governments. Many of the NSDAP’s motives were concealed to the masses during major speeches. Hilden states, “National Socialists were unable to move directly towards an open declaration of their goals at least partly because of the survival of Marxism and liberalism, not to mention Christianity, among wide sections of the German population… Radicalism and anti-semitism were much less obvious in Hitler’s speeches. The same is true of attacks on the Christian religion, which were replaced by a more overt onslaught on Marxism. Concealment of some of the National Socialist aims were essential in order to rally electoral support.That in itself made it more difficult to declare openly the true purpose of the movement even after coming to power.” One of Hitler’s own strategies in an attempt to nationalize the German people was through mass rallies and marches. In one case in 1933, the Ministry of Propaganda had taken significant responsibility in organizing the Annual Harvest Festival, as opposed to the Ministry of Food and Agriculture. One of the primary focuses of rallies such as these was that they encouraged the participants readiness to lose their personal identity in the drive towards a common goal, especially when Hitler was present.

To properly understand the possibility for an attraction to such a party like the National Socialists, one must delve into the economic circumstances of the era. The Great Depression hit Germany hard, and in combination with the mass inflation due to the post war years, the German people were in chaotic disarray. “During the winter months of 1929-1930 the unemployment curve dramatically began to exceed the seasonal figures of the previous year. Throughout 1930, an extra two million unemployed haunted Weimar politics and, following the emergency decrees of the austerity program of Chancellor Heinrich Bruening, the figure grew to 2.9 million by March 1931, and to 4.4 million in November the same year” The zenith of unemployment reached a height of six million able-bodied and skilled workers, and teenagers and young adults turned to thievery and prostitution as a way to make ends meet. Older people became beggars or went door to door desperately attempting to sell dry goods. Sex offenses increased, minor property violations multiplied, and the asocial elements of society accumulated in the streets of Berlin. In the political sphere however, the Nazis were not the only ones to exploit the misery of the masses, as the KPD communists put forth every effort to rally the masses to their cause as well.

A great hatred began to brew between the proletarian masses and the bourgeois job holders. Both sides of the political spectrum were violently opposed towards the current system of government. It can be deciphered then that there was an urgency for a repair of society, a new order to bring back the sense of what it meant to be German. Surely sitting around at home or huddling around a street bench spectating a game of cards was not what life was meant to be. “Political action born from economic despair got an early start among north German farmers and small business interests. Radicalized through their plight, farmers in Schleswig-Holstein initiated tax strikes and resistance to farm foreclosures… In the end, Protestant rural areas tended to vote far more heavily for the Nazis than did urban areas.” In addition to the sentiments of the farmers, small businessmen such as shopkeepers, independent craftsmen, or apartment-house owners began early to defect from their traditional liberal party loyalties, as their economic position became ever more marginal, and to rally to various middle class interest parties.” These incentives to protect the self-interest of the individual was one of the psychological strategies the NSDAP deployed in order to attract even more votes.

Furthermore, the Nazis rewarded those well who invested their time to the movement. William Sheridan Allen expresses this notion in his book, The Nazi Seizure of Power, when he describes the financial attraction to becoming a Nazi speaker. In 1931, the Nazi Speakers Bureau tightened and would only allow official speakers to make remarks at official Nazi meetings. Only those with identification cards could speak, which were issued after having passed a test. “Since those who passed could then earn the standard fee of seven marks per speech-- good money in those depression years-- plus transportation, meals, and lodging, many Nazis strove to obtain official certification.” In a time of economic crisis and mass unemployment, this feature alone quite possibly may have attracted natural orators to take up the Nazi cause for a decent pay. Merkl describes the youth as being particularly vulnerable to the disillusionment of unemployment, especially when the full-fledged welfare state had been completed with the Law on Employment Services and Unemployment Insurance in 1927, consequently reducing unemployment benefits due to the impact of the Depression. Merkl states, “Thus, when the standard of living has dropped to such a low standard, then all inclination to listen to lectures, arguments of state, or the voice of reason will disappear with psychological necessity.” A major attraction towards the right-wing nationalist parties came from the ex-soldiers who had been a product of the war fervor in WWI. “The front-line soldier’s ideology was nationalistic, undemocratic, and totally lacking in the kind of political insights needed in the midst of the Weimar crisis. At the same time, it fostered an assertive arrogance toward other generations, the pre-war politicians, and the vast numbers who had grown up without the doubtful benefits of an education in the trenches of the Great War.” In addition to the war veterans, the youth of the post war period accounted for 1/4th of the adult German population and were equally as unforgiving towards democratic means of political discourse. An editorial writer noted his observances in a newspaper column: “Our youth is anti-reason...simply not interested in the philistine reasonableness of its elders... who in turn are too smart to make room for youth and will even close the door on its legitimate aspirations...The new generation also knows nothing of liberalism and can hardly be expected to. They enjoy the most liberal of constitutions and just take its freedoms for granted… What does the younger set care about democracy? They did not suffer through the winter of 1918-1919 when the freedom of the German people hung in the balance. Now again constitutional values are in danger.” It can be deciphered that there was a serious disconnect between the youth and the elders; those who had experienced hardships due to the violent nature of their government, and the youth who was still new to grasping what it even meant to be part of the new democratic state. However, one must not disqualify the Germans as having no aptitude towards democracy since under the rule of Kaiser Wilhelm II, there were still democratic elections that were held at local levels in Germany.

One such argument that Hilden and Farquharson dismiss in Explaining Hitler’s Germany is that the link of national socialism to some mythical violent German character is absolutely unscholarly and achieved without any credible means of research. The notion that all the militarism in their German blood surged to their heads once Hitler had reoccupied the Rhineland descends to a level of National Socialist propaganda itself and greatly over-simplifies an answer. One of the most significant strategies that the NSDAP set forth was the attraction to be a stormtrooper for the SA and SS, and to be a member of the Hitler Youth during the depression years. Unemployed males were housed in dormitories and given free food and shelter in exchange for their full-time service as marchers and fighters for the cause. With the resurgence of the Nazi party during the onset of the Great Depression, hundreds of thousands of German youth flocked to enlist as stormtroopers for the Nazi party. At this point, the political scene had turned into a battlefield both in the hypothetical and concrete sense of the word. The militant veterans group, known as Stahlhelm, joined the Nazis in their street demonstrations against the crumbling republican system. The DNVP, another right-wing militant group, united with the NSDAP in the common cause to repeal the Young Plan of reparations and marched with Hitler’s men in synchronicity. The left gathered militant support as well and established their own political gangs. The Communist Red Frontfighters’ League fought for the proletarian dictatorship as well as against the socialist SPD, and the latter in turn fought back with the paramilitary organization known as the Reichsbanner. This realm of political chaos and economic uncertainty effectively lent the youth a reason to join one of the sides of the political establishment for protection and something to believe in during a time of seemingly endless crisis.

The final, and perhaps most crucial part in the nazification of the German people was the cold truth that once the Nazis had won the election of 1933, there was no further effort needed in converting the populace to their ideology. Once the Third Reich had come to power, public opinion ceased to continue. In a state where disobedience was punishable by death, all political conversation came to a halt, and this was exactly what the Nazis required in order to effectively wage the deadliest war the world had ever seen. Hilden and Farquharson note that, “terror was applied on a far greater scale once war broke out, especially when losing the war became a distinct possibility. Defeatism had to be overcome by all possible means. This is part of the explanation for the dramatic increase in the application of the death penalty from three categories of crime in 1933 to 46...” Additionally, ordinary courts lost power to the instruments of terror, particularly the SS and Gestapo. Concentration camp functionaries evaded any legal supervision with ease, SS officers ceased to provide any information on prisoners who had been ‘shot whilst escaping,’ and the so-called People’s court was supplanted by the SS and Gestapo. In a sense, the concept of fully nazifying and subordinating the German people to their ideology ultimately failed due to this fact. The use of terror was a confession of this failure. If the Nazis had truly rallied the German people to their cause, the terror would not have been necessary in the first place. Hitler knew he had lost the German people as the war lengthened and the prospect of defeat became increasingly more transparent, and with that knowledge he responded with brute force. The baiting and fighting for political votes was won on the basis of the manipulation of a beaten down, starving, and unemployed populace, suffering from the effects of the Treaty of Versailles and the Great Depression. A promise for the re-emergence of a greater Germany in cohesion with the reassurance of the Catholic Church and financial incentives consequently led the German people and their nation to ultimate destruction.

Bibliography

Allen, William Sheridan. The Nazi Seizure of Power; The Experience of a Single German Town,

1930-1935. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1965

Caplan, Jane. Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. "German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact", accessed March 09,

2016, http://www.britannica.com/event/German-Soviet-Nonaggression-Pact.

Hastings, Derek. Catholicism and the Roots of Nazism: Religious Identity and National

Socialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Hilden, John, and John E. Farquharson. Explaining Hitler's Germany: Historians and the Third

Reich. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble, 1983.

Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2008.

Merkl, Peter H. Making of a Stormtrooper. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Steinert, Marlis G. Hitlers Krieg Und Die Deutschen: Stummung Und Haltung Der Deutschen

Bevölkerung Im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Düsseldorf: Econ Verlag, 1970

https://steemit.com/israel/@socioecohistory/the-holocaust-6-million-lie-population-of-jews-1938-15-748-million-1948-15-753-million#@bitcoin1488/re-bitcoin1488-re-socioecohistory-the-holocaust-6-million-lie-population-of-jews-1938-15-748-million-1948-15-753-million-20170709t102031826z #sixmillionlie