WHAT IF EVERY BOOK HAD TO TEACH YOU TO READ? A Wish for the Popular Science Genre

What if the introduction to every book ever published was a complete education in how to read?

Imagine page one of literally every book on the planet: an illustration of an eye, an arrow leading into it, and a letter ‘A’ at the arrow’s butt. Start by seeing this letter is the message (change the letter as needed to fit your respective language).

Flip to page two, and see diagrams of human mouths, contorted into the shapes we make for each variation of the pronunciation of ‘a’, with wavy lines at the throat indicating use of voice: When you see this letter, it might mean these sounds with your throat and mouth…

…on to step three… and so on.

I can only guess that it would take a lifetime, at least, to teach a normal person to read that way. Imagine at age one hundred, just finishing your first pass on the introduction. You think “certainly, a refresher course is needed."

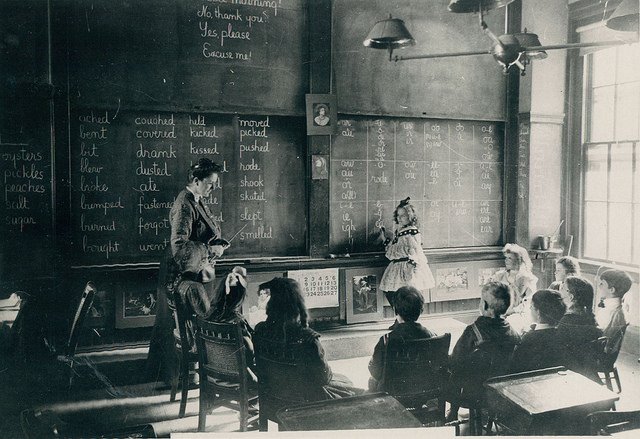

The seemingly infinite steps involved in moving from primitive conceptions of reading (the picture of the letter and the eye) into competent reading skills simply can’t be the job of Books. Rather, it is accomplished through massive collaborative efforts among many people within special institutions (schools). Books are written assuming a community of competent readers is out there already, and that baseline reading ability in any given community will be independent of any specific book or set of books, at least at the time of publication.

Yet there are books out there that task themselves—in an only somewhat metaphorical sense—with teaching the reader to read. It’s a type of book that you’ll probably recognize, one which is both (a) written for general audiences and (b) tasked with explaining highly complex concepts in the sciences—AKA Popular Science books. These books have no choice but to start from scratch, at least to a greater degree than is the case in other genres.

That’s because if you want to get non-scientists to really understand the science you’re writing about, you’ve got to spell out and explore even the philosophical foundations of science; the basics of statistics, and certainly the history of the topic your book is actually about—for starters. Whereas in a school system we can assume the reader/student has taken the prerequisite courses to grasp the texts they’re given, the more you make such an assumption as a writer of Popular Science, the less of a Popular Science book you have written. It’s a trade off. All argumentative writers are tasked with layering evidential, theoretical, and philosophical bedrock before they can get to the point, yet because so much of Science is rooted in principles that are utterly counterintuitive to normal human brains (Carey, 1986), this task is especially hard for Popular Science authors—hence the lengthiness of books in that genre, and hence PopSci not selling out in stores quite like your Harry Potters and Dan Browns. Let’s face it: the more complex the topic, the more a truly Popular book on the topic must resemble my imagined book that must first teach you to read.

Of course Popular Science writers assume some competencies in the reader (the ability to read, for example), but again, this limits their audience. Every science author (and their publishers, certainly) decides the cutoff for prerequisite competency for reading their book, and then works to teach the reader the “reading skills” necessary to get to the book’s point.

Personally, I enjoy a slim and elegant book. I often wish popular science writers would break with the time-honored tradition of laying down foundational concepts and topics and would just tell me, straight up, the basic guiding assumptions of the book I’m about to read and where I can read about them. Read the list, they’d instruct, and choose if you want to (1) go and learn about the fundamentals on your own time, (2) accept them as givens in the context of the book and read on, or (3) reject them flat-out and seek a refund for my book, (and maybe even send the author some hate-mail). This would be a book that spent the minimum time and effort on prerequisite assumptions, and so was only be about what it’s about. I dream of a book that gives the reader’s sophistication on all topics concerned the benefit of the doubt, by telling them exactly what the author needs them to believe in order for them to believe what the author wants them to believe.

References

Carey, S. (1986). Cognitive science and science education. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1123.

I think the first book I ever read was "Ant Picnic" or some shit in kindergarten. it pretty much when "there is an apple. there is a banana. there is a sandwich. there is a pie." story finished

I read the introduction or the first chapter and the last chapter of lots of books, enough to get the main idea and what is new in the author's treatment. In many cases, you're right -- that's enough.

Congratulations @deeallen! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCongratulations @deeallen! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

SteemitBoard World Cup Contest - The results, the winners and the prizes

Congratulations @deeallen! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!