The Roses of Sarajevo

There are 170 of them, scattered throughout the city of Sarajevo. Locals call them “roses,” but they are far from natural.

The “Roses of Sarajevo” are craters left from mortar explosions. As part of a project to commemorate the city’s four-year siege during the Yugoslav Wars, the craters have been filled in with red resin, giving them the appearance of spattered blood. The idea is that they force people walking to work or heading to a store to pause and remember the condition in which their city found itself not long ago, and to think at least briefly about the thousands of people who lost their lives during this incredibly difficult time.

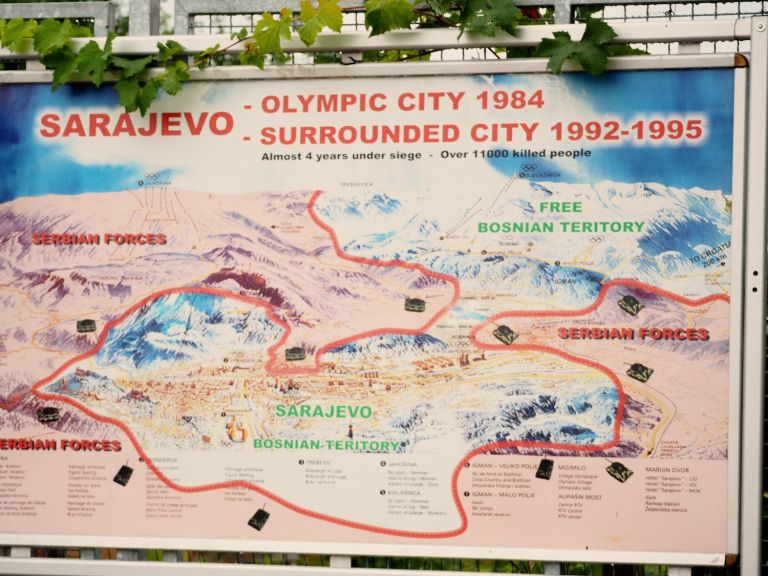

In 1984, Sarajevo was the host of the Winter Olympic Games. Just eight years later, Slobodan Milosevic’s Serbian Army laid siege to the city, cutting it off from the rest of the world for four years.

“Seige” is a word we tend to associate with Medieval battles and primitive warfare. Technically, a city is “under siege” when all routes in and out of it have been cut off, rendering impossible the flow of supplies and people. In this day and age, it also means that electricity, gas, and telecommunications resources have been interrupted, and that the city has been left in the dark, both literally and metaphorically. The objective of a siege is to force the city’s inhabitants to surrender to their enemy quickly. In the case of Sarajevo, that strategy didn’t work. Sarajevo held out for four brutal years during which residents lived in their basements while shelling, sniper fire, and routine bombings occurred above and around them.

The origins of the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990’s go way back, as the seeds of conflict often do. Some people ascribe responsibility for the war to centuries-old ethnic infighting amongst the various Balkan states, and to be sure, ancient resentments undoubtedly played role. However, most local people say that Bosnians, Serbs, and Croats (ethnic Muslims, Orthodox Christians, and Roman Catholics, respectively) were living side by side in relative peace throughout the former Yugoslavian territory until shortly before the crisis. What seems clear is that divisions were created in the last couple of hundred years when some sections of the Balkans were made a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and others part of the Ottoman Empire. World Wars I and II exacerbated these divisions, as different groups within the greater Balkan area were pitted against one another as a result of alliances with opposing empires. The country of Yugoslavia had been created just after WWI and functioned relatively well for twenty-seven years under an authoritarian leader (often referred to as a “benevolent dictator”), Josep Broz Tito. After Tito’s death in 1980 and the collapse of communism in the former Soviet Union, the young country started to suffer economically. The discontented feeling of having been pawns of larger nation-states for far too long rankled in the minds of all Balkan people. As commonly happens in eras of hardship, infighting increased, and simmering nationalistic sentiments related to “regaining their former glory” bubbled up to this surface within a number of the Balkan ethnic communities. This explosive combination set the stage for a deranged charismatic leader’s ascent in Germany just fifty years prior to the Yugoslav Wars; unfortunately, history repeated itself in the Balkans in the form of Slobodan Milosevic.

Slobodan Milosevic, leader of Yugoslavia’s Communist Party, seized the presidency in 1990 and brought with him a vision of a “Greater Serbia,” a united Serbian and Orthodox Christian state that would reclaim its historic glory and create economic opportunities for its racially and ethically pure citizens. Once in the power seat, he replaced various governmental officials with his own allies and forced through the government a number of measures that were unacceptable to the Slovenians, Croatians, and Bosnians in the northern (and less ethnically Serbian) parts of the country. Slovenia and Croatia walked out, beginning the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Meanwhile, Milosevic had been working towards empowering his vision by slowly purging the national army of Muslims, Catholics, and Jews, so that when he was ready to mobilize the Serbs against other former Yugoslavian states he had the full loyalty of his army and control of the majority of the former nation’s firepower. At the same time, he and his colleagues produced propaganda campaigns that exploited the existing religious and ethnic differences in the former Yugoslavian states and played upon citizens’ financial insecurities. These campaigns were frighteningly effective, and resulted in far too many cases of neighbors turning on neighbors. Much is uncertain about the numbers of Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians that were killed in the war; depending on which side is presenting information, you’ll encounter different statistics. What is certain is that Milosevic fomented hatred in the Balkans, created and sanctioned concentration camps, and promoted and conducted ethnic cleansing campaigns, making him responsible for countless deaths. He died in his cell in 2006 before his five-year long war crimes trial was concluded.

Bosnia and Herzegovina tried to appease Milosevic for as long as they could, knowing that if the war came to them it would be bloody. They reached their breaking point in March of 1992 when they seceded from Yugoslavia – without the support of the Bosnian Serb community, beginning the Bosnian War.

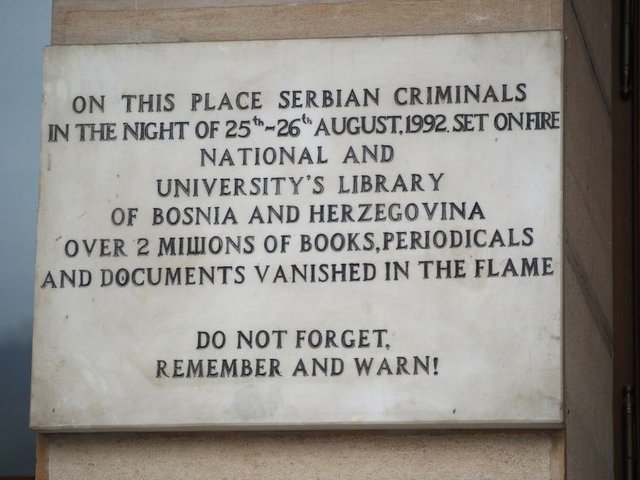

At the outset of the war, the majority of Sarajevo’s population was ethnically Muslim (with many being non-practicing Muslims whose ancestors had converted to Islam during Ottoman rule in order to have access to better jobs which required that their holders be Muslims) with a strong Catholic minority. These two ethnic groups were concentrated in the flat center of the city, while the Serbs occupied the hills above and surrounding it. Milosevic had romped through and conquered Slovenia in ten days and was planning to have a similar decisive conquest of Bosnia and its ample natural resources when the Serbian army laid siege to Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, in April of 1992. They fired on the city below from their strategically advantageous locations in the surrounding mountains, and over the next four years, Sarajevo experienced and average of 300 shell impacts per day, with much of the destruction aimed at governmental buildings, medical facilities, and centers of media and telecommunications.

Siege darkened the city, literally and figuratively. Without power, residents were unable to light their homes. Without electric or gas heat, they were forced to cut down and burn the city’s trees, and the results of this can be seen on Sarajevo’s main thoroughfare, called “Sniper Alley.” Where there are mature trees still lining the road, the area was too unsafe to cut down trees during the conflict. Where new young trees are planted now, mature trees were cut and burned during the siege – meaning the area was safe enough that someone could be out there cutting for the time it took to harvest the wood. Residents of the city spent most of their time underground, coming to the surface only long enough to race to a relative’s home for a visit, or to stand in line for the limited food aid. Milosevic’s army repeatedly dropped bombs on these food lines, knowing their results would be devastating. As a result, the majority of Sarajevo’s “roses” are located where aid lines once were

Sarajevo’s residents found a way around the siege, however. In an impressive show of resourcefulness and resilience, they constructed a tunnel allowing for the delivery of goods and ammunition – an achievement I’ll discuss in another post, along with the conclusion of the siege.

It’s this resourcefulness and resilience that the “roses” celebrate, even as they simultaneously remind everyone of their sadness and the loss of close to 11,000 citizens. There are bullet holes in walls nearly everywhere in this city; they call up visions of snipers hiding and bombs dropping. The roses, on the other hand, conjure up images of people risking their lives to stand in line for food they could bring back to their basements for family and friends – an activity they risked their lives for throughout four long years of siege.

That’s a worthy, albeit painful memory.

Bok @vekoni pridruži nam se na novo podignutom Balkan Steemit Alliance discord serveru za balkanske Steemit korisnike detaljnije o ideji možeš pročitati u linku ispod

https://steemit.com/steemit/@ivan.atman/official-balkan-discord-server-is-up-and-balkan-steemit-alliance-is-up-steemit-balkan-savez-sbs

(server je tek podignut i možda budeš među prvima na praznom serveru, međutim svi su obaviješteni te će stići uskoro)