Pilgrim Tales #5 - The Secret Community Of Pilgrims Who Lived At World’s End

I’m an adventurer, thrill seeker, and life enthusiast with a shorter life expectancy than your mother’s cat - Follow my never-ending journey.

Pilgrim Tales - is a series of posts on my journey along The Way of St. James. An 800 kilometre trek across the North of Spain. Read about the adventure, the mishaps, and the strange yet inspiring characters I met along the way.

This is the story of how I lived at World's End.

While walking across Spain, I repeatedly came across whispers of a secret community of pilgrims living at the so called End of the World.

According to rumour, this community was hidden in a forest by the sea in the coastal town of Finisterre.

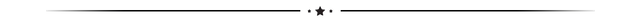

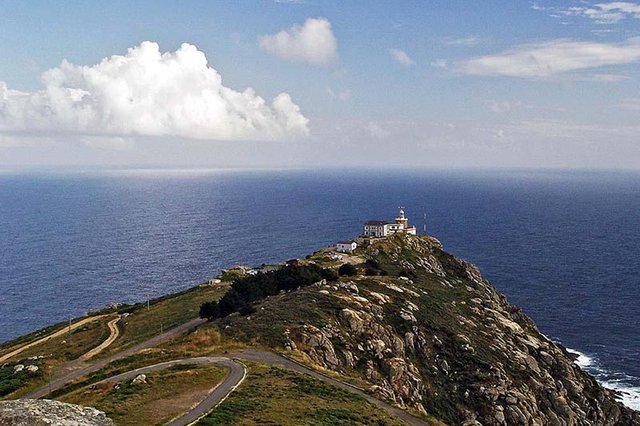

The village is a four day trek from Santiago, and many consider this to be the true end of the Camino. It’s known as the end of the world because Finisterre in Latin is Finis Terrae; end of the earth.

In Roman times this location was in fact the end of the known world.

Supposedly, the pilgrims in this community didn’t want their pilgrimage to end, and so they stayed at the end of the world in a perpetual state of limbo.

Naturally, I was intrigued. I didn’t want my pilgrimage to end either, and I imagined this community to be filled with kindred spirits.

There was no question; I had to find these people.

Together with Rebecca— an Australian woman I had met during my pilgrimage— I traveled to Finisterre. For two days we asked around town if anyone had heard of a band of pilgrims living at World’s End, but nobody had.

Perhaps the community had existed at some point, but it seemed that by the time we got there it was long gone.

Or so we thought…

A few days later, a group of travelers entered our hostel. They were pilgrims, like us, but something was off about them. We quickly discovered they had been living at a camp deep inside the woods for over a month.

They said the atmosphere inside the community had turned toxic, and so they decided to leave. Apparently, the founder— Frederique— had exploited them for money, food, and labour.

Regardless of this new information, I asked the escapees for directions.

Follow the beach until you come across a small creek flowing inland. follow the creek until you reach the rocks. From there, look for a small hidden trail quite a piece up. Follow the trail; it will lead you directly to the camp.

Later that day..

Rebecca and I found the dried up creek. We followed it up the rocks, and found the hidden trail. My face was fixed in a permanent grin, excited that we might find the elusive band of pilgrims. We followed the trail as it led into the woods, but then abruptly stopped. A huge wall of bush towered over our heads.

It was a dead end.

That’s when we heard the voices. We saw movement through the greenery, and realised the wall was wasn’t a dead end at all, it was artificially constructed. We worked our way through, and stumbled into the camp. A young man, with long and messy black hair smiled at us.

Welcome. You found us.

This was Frederique. He spoke with a strong French accent, had severely discoloured teeth— of which several were missing— and wore tattered clothes that clearly hadn’t been washed in awhile.

Frederique had walked the Camino over two years ago. When he reached Finisterre he didn’t want his journey to end so he pitched a tent on the beach.

In time other pilgrims joined him, until locals complained about the beach bums and they were forced to settle in the woods.

He ran out of money a long time ago, and explained that he depended on pilgrims for food, water and help around camp. So far he’d survived two winters, and slowly built up the camp to what it was now.

The camp was roughly the size of a basketball court, though more roundish in shape. Frederique’s shelter looked like an unfinished Mongolian yurt. The support structure— entirely made up of branches— was mostly bare.

Large logs lay around a giant fire pit, and throughout the encampment old tarps functioned as primitive shelters. At the far end of camp a wooden sheet rested on top of tree trunks.

Scores of cups, cans, jars and sauce pans were scattered on top. The jars contained everything from twine, nuts, and bolts, to handcrafted stakes, paper snippets, and tinder.

Next to the makeshift table dozens of spiritual books found their final resting place on a crude and crooked bookshelf.

And lastly, a buddhist shrine was built into a small rock cavity. Sheltered by naturally formed arches, and covered with pillows, the space functioned as a tiny meditation area.

The camp felt oddly deserted. The only other person there was a blonde teenager named Mikey. He wore army fatigues, and was quite muscular. He completely ignored us, and continued to pile heavy rocks at the edge of camp.

Frederique offered us coffee, which I graciously accepted, and Rebecca wisely declined. He brewed it in a rusty saucepan on top of a faulty camp stove, and poured it into a filthy, cracked mug.

The taste of it can only be described as lukewarm kerosene. At this point I’d like to remind you that I’m the guy who heats coffee in a microwave; I’m not picky. However, the only resemblance this concoction had to coffee was that it was wet, brown, and obeyed the laws of physics.

Frederique told us about his struggle to make his camp winter proof. According to him a few weeks back the camp was alive and bustling with pilgrims, but since the temperatures dropped most of them had left. Frederique repeatedly invited us to stay and help. Clearly lots of work still needed to be done, and he lacked the manpower.

To make matters worse; Frederique had a huge lump on his elbow, and as a result his arm was permanently fixed at a 90 degree angle. He’d injured himself several weeks earlier, but without health insurance or money couldn’t get it fixed. I didn’t particularly like Frederique and my gut instinct told me something was off. However, intrigued by the idea of living at the end of the world, I decided to stay.

Rebecca and I parted ways at the bus station in Finisterre, but as soon the bus drove off, I wondered if I should have gotten on that bus too.

I shook off the thought, shifted my focus, and returned to the camp.

A few days later Mikey and I were collecting rocks. He struck me as a lone wolf. He made no efforts to start a conversation, never used more words than necessary, and seemed genuinely uninterested in other people.

After several days I managed to peel off several layers of the onion. I learnt he was 20 years old, grew up in England, and moved to Finisterre with his parents in 2008. His short temper and violent outbursts made it hard for him to fit in at home, and so he spent most of his time here in the woods.

As time passed more pilgrims appeared, until our community had grown to about a dozen people. One day all of us went on a trek to the lighthouse at the very edge of Spain.

The lighthouse was built on a collection of giant rocks called Costa da Morte— The coast of death— named after it’s rough and jagged nature, which poses serious threat to marine vessels in the area.

The sun was setting as we climbed down and joined other pilgrims around a small fire between the rocks.

Camino lore dictates you symbolically burn a piece of clothing, marking the end or death of your pilgrimage, and the start of a new life. I had the brilliant idea to burn one of my socks.

However, once on fire, the hidden aroma’s of 800 kilometres of suffering were released into the atmosphere. The smell was so intense I think not even Dobby the house elf would have accepted that sock.

Being outside of normal society meant we were oblivious to the pressures of time. We spent our days prepping camp, and our evenings around the fire with food, wine, and guitar music.

It no longer mattered what day of the week it was. We simply exsisted, and somehow always had something to eat. It was a wonderful time. Staying with the pilgrims at World’s End made it possible for the joy and comradery of the Camino to linger on just a little longer.

That is, until one day our little paradise turned out to be less than perfect.

At first I thought I’d found a unique community of leftover pilgrims. A rag tag group of travellers from around the world whose lives were only limited by their own imagination.

However, over time cracks appeared in that rosy picture, and I started to understand why all the other pilgrims had left. We lived in a forest at world’s end, but the more I got to know Mikey and Frederique, the more I noticed the bubble in which they lived.

It seemed everyone who didn’t agree with their way of life was a money-grubbing, scrooge-like materialist. Ironically, since I did have money, Frederique gradually asked me to buy more and more stuff for him.

Often Frederique used his elbow injury as an excuse to do nothing except sit on his pillows and tell all of us what to do. He often talked about meditation, breath awareness, and the calmness of life without money, but it seemed his version of mindful breathing mostly involved smoking himself into stillness.

One day I concluded I didn’t want to be there anymore, and so I packed up my stuff, said my goodbyes, and left.

It was time to move on.

And so my pilgrim journey had truly come to an end.

1.60% @pushup from @thisishowidie