The Danube's Embrace (featuring Vasily Peskov as author)

I was travelling by train and, as usual, got to talking with my travelling companions.

"There wasn't a drop of water in Kishinev in 1944. The city changed hands several times during the war. The waterworks were destroyed, and there literally wasn't a drop of water in the entire city! Then someone remembered a little spring in an old orchard known as Boyukany. People stood in line for water there with pails, pitchers and glasses."

"Well, we're surrounded by water. We can't escape it. We spend our whole lives on the water. There was even a cover story about us in a magazine. That's what it said: They live their lives on the river.' Vilkovo's in the mouth of the Danube, right before it reaches the Black Sea."

I jotted a note in my pad: "Vilkovo. Waterways instead of roads. Fishermen. Old Believers. Danube herring."

I now had a chance to visit this "Little Venice".

It was not difficult to find my way from Kishinev. You take the small steamer at Izmail and sail down the Danube to the Black Sea. If time is of the essence, go by Raketa, a hydrofoil passenger boat. This sparkling white missile trembles as impatiently as a hot-blooded steed. When the captain finally lets go of the reins, the Raketa zooms off like a rocket should, though there is no exhaust, just billowing white spray in its wake. Anyone whose first ride this is will exchange amazed glances with the other passengers. Perhaps one might go up on deck? Never in your life! You'd be blown right off the boat.

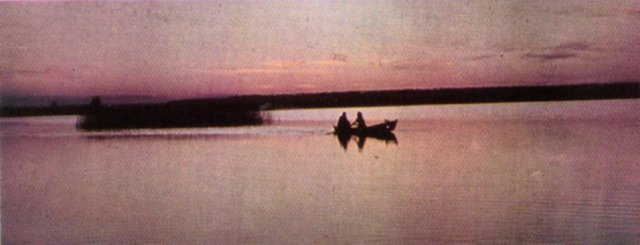

The left and right banks are much the same. Both are studded with topless old willows. To the left is the Soviet bank, to the right the Romanian bank. Both are marked by border posts. Two fishermen are fishing, one near the right bank, the other near the left. A border district has its own laws. One is not supposed to speak across the border, but I'm sure these two fishermen talk to each other. Perhaps they say: "Any luck?" "No. You know what it's like in autumn. They don't bite."

The sign on the pier read "Vilkovo". There was a crowd of people come to see a group of young fishermen off to the army. The recruits seemed set on pounding the decking to bits with their heels as they danced to an accordion, which gave out every bit of air there was in its bellows, heaving mightily through its brass nostrils. A kerchief in a dancer's hand weaved in and out. An old woman wept. Two girls giggled as they sprinkled petals on the boys' heads. Several songs were going at once to add to the general confusion.

"All right, everybody! We're pulling up the gangplank!" the captain called and mounted the bridge. The Raketa flashed its white tail, carrying the accordion and the young boys off along the Danube.

The pier became deserted. Aster petals and a crumpled cigarette wrapper floated on the surface.

Two small boys noticed my camera and telephoto lens. A few minutes later we were friends, attracted to each other by our mutual questions that sought to be answered. I was asked whether I would let them carry my leather case and camera and tell them about Moscow. I, in turn, asked them whether they'd show me around Vilkovo.

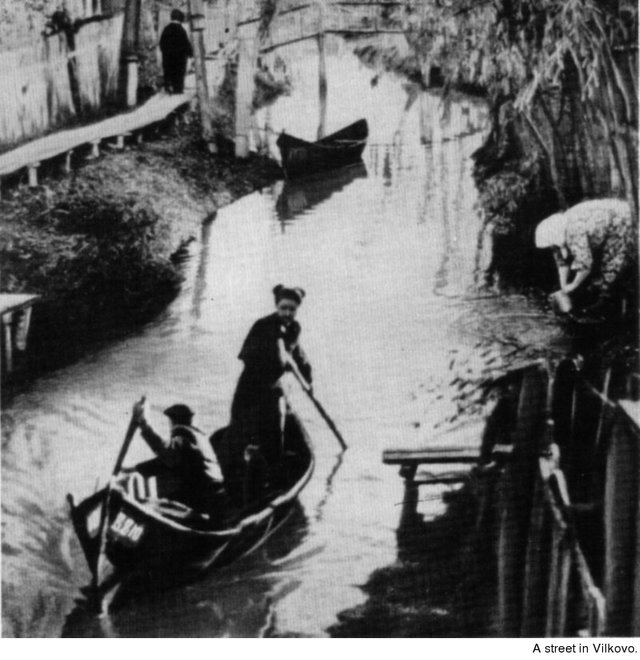

Vilkovo is a wonder. The houses and front gardens are all aligned, as anywheres else. Crocks were drying in the sun and wash hung from the lines. But the only way you could go down a street in this town was in a boat. Water coursed down every street and lane, with no sign of pavements, cobblestones, or even plain simple grass, as on any other village street. The houses are built just slightly above the water. There were grapes, apples and pears growing on the vines and trees beside the houses. When an apple ripened and fell to the ground, but no, there was no ground beneath the branch, it would fall with a plop into the water and float away. If you feel like fishing here you take your net and fish in the street. If you feel like swimming, you can even dive out of the window. Or you can cast your line through the window. The fish come fresh to the frying pan here. The silt of the narrow banks and front gardens is so fertile that anything will grow in Vilkovo. If they stick poles into the water at the edge of a canal the poles sprout leaves. Soon a new fence has turned into a row of blossoming broom. Rowboats are a vital necessity. When a child is born it is brought home from the hospital in a rowboat. A couple getting married sets out in a boat. If someone has bought a bed or a table it is also delivered by boat. And when a person dies he starts out on his last journey by water, too.

If the tide is low you can walk along the wooden sidewalks that are built on piles the length of the canals, some half a meter wide, others only as wide as a single plank. A stranger might topple over into the water in the dark, but the local people are sure-footed. You can tell who is passing at night by the sound of his steps: if the boards creak and groan it means a tipsy fisherman in hip-boots is stumbling home. High heels clicking mean a girl is hurrying to meet her date. And that sounds like a barrel of fish being rolled along the walk.

All the sidewalks and canals lead to the main canal. Two thousand boats are tied up here each night! The rowboats are called kayuks, and they resemble Indian canoes. The sides are deep and the bow is sharply curved. Many have outboard motors for the river or for sailing along the seacoast. It's against the law to run a motor on the streets. Violators are stopped, and if they try to get away their number is taken down, for every boat has a license, just like a car. However, out on the river the boats take over. There are the kayuks; the next larger size are called moguns, and the big boats are called felugs, while the seiners are in a class with regular ships. This great flotilla lies in wait for the Danube's fish, which is abundant and of excellent quality. For one, there is the Danube herring, truly a delicacy. There are also sturgeon, beluga, bream, pike, perch, carp, sheatfish and tench.

I asked the boys to take me to see the most famous fisherman. Vanya and Petya went into a conference.

"There's Yakov Ungarov... And Volodya Ungarov, and Kondrat Sevizin, and Kuprian Izotov..."

"You know," Petya said, "even though old Grandpa Makhno isn't on the board of honor, he's the head fisherman all the same."

We set out in search of Grandpa Makhno.

The old man was keeping watch over the nets. His real name is Feodosi Ovsyannikov, but he's been known as Grandpa Makhno for so long that he'll raise an eyebrow if anyone calls him by his given name.

"I'm seventy-seven. Spent nearly seventy years fishing. I've had all kinds of catches. What? Beluga? No, they weren't fooling you. I had one this big. It was bigger than me and weighed forty poods!" He brightened, saddled the bench and went on with his story. We never doubted that the fish was bigger than he. "This is the first year I haven't gone out when the fish are running. Here I am, watching the nets instead. Just think of it, young fellow, here I am, sitting around, watching the nets. If you want to know about the fish this season, ask Volodya Ungarov, he's one of the best."

However, the young skipper and his crew were out near Kerch, fishing for khamsa, a small fish common in the Black Sea.

Vilkovo is a small town. Petya Izotov and Vanya Karasev showed me all they could in a day. I suddenly noticed that Petya had gone out in his father's felt slippers. They were obviously ill-suited for our journey, but he did not want to go home and change and so had taken them off and was carrying one slipper in each hand, stomping barefoot along the planks, his feet as red as a gander's.

We saw some people unloading sheaves of cattails near their houses (kindling for their stoves in winter). Another boat was piled high with carrots (their garden crop for the winter). A young and apparently visiting priest was standing in a third boat, gripping his stylish leather suitcase. He had a popular magazine under his arm. A bearded old man was rowing him to the church which towered over the settlement like a beacon.

"Were you ever up in the belfry, boys?"

They had not been, so we decided to climb up and have a look at Vilkovo from on high.

We had to have the permission of the church warden to climb the belfry. Saturday Mass was in progress. After making our way around inside the stuffy church which smelled of sweat, wax and incense, we found the warden. The old man had a bluish-gray beard. He wanted to know who I was and where I was from and then finally unlocked the door leading to the narrow staircase.

It is an old and simple structure, built soon after the settlement was founded early in the 19th century. There were no more than ten families in the beginning. They were all Old Believers, a fanatically religious sect of strong, hardworking people. They wrenched a strip of land away from the Danube, built their houses on embankments and planted orchards, and their roots went so deep that the settlement flourished. It now has ten thousand inhabitants.

The view from the belfry was most unusual: there were the silvery ribbons of the canals, the waterway streets between them, the houses on their little islands, clusters of boats and, farther on, water, reeds and willows.

All this water has passed through Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Romania and now glitters and laps at the houses of the Russian settlement of Vilkovo. In some regions the Danube serves as a borderline, but it is also a waterway that brings people together. Everywhere along its length fishermen hopefully await each new sunrise, rejoicing if their hopes are realized and grieving if the catch is small.

The lettering on the churchbell reads: "Donated by the merchant Semyakin and his sons." We slapped our hands against the bronze, sending a dull sound down in waves, so that it seemed this sound and not the wind caused the ripples on the water.

"Look at all that water!" Petya said. "I could take a boat and just go off, far, far away..." It was not as if a child were speaking.

The stairs creaked. It was the old warden. He informed us politely that it was time for him to lock up.

Once again we watched the boats on the streets. Some were carrying yellow cattails or sacks of potatoes. Two bearded goats stood calmly in another, and the same priest gripping his leather suitcase was being rowed back to the pier.

excellent story congratulations, thanks for sharing beautiful places