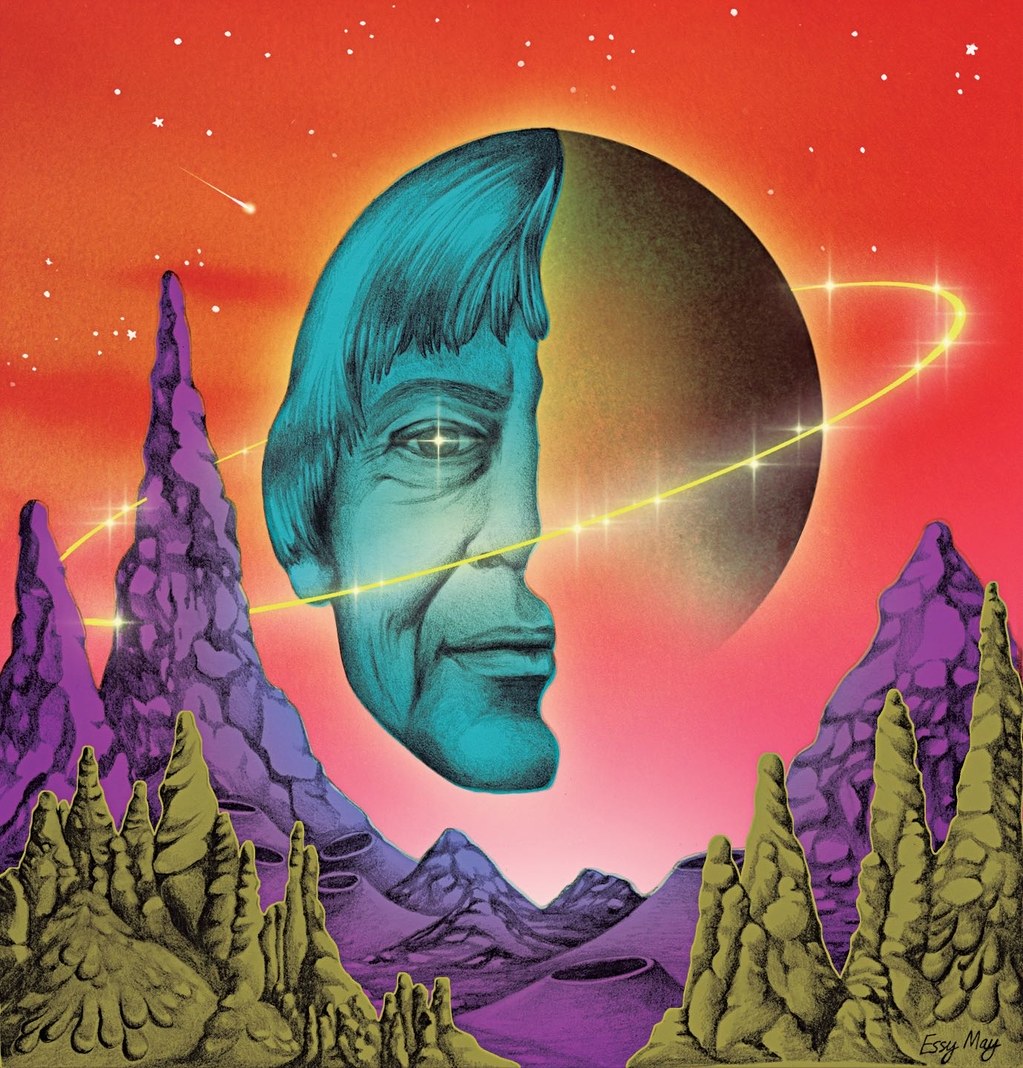

The Fantastic Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula’s mother was Theodora Kracaw Kroeber, born in Denver in 1897 and raised in the mining town of Telluride. A friend of Le Guin’s recalls seeing her, at the house in Berkeley, “coming down the long staircase, a majestic-looking woman with a long gown and a great big Indian silver and turquoise necklace. She was very stately.” Theodora took to writing in her late fifties, and produced “Ishi in Two Worlds,” a nonfiction account of the last survivor of the Yahi people. Le Guin loved her mother and admired her psychological gifts. But she says that their relationship also contained “something darker and stranger” that she has never quite understood. “We were very lucky, because we never had to act that out. But if I see daughters and mothers act it out toward each other it doesn’t shock me or surprise me. It’s there.”

The Kroeber household was full of voices as well as stories. Alfred liked to pose philosophical questions or puzzles over the dinner table and ask his four children about anything that interested them. The kids were encouraged to take an active part in the conversation, but, as the little sister, Ursula rarely got a word in: “There were too many people, and I was outshouted by everybody else.” Learning how to be heard taught her persistence and gave her a tendency to appear fiercer than she is. “People think I mean everything I say and am full of conviction, often, when I’m actually just floating balloons and ready for a discussion or argument or further pursuit of the subject. It’s my fault—I speak so passionately. Probably because, as the youngest and shrillest child of an extraordinarily articulate and passionate family, I could only be heard by charging over the top, shouting, ‘Marchons, marchons! Qu’un sang impur abreuve nos sillons!’ every time I entertained a passing opinion.”

Le Guin’s work combines a Berkeleyite’s love of alternative thought with a strong scientific bent that she sees as an inheritance from her father. In her fiction, she has tried to balance the analytical and the intuitive. “Both directions strike me as becoming more and more sterile the farther you follow them,” she says. “It’s when they can combine that you get something fertile and living and leading forward. Mysticism—which is a word my father held in contempt, basically—and scientific factualism, need for evidence, and so on . . . I do try to juggle them, quite consciously.”

If it was difficult to be the youngest and most precocious of the Kroeber children, leaving the house to enter the world made Ursula feel like “an exile in a Siberia of adolescent social mores.” In the fall of 1944, at fourteen, small for her age, disguised in the sweater, skirt, and loafers of a “bobby-soxer” (a term that still makes her shudder), she began her first year at Berkeley High School, a huge, impersonal institution where popularity mattered more than learning, and fitting in was the ideal. When Le Guin speaks of her teen-age years, she speaks of loneliness, confusion, and the pain of being among people who have no use for one’s gifts. “You’re just dropped into this dreadful place, and there are no explanations why and no directions what to do.”

She found a refuge in the public library, reading Austen and the Brontës, Turgenev and Shelley. In fiction, she could satisfy her deep romantic streak: she fell in love with Prince Andrei in “War and Peace” and once, at thirteen, defaced a library book by cutting out a still of Laurence Olivier’s Mr. Darcy and taking it home to look at in private, guilty rapture. From Thomas Hardy she learned to handle strong feelings in fiction by pouring them into landscapes, letting the settings carry part of the emotional charge. “There’s a patronizing word for that: the ‘pathetic fallacy,’ ” she says. “It’s not a fallacy; it’s art.”

As a child, she was painfully shy, and she still alludes to anxieties that she keeps hidden from the world. I caught a glimpse of that when she asked me, cautiously, “Wouldn’t you say that anybody who thought as much about balance as I do in my work probably felt some threat to their balance?” After a long pause, she added, “Of course all adolescents are out of balance, and very aware of it. To become adult can certainly feel like walking a high wire, can’t it? If my foot slips, I’m gone. I’m dead.”

“With the money we’ll save by shutting down quality control, we can issue some truly spectacular apologies.”