Bonnie Brereton: finding democracy in Thai Buddhist murals

Old temple murals, known as hup taem in Lao, are going through a cultural renaissance in the Northeast, after decades of being neglected and demolished in favor of Bangkok-style murals. Dating back to the early twentieth century, murals on the walls of ordination halls, or sim, depict popular stories like the life of the Buddha, Vessantara Jataka, and religious imageries like heaven and hell. They also feature local landscapes and everyday activities like farming in a uniquely vernacular style.

This form of people’s art is only now beginning to be recognized, both locally and nationally. The Tourism Authority of Thailand is finally promoting visiting sim – and not just bat caves and snake farms in central Isaan, as it has done for many years. In 2015, a nonfiction book tracing the Lao epic Sang Sinxay on murals in Isaan won a national prize.

This past August, a seminar in Khon Kaen, organized by the Faculty of Fine Arts of Khon Kaen University (KKU) and the Isan Writers Association, brought together experts on literature, visual arts, and community development, to explore and discuss hup taem on both sides of the Mekong. Several Laotian experts participated in the seminar as well.

One of the presenters was Dr. Bonnie Pacala Brereton, an American art historian and Buddhist studies scholar who specializes in vernacular forms of cultural expression in Isaan and the North.

Since 2004 she has been a researcher at the Center for Research on Plurality in the Mekong Region, Khon Kaen University. Along with Somroay Yencheuy, she is a co-author of a 2010 book Buddhist Murals of Northeast Thailand: Reflections of the Isan Heartland. An earlier book, Thai Tellings of Phra Malai, (1995) was a study of the different regional versions of the Phra Malai story.

In this interview Brereton talks about her interpretation of the murals as a “democratic vision of society,” and the growing recognition of the shared culture in a region stretching from central Isaan to Laos.

Interview by Peera Songkünnatham

Could you elaborate more on your view that hup taem show a democratic vision of society?

Hup taem are located in villages, where there was probably relatively little social stratification. I would imagine that the most highly respected people were monks, former monks, and elderly people in general.

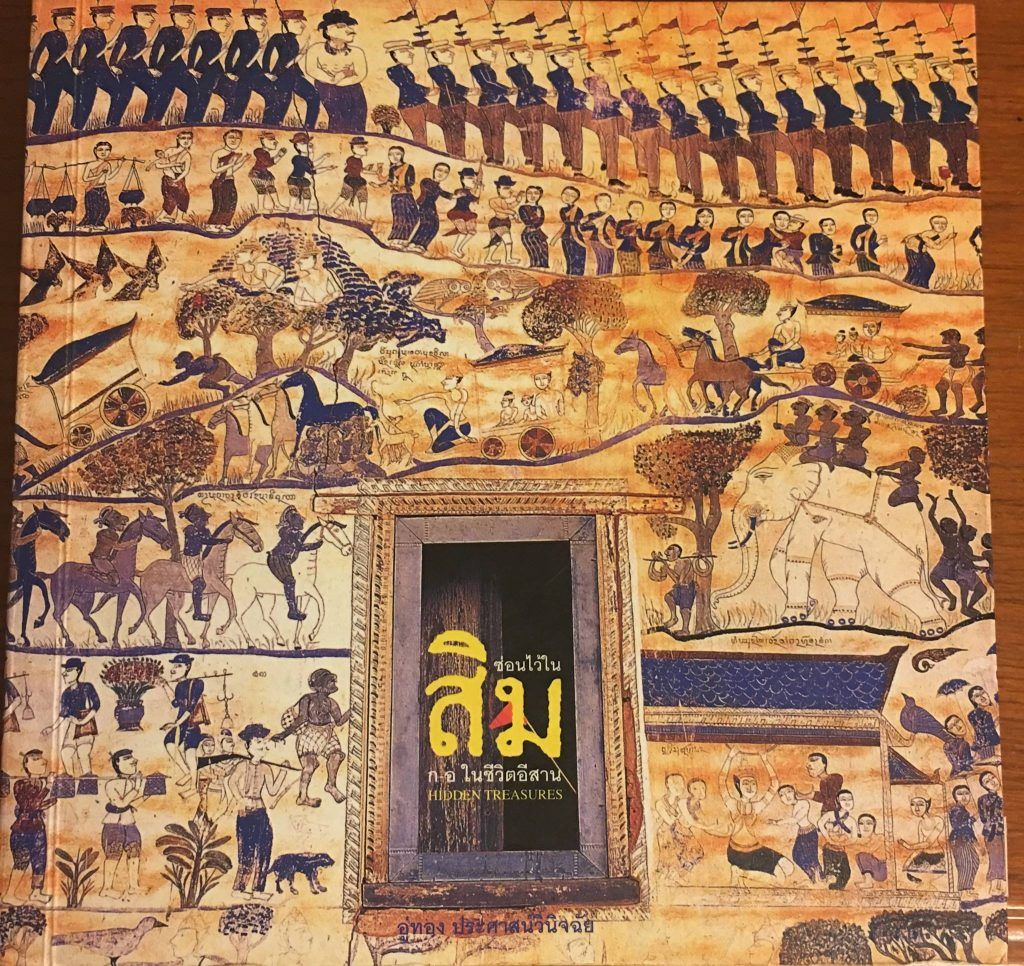

Notice the composition in this photo [above], which is on a book cover. The top register consists of soldiers but they do not look like Thai soldiers, especially those of today. The register below the top has women and men in procession as in bun phra wet [an annual merit-making festival in Isaan villages], and then below are several registers of some scenes from the Vessantara Jataka [the last story of the Buddha’s past lives]. On the left of the bottom register is another scene from this story with the Brahmin Chuchok taking away Vessantara’s children, and on the right is a childbirth scene from the Lao version of the Rama epic.

The point is that the movement is horizontal and that the top of the mural is not reserved for high-status characters and the low for “kak” (the dregs of society). This is very different from Central region murals, where deities and kings are at the top and powerless people at the bottom.

With relatively little social stratification, the traditional Isaan village still had a preferential respect along gender (female<male<monks) and age lines. Would you say that the murals’ “democratic vision of society” an aspiration for even less social stratification?

We know so little about the history of society in Isaan, but it seems to me that village society probably did not have a rigid hierarchy and that it was relatively democratic, or rather egalitarian. But I don’t think people would have objected to treating elders and monks with more respect as they held society together.

As for aspirations for less social stratification, I think this is a modern phenomenon and that people with little power are smart enough not to openly express what they can’t attain.

In your presentation, you expressed distaste for the term kak used to describe marginal figures in Thai murals. Would you say that kak as an analytical term has no place in describing Isaan murals?

In Central Thai murals, “kak” or “the dregs” refers to common people, often depicted as country bumpkins, at the bottom or doorways or corners. As far as I have noticed, there are no kak in the hup taem of what I call the Isan Heartland.

The continued use of this term amazes me. As far as I can tell, no one has questioned its acceptability in the twenty-first century, but I guess this reflects the great social stratification that still exists in Thai society. It seems acceptable as a term from the past that some people still find useful when identifying figures of common people, as long as it’s used in the context of how the painter saw these people. But I prefer the term “genre scene,” which is used in the West to refer to scenes showing the everyday life of ordinary people.

You also chose to call hup taem “people’s art” rather than “folk art”— what is the significance to this word choice?

Regarding “folk art,” versus “people’s art,” the former has many meanings, some of which seem condescending, while “people’s art” seems more neutral, and more accurate. It’s the art of the local people and they are often included in it, for example , in murals of the Vessantara Jataka processions.

In her keynote speech, scholar of Thai arts and literature Dr. Sukanya Phattharachai admitted that her first impression of hup taem was that they resembled “kids’ drawings.” Did “kids’ drawings” occur to you as well upon first seeing hup taem in 1989?

It never occurred to me to think of them as kids’ drawings. I was amazed at the diversity of compositions, the complexity of many of them and the use of space.

They do vary in quality from one temple to another, of course, and at some temples it appears that more than one artist or craftsman with differing skills did the painting. Those at Wat Sa Bua Kaew [in Nong Song Hong district, Khon Kaen] are much more highly skilled than those at Wat Sanuan Wari [in Ban Phai District, Khon Kaen], for example.

It seems to me that Isaan/Lao cultural forms, in general, are amazingly complex – music, for example, khaen chords and rhythm and the intertwining of the sounds of a musical ensemble, consisting of khaen, phin, drums, etc., and voices. Weaving is also complex beyond words – both the patterns and the looms, which vary from one ethnic group to another.

But to answer your question, I think that to say that hup taem resemble kids’ drawings implies that they are inferior and I don’t agree.

How does the social vision portrayed in hup taem correspond to real life?

This can be seen quite clearly in pha phra wet [the long Vessantara Jataka scrolls] especially in paintings representing Nakhon, the final chapter of the Vessantara Jataka, where Phra Wet returns to the city and is accompanied or welcomed by the townspeople, who look very much as if they are participating in a Bun Phra Wet procession. They’re having a good time – dancing, often flirting, drinking.

You titled your talk “murals in motion,” drawing attention to movement in the paintings as well as the scrolls paraded by locals in the annual bun phra wet festival. Is motion a particularly unique component of Isaan hup taem compared to murals in other places?

If we look at the murals of Thailand’s central and southern regions, the scenes there are lodged in place – in a certain setting, such as a forest or a palace, and they are often contained in a frame, sometimes demarcated by palace walls and the people are lodged in place, often in a pose. But even if they are walking or marching, they don’t go very far, because they are enclosed in that frame.

Hup taem, however, usually consist of many registers – or layers – one on top of another, with lines of figures moving all the way from one end of the wall to the other, as in the mural above.

Another example of the absence of social stratification in Isaan murals can be seen at Wat Photaram in Maha Sarakham [see above], in a scene from the life of the Buddha. Notice that at the bottom of the mural, the future Buddha is leaving the palace as well as his concubines and newborn son. And right outside the palace wall – not below it – are farmers plowing a rice field. Notice also the energy in the farmers – one is almost running.

Do you see any connections between the motion and energy present in hup taem and actual mobilities and movements of Isaan people?

There are several, both literary and historical. The most common stories in hup taem pre-2500 B.E. [1957] – the Vessantara Jataka, Phra Lak Phra Ram, and Sinxay – all involve a long journey by the main characters, usually because of exile and into the forest, where they encounter hardship and sometimes adventure, followed in the end by a grand procession back to the royal city.

In terms of local history, countless numbers of people were brought as war slaves when Vientiane was sacked [in 1828] and Chao Anouvong [last king of Vientiane] was captured and taken to Bangkok. But all I know is that they were taken to a lot of different places in Isaan and the Central region.

And there is the also the tradition of forest monks, most of them from Isaan, who walked as part of their meditation practice.

It also seems to me that Isaan people take a lot of risks and are willing to live almost anywhere, including the deep South, such as in Pattani. I know of four Isaan men, retired university professors, now in their 70s and 80s (one is 85) who grew up in Isaan villages, received their primary and secondary education as novice monks, and then went to either India or Sri Lanka for their college education. To me that’s quite remarkable.

“If you want to find democracy in Thailand now, you’ve got to look at hup taem,” Bonnie Brereton says.

Your word choice “the Isan Heartland” is provocative. For a place that has long been thought of as peripheral to various kingdoms, the identification of a “heartland” seems to suggest a center of gravity within the Plateau itself. What are your thoughts on the term?

In this seminar there seems to be a recognition of the culture shared by the area that includes central Isan (and not Khorat or Loei) and extends over the border with Lao PDR, where it does not include Luang Prabang. It is a smaller sub-region of what some scholars have recognized as the middle Mekong River Basin.

What’s happening is part of a movement like that of Mekong Studies programs, that focus on the societies, terrain, ecology, etc. of this area as a region that had numerous political centers before national boundaries were established.

In the same way it seems that the people who participated in this seminar view this cultural area “on both sides of the Mekong” as a distinctive center in its own right without having to view it as the periphery of a nation state.

So I like seeing people on both sides of the river view their culture as a “center” and not a periphery, which often seems to suggest an inferior attempt to imitate the center.

Even if you talked mostly about “Isaan” murals, your vision of further research really points toward a transnational framework of hup taem, linking the “Isan Heartland” with Savannakhet and Champasak Provinces in Laos.

I didn’t say much about the murals in southern Laos because I haven’t studied them as thoroughly as those in Isaan. I’ve only seen those at two wat in Savannakhet and have not seen murals at Champasak. Those in Savannakhet definitely are related to those in the “Isan heartland.”

I was so glad to hear at this seminar that Lao scholars are interested in studying them and I would expect that people on this side of the river will do some comparative work, which should be really valuable.

And because of events like the hup taem seminar, some people are starting to see this area as a distinct cultural area. So it’s not being viewed as the periphery in the way that Bangkok views Isaan. It’s interesting that some Bangkok people still talk about “the provinces” as if they were a foreign country, equating “Thailand” with Bangkok and everything outside of it as another land.

I have a sense, though, that much of this recent revival of appreciation for Isaan culture comes from above, from people holding local offices and professors. What do you see in young people from the Northeast today that might prove this feeling wrong?

Yes, I think it definitely comes from above. I recall that Khon Kaen University was not very active in terms of local culture until Dr. Sumon Sakonchai became president. Under him the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts introduced more courses, most notably master’s and doctorate degrees in cultural studies. At least this is how I remember it. In a phone interview once, I asked him about it and he very modestly said that it was part of his responsibilities as university president to support the preservation of local arts and culture as part of national heritage. And even before that it was Dr. Vanchai Vatanasapt who as KKU vice president initiated a project around 1980 to promote and preserve local village temple murals and architecture. Interestingly, both of these leaders were from the Central Region.

In recent years, the Faculty and the KKU Cultural Affairs Office have become very active, numerous Thai books on huup taem and the Sinxay epic have been published, and for several years the Khon Kaen Municipality played a big role in promoting Sinxay. Social media, especially Facebook, have picked up on this and to some extent it’s become part of a trend to post cool pictures of hup taem – and of woven textiles from the various ethnic groups in Isaan.

Nowadays, you live in Chiang Mai, a place where cultural tourism is central. How are young people there embracing this “Lanna” renaissance?

It all began in 1995 with the celebration of Chiang Mai’s 700th anniversary after which the term “Lanna” spread everywhere, even as it had hardly been used before then. Since then, the costumes worn in processions at festivals have gotten more and more elaborate, and maybe less historically accurate.

The cultural activities here include the “traditional” Chiang Mai University “freshie” trek up Doi Suthep, which many alumni come back to participate in. It begins with a procession with students carrying elaborate offerings to a shrine at the base of Doi Suthep devoted to Khruba Siwichai, a monk who, by the way, not only organized the building of the road up to Wat Phra That but also was incarcerated in Bangkok for his efforts to retain local practices among the local Sangha. The event is a mixture of tradition and modernity. For faculties like architecture and art, students wear elaborate “traditional” dress, for others it’s jeans. The student announcers at this event speak kam mueang but those in some faculties do modern Thai cheers.

Similar things, initiated by professors but which students seem to enjoy, are starting to happen at some universities in Isaan as well, including KKU and Kalasin University.

I think such activities are important as they acknowledge the value of diverse local cultures and languages – especially in this age of globalization and what I call “McDonaldization,” when everything from temple murals to Thai cities begin to look alike.

**Peera Songkünnatham is a writer and translator based in Sisaket City, The Republic of Lao Lane Xang. Contact: [email protected]. This post was first published on The Isaan Record website on 20 October 2017.