Language

This story by Nicola Prentis for GlobalPost originally appeared on PRI.org on March 28, 2018, and is republished here as part of a partnership between PRI and Global Voices.

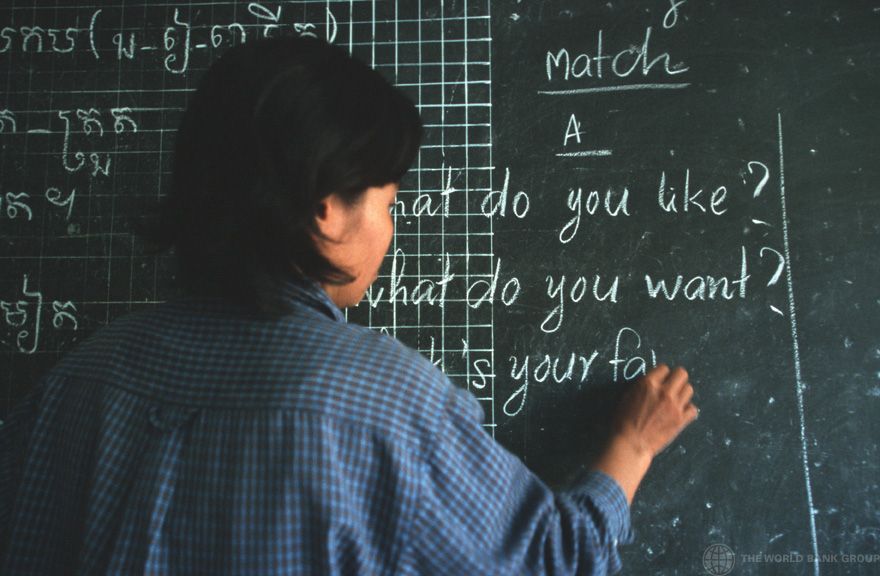

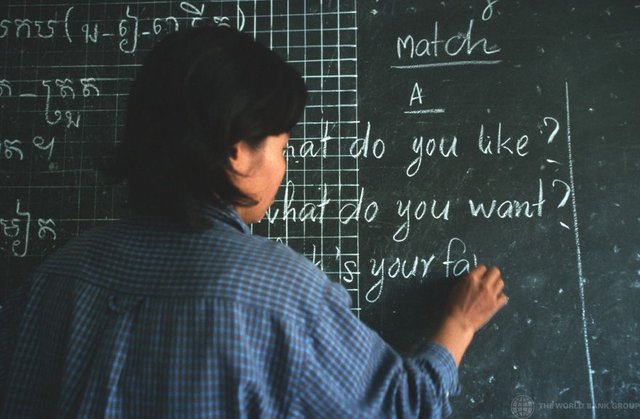

The teacher holds up a pen in the first lesson and says, “It’s my pen.” The students, English language learners who could be any age from preschool to pensioner and from any country in the world, echo, “It’s my pen.” The teacher then takes a pen from one of the students and says, “It’s her pen.” The class repeats.

Later, for review, the teacher holds up a student’s pen and invites someone to supply the right response. A student offers, “It’s his pen,” and the teacher, with raised eyebrows but an encouraging smile says, “His pen?” stressing the word to signal the error and, perhaps, gesturing to the pen's owner. The student quickly corrects the mistake: “It’s her pen.”

Globally, close to 1 billion people are learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL), and all of them encounter binary gender pronouns from the earliest lessons. It’s a grammar point covered at the beginner level. Making observations about binary gender appears in exams for young children with questions such as, “Is your best friend a boy or a girl?” and “Is your teacher a man or a woman?” But as gender awareness grows and new words and grammar around gender identity enter the language, EFL teachers are potentially at the forefront of influencing the way a billion people around the world think about gender.

In the pen exercise, there are two main ways the pronoun activity could be changed: A student describing possession could answer with, “It’s their pen.” Or, the teacher could talk about some of the new gender-neutral pronouns, so students have other options besides his or her at their disposal, should they need it — like nir, vis, eir, hir, zir and xyr.

EFL materials, on the whole, have been including singular they for years. “Everyone was talking about gender balance in materials,” says English Language Teaching consultant Frances Amrani recalling her work with Cambridge University Press in 2000. “We were encouraged to think about it on all projects. On my first project, [a course book called “Vantage”] for the Council of Europe […] we agreed that ‘their’ was commonly used as a neutral singular pronoun and that it dated back to [the 14th or 15th century].” An example sentence about singular their made it into the grammar explanations at the back of the pre-intermediate-level book.

When it comes to teaching singular they to refer to people who identify as nonbinary, it’s unlikely that course books will reflect this usage anytime soon. Although they are based on “corpus data” — huge banks of language as it is being used — EFL course books will always have a lag between when something recurs enough to have become standard in written or spoken language and when it appears in a teaching syllabus. Authors and editors also have input into what is included. “If words catch on and become widely used really quickly and are of obvious use, like ‘selfie,’ then they'll probably make it in quite quickly. Others that are a bit more niche will inevitably take longer,” says lexicographer Julie Moore.

Bearing in mind the time it takes to publish a new course book, it would mean at least another few years before “This is Sarah’s pen, give it to them” is printed in learning materials.

That might sound slow, but look at the word Ms., which took about 70 years before it was in widespread use in 1972 and was probably only established in course books in the mid-'80s.

Browsing through his collection of old books, the EFL methodology writer, Scott Thornbury, says he found no instances of Ms. in a 1976 course book, “Strategies,” (Longman Publishing Co.), but quite a few examples of Mrs. and one Miss. But, by 1979, while the textbook, “Encounters,” (Heinemann), presents the same choices for filling out an official form, including Mr., the Teachers’ Book notes:

Point out Miss/Mrs distinction. If students ask, explain Ms as modern term for both Miss and Mrs.

The Cambridge English Course Book 2 Teacher's Book (1985) didn’t wait for students to ask:

Finish by making sure that students know first name, Christian name, surname, Mr, Mrs, Miss, Ms.

Finally, by 1986, Ms made it into a students’ book with Headway Intermediate offering Ms, along with Mr, Mrs, and Miss, as an option in writing formal letters.

Could we expect a progression like this to happen faster nowadays, with the internet zapping new words around the world and into corpus databases?

Some independent, digital publishers are moving faster and with a focus on individual student needs. Sue Lyon-Jones, an EFL author and publisher of web-based courses, cites the growing trend for singular they as one of the reasons she’s chosen to incorporate nonbinary they in an online grammar lesson. But also she feels “equipping English language learners with vocabulary to talk about themselves and their identity is an important part of our job.”

Similarly, teachers in their own classrooms have a certain amount of freedom to adapt the published materials they use in class and teach language they think is important, without waiting for justification from corpus. Nonbinary they is already popping up in EFL classrooms across the world.

Leigh Moss, who’s taught in Vietnam and Italy, is using it in classes. “I teach ‘they’ as gender neutral since xe/ze isn't in common use and I have non-binary friends who prefer ‘they’ and this is how I'd use it,” says Moss.

Jessie Fuller, an EFL teacher in Brazil, agrees. “I normally use ‘they’ for gender neutral, then only get into ‘ze’ if a student seems interested.”

Teachers can always find a way to present language so it doesn’t confuse. They regularly teach incredibly complex or nonintuitive things. Take the phrase, “How do you do?” It’s typically taught at the early levels despite being a question that isn’t really a question, and it having nothing to do with the manner in which you do anything at all. It has to be taught with an explanation, at least briefly, of the social and cultural nuances that accompany it: It’s only used the first time you meet someone, only in very formal conversations and, these days, probably only with older generations or the very upper classes.

Singular they, or the concept of nonbinary pronouns, doesn’t look any more linguistically complicated than “How do you do?” and no more conceptually or culturally challenging than removing the marital status of women when you address them. Whether it will take 70 years to make nonbinary pronouns mainstream like Ms., time will tell. But teachers who teach them will spread them far beyond the 400 million or so people who speak English as a first language.