Noocratic Papers No. #3 - The Akītu Mystery

Noocratic Papers No. 3 - The Akītu Mystery: Babylon’s Sacred Drama and the King's Humbling

N.E.Y 64 May 2024

By Negus Shemsizedek

To: The Global Village

Begin all things first by using the all!

Listen to reason! The Akītū Festival stands as one of the most significant and multifaceted calendrical observances of ancient Mesopotamia, embodying profound spiritual and sociopolitical dimensions. This grand festival, observed across several Mesopotamian cities from the third millennium BCE onwards, offers a lens through which we can comprehend the interplay of divine authority, royal power, and priestly influence within Babylonian society.

From a noological perspective, the Akītū Festival serves as a prime example of how collective cognition and cultural paradigms are structured and maintained. As H.I.M. Dr. Lawiy Zodok, I perceive this festival not merely as a historical event but as an embodiment of the societal mind. The rituals reflect a profound understanding of the interplay between cosmic order and human governance, a dynamic that is central to the science of noology—the study of structured consciousness.

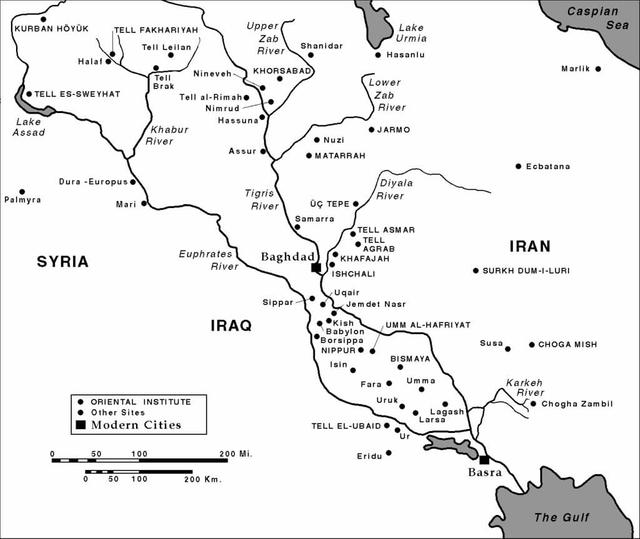

The festival’s prominence is particularly evident in its iterations during the first millennium BCE, where records indicate it occurred biannually. The spring Akītū took place in Nisannu (March-April), aligned with the spring equinox and the commencement of the Babylonian calendar. Conversely, the autumn Akītū was celebrated in Tašrītu (September-October), corresponding to the autumn equinox. Detailed accounts of these ceremonies are preserved in cuneiform texts primarily associated with Babylon and Uruk, though fragments hint at similar practices in Assyria. However, our understanding remains incomplete, shaped by the fragmentary nature of these ancient records.

Central to the spring Akītū was the recitation of the Babylonian Creation Epic, Enūma Eliš, before the cult statue of Marduk on the festival’s fourth day. This epic celebrated the supremacy of Babylon and its patron deity, Marduk, emphasizing themes of creation, order, and divine kingship. On the eighth day, an assembly of gods convened within Marduk’s temple, followed by a grand procession through the Ištar Gate to the Akītū-house outside the city walls. This ritual reenacted Marduk’s mythological victory over Tiāmat, symbolizing the restoration of cosmic order. On the eleventh day, the gods returned triumphantly to Babylon, marking the culmination of public observances.

As a noologist, I find the enactment of Marduk’s victory over Tiāmat to be a ritualized reinforcement of societal cohesion. The myth symbolizes the triumph of order over chaos, reflecting humanity’s innate desire to structure the unstructured and align with higher realms of consciousness. The festival becomes a communal meditation on the collective mind’s alignment with divine will, ensuring that societal norms and structures remain intact.

A pivotal aspect of the Akītū was the ritual reaffirmation of the king’s mandate. On the fifth day, the king entered Marduk’s temple for a private ceremony of “ritual humiliation,” a profound act of submission before the divine. Stripped of his royal insignia—scepter, loop, mace, and crown—the king was struck on the cheek by the high priest, led by the ears, and made to kneel before Marduk’s cult statue. In this vulnerable state, the king proclaimed his innocence, affirming his fidelity to Marduk, Babylon, and its sacred institutions:

“[I did not s]in, Lord of the Lands. I was not neglectful of your divinity. [I did not des]troy Babylon, I have not commanded its dispersal, I did not make Esagil tremble, I did not treat its rites with contempt, I did not strike the cheek of the kidinnu-citizens, I did not humiliate them...”

From a noological viewpoint, this ritual represents a deliberate act of collective cognition, where the king, as a focal point of societal identity, undergoes a symbolic transformation. By stripping and then restoring the royal insignia, the ceremony externalizes the fragility and conditional nature of leadership. It serves as a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of individual roles within the larger societal mind.

Following this confession, the high priest assured the king of Marduk’s favor, restored his insignia, and struck his cheek a second time. The ritual’s success hinged on the king’s tears—a performative act of penitence—signifying Marduk’s approval or disfavor. This ritual underscores the performative nature of lamentation in Mesopotamian culture, paralleling practices such as the employment of professional mourners.

The Akītū’s themes of status reversal extended to the autumn festival, wherein the king spent a night in a reed structure outside the city, deprived of his royal symbols and engaged in penitential prayers. The restoration of his insignia the following morning symbolized the renewal of his divine mandate. Such rituals reflect the conditional nature of royal authority, necessitating periodic validation from the divine and priestly spheres.

From my perspective as H.I.M. Dr. Lawiy Zodok, these practices resonate deeply with noological principles. They illustrate how rituals operate as systems of structured cognition, shaping collective beliefs and maintaining societal balance. The interplay between priesthood and monarchy is not merely a political arrangement but a noological framework where each role reinforces the other, ensuring the continuity of the cultural mind.

Scholarly interpretations of these practices suggest a nuanced interplay between king and priesthood, particularly during periods of foreign domination in Babylonia. The principal accounts of the Akītū ritual stem from the late first millennium BCE, a time when Babylonia was under Achaemenid, Seleucid, and Parthian rule. While some foreign rulers supported and even participated in these ceremonies, others view the ritual texts as expressions of priestly assertion within a context of diminished royal autonomy. Thus, the “ritual humiliation” of the king may signify not only divine subjugation but also a strategic reinforcement of priestly authority.

From a noological lens, this period demonstrates how structured consciousness adapts and evolves under external pressures. The Akītū becomes a site of cultural resilience, where rituals encode the values and aspirations of the collective mind, even amidst foreign rule. It is a testament to the enduring power of shared belief systems to navigate and negotiate change.

Ultimately, the Akītū Festival encapsulates the intricate relationship between divine will, royal power, and societal order. It reminds us that absolute authority is never exercised in isolation but relies on the collaboration and support of interconnected elites. These rituals, rich in symbolism and meaning, continue to inspire reflections on the dynamics of power, faith, and cultural identity within ancient civilizations.

As a noologist, I see the Akītū not just as a historical artifact but as a living lesson in the art of aligning individual and collective consciousness with higher principles. It challenges us to reflect on our own societal structures and the rituals we employ to sustain our shared reality.

H.I.M Dr. Lawiy Zodok

General Solutionist