The Rollercoaster Dramatization Behind 'Titanic': A Wild Spending plan, Two Warring Studios and a Close Fistfight

This year, James Cameron's Oscar-winning Titanic will mark the 20th anniversary of its release. In this second exclusive excerpt from his new biography Leading Lady: Sherry Lansing and the Making of a Hollywood Groundbreaker (Crown Archetype, out April 25), THR's executive features editor picks up Lansing's story as the Paramount Pictures chairman faces the biggest decision of her career: whether to go ahead with Titanic.

By 1996, Sherry Lansing was firmly in place atop Paramount Pictures, comfortable at last in her role as an executive after years as a producer, during which she had worked the system rather than working for it. She was hungry for good material, anxious to find the kind of dramas fueled by the intense emotions that had driven her personal life. Then she heard about a new epic whose rights might, just might, be available.

The industry was abuzz with rumors about Titanic, the first film from director James Cameron since 1994's True Lies. The movie was shrouded in mystery, its script hidden from even the most probing of Paramount's executives. But production chief John Goldwyn's wife, actress Colleen Camp, had recently auditioned for a role and soon an executive at 20th Century Fox slipped the screenplay into Goldwyn's hands.

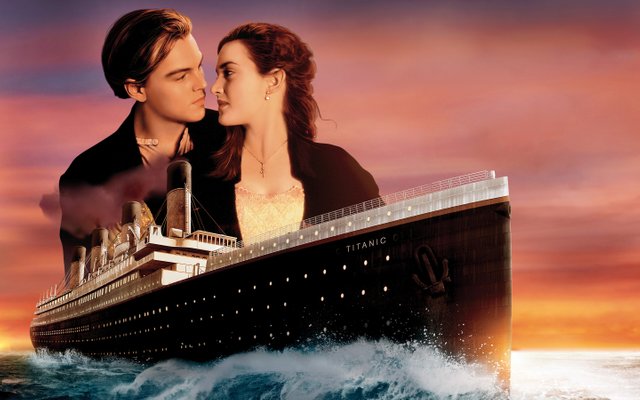

As soon as he got it, Goldwyn passed it to Lansing, who devoured it in one gigantic bite. Immediately, she knew she'd found gold. She was thrilled by the way Cameron had used a real-life tragedy to propel his fictional story, a Romeo and Juliet tale set against an epic backdrop, as modern in its themes as it was historic in its setting. The movie may largely have been set in 1912, but it was utterly contemporary in its feel.