Franz Kafka and the universe of hope

In 1963, eight decades after the birth of Franz Kafka, an international conference on his work was held in the baroque Czech castle of Liblice. Rediscovered for the world shortly after the end of World War II, Kafka had become a classic, along with James Joyce and Marcel Proust, who proclaimed him one of the "three witches" of modern literature: thousands of pages were readily expressed - enthusiastic or hostile - many more than all his small volume, unfinished works. The name Kafka hovered in the air ... For our young years, Kafka remained a deceiving secret, a forbidden fruit of knowledge. Few had read his works, but we all talked about him, we used names and facts taken from the explanatory literature on Kafka, we were discussing foreign opinions, but we did not know Kafka himself. Ah, these endless midnight talks about Kafka! The crime scene was no different. Decades after his death, Kafka continued to resent hostility, suspicion, fear; disgust; he still denounced him as an evil spirit of decadence and decay dangerous to mental health and culture. Today, exactly one hundred years after Kafka's birth, entering his literary world seems inevitable. The hundreds of monographs and studios on the "fountain" illuminate one side or another of his work, but generally speaking more about the researcher than about the writer himself. Kafka is slipping away from the intuitive interpretations - everybody finds him as much as in penetrating the labyrinth of strange images and suggestions he can find in himself. The mystery of Kafka - it's like the secret of creativity, not to tell the secret of life itself. Because the life of this writer is so organically merged with his works that every one of his lines is a pulsating remnant of his physical and spiritual being. According to Martin Walser, Kafka's "Description of a Form" study (1952) has so thoroughly mastered his life experience that exploration of his biographical background becomes superfluous.

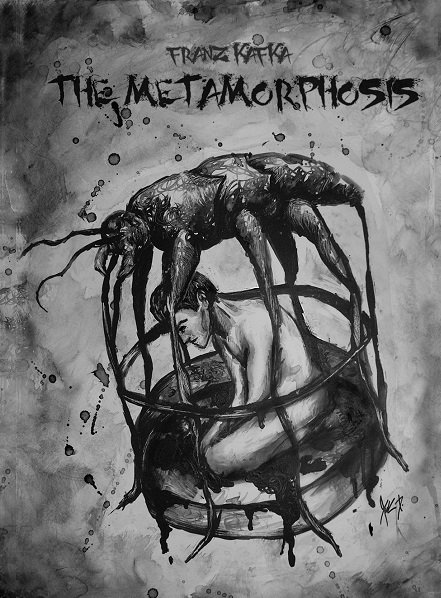

But for the same reason, perhaps an introduction to Kafka's biography will suggest something about his work. Several are the visible determinants of his artistic cosmos. First of all, it is the family environment in which the writer grew up and the relationship within it. Born in 1883, Kafka is the only son and first of four children of a middle-trader of Jewish origin. Father Hermann Kafka has moved to Prague after a long and slow occupation of the provincial towns. He is a despotic person, a man of great stature, full of self-defense against the literary endeavors of his successor. In this difficult conflict with the fatal and earthly father Kafka turns out to be hated and rejected - in the family he will forever remain a foreigner. In the famous "Letter to Father" Kafka reveals the secret atmosphere of indulgence and loneliness in the home. He and his three sisters experience the creator with fear, mixed with respect and admiration - traditional feelings in the old Jewish families. This letter already reveals the hidden struggle between power and impotence so characteristic of Kafka's creativity. The son turns to the powerful father, saying, "You really often see us together ... we whisper, we laugh, you know from time to time that we mention your name, you get the impression that we are bold conspirators ... Strange conspirators! you are, for a long time, the main subject of our conversations as well as of our thoughts, but in fact we are gathering not to make something against you, but to discuss together the terrible process that is going on between us and you - with full tension, wit, seriousness, love, perseverance, anger, dislike, loyal with all the powers of mind and heart, we look at it from all sides, from any point of view, from a distance and from a distance - the process in which you constantly insist on being a judge, and in fact (here I leave open the possibility of any misconceptions ) at least to a large extent, you are also a weak and blind country like us. " To the mother - a gentle and merciless woman with an ascetic spirit completely conquered by the gloomy charms of her father - Kafka has deep and unrelated attachment bordering on self-esteem. The only glimpse of the family is his attitude to the youngest sister, Otto, who embraces him with critical compassion. The inability to adapt to the conditions of the home, to the "father's world", Kafka has recreated in his narration "The Sentence" and especially impressive in his novella "Transfiguration".

The importance of shaping Kafka's basic art problem also has its clash with the life of the "little man," who is exposed to the impenetrable mechanisms of bureaucracy and arbitrariness of public governance. At the father's insistence, the son graduated from the law faculty of the German University in Prague and served as a trainee in a court where he dealt with criminal and then civil matters. There, he penetrates the hidden motives of justice, witnesses a number of absurd "processes" and "judgments." According to Elias Canetti, Kafka has known and depicted the power in all its varieties. And with the inhuman exploitation, the writer collides at the Accident Insurance Institute, where as a clerk he spends a decade. He knows the bits of the hired workers, their alienation from the products of their labor, from the outside world, and ultimately from themselves. In her diary, Kafka writes: "Yesterday at the factory, the girls - in unbearable dirty and distraught dresses, hairy, disheartened like waking up in the morning, with a stone expression on the faces caused by the continuous noise of transmissions and various automatic but permanent stopping machines - they do not look like people, they do not greet them, they do not apologize ... "And in a conversation with his close friend, writer Max Brod, Kafka says:" How modest these people are, they come to pray. they storm the institution and do everything in the dust and dust, they come and pray. " His impressions of the spiritual and physical mutilation of the little man Kafka has invested in his narrative "In the Penal Colony". The hundreds of monographs and studios on the "fountain" illuminate one side or another of his work, but generally speaking more about the researcher than about the writer himself. Kafka is slipping away from the intuitive interpretations - everybody finds him as much as in penetrating the labyrinth of strange images and suggestions he can find in himself. The mystery of Kafka - it's like the secret of creativity, not to tell the secret of life itself. Because the life of this writer is so organically merged with his works that every one of his lines is a pulsating remnant of his physical and spiritual being. According to Martin Walser, Kafka's "Description of a Form" study (1952) has so thoroughly mastered his life experience that exploration of his biographical background becomes superfluous.

But for the same reason, perhaps an introduction to Kafka's biography will suggest something about his work. Several are the visible determinants of his artistic cosmos. First of all, it is the family environment in which the writer grew up and the relationship within it. Born in 1883, Kafka is the only son and first of four children of a middle-trader of Jewish origin. Father Hermann Kafka has moved to Prague after a long and slow occupation of the provincial towns. He is a despotic person, a man of great stature, full of self-defense against the literary endeavors of his successor. In this difficult conflict with the fatal and earthly father Kafka turns out to be hated and rejected - in the family he will forever remain a foreigner. In the famous "Letter to Father" Kafka reveals the secret atmosphere of indulgence and loneliness in the home. He and his three sisters experience the creator with fear, mixed with respect and admiration - traditional feelings in the old Jewish families. This letter already reveals the hidden struggle between power and impotence so characteristic of Kafka's creativity. The son turns to the powerful father, saying, "You really often see us together ... we whisper, we laugh, you know from time to time that we mention your name, you get the impression that we are bold conspirators ... Strange conspirators! you are, for a long time, the main subject of our conversations as well as of our thoughts, but in fact we are gathering not to make something against you, but to discuss together the terrible process that is going on between us and you - with full tension, wit, seriousness, love, perseverance, anger, dislike, loyal with all the powers of mind and heart, we look at it from all sides, from any point of view, from a distance and from a distance - the process in which you constantly insist on being a judge, and in fact (here I leave open the possibility of any misconceptions ) at least to a large extent, you are also a weak and blind country like us. " To the mother - a gentle and merciless woman with an ascetic spirit completely conquered by the gloomy charms of her father - Kafka has deep and unrelated attachment bordering on self-esteem. The only glimpse of the family is his attitude to the youngest sister, Otto, who embraces him with critical compassion. The inability to adapt to the conditions of the home, to the "father's world", Kafka has recreated in his narration "The Sentence" and especially impressive in his novella "Transfiguration".

Thus, the disease paradoxically gives Kafka a creative power and insight into the spirit, revealing to him the dark, non-heated side of human life. In addition, suffering gives Kafka some holiness, mental purity and lightening. Hermann Hesse calls him a writer with an extraordinary intensity of visions who fervently envies the reality and formulates the most intimate questions of being.