Gallel's Heir Chapter 6: The Lesson of the Naya

He shall carry the world and mend the deepest wounds.

He shall illuminate the darkest corners

and brighten sadness to joy.

His touch shall heal the world.

He shall raise the dead to life.

There is no life without death.

—Sirah Anath Sorrel Albandor of Dunaya

The clock struck late afternoon, and Canúden arrived in one of Gallel's middle galleries. It was a long, gaudy room full of portraits, a purple carpet, and musical instruments: a lute, a theorbo, a vice-guitar, and others with strings or holes. Four windows, as tall as the high ceiling, brightened the room. An easel with a clamp and thin sheet of polished wood, a few stools, and two tables, cluttered one corner. Cushioned couches and bookshelves lined the periphery. The calming, citrusy smell of oil paint infused the room.

As much as Canúden disliked the gilded frames, the paintings on the walls opposite the windows fascinated him. Scores of Kel Tutang's forbears seemed to look down on him from floor to ceiling, even when their eyes stared in different directions. He marveled at the styles of dress through the generations. Did women really wear such stiff, high-necked dresses? The royals' expressions and postures hinted at their characters, self assured and content, or prideful and angry. How old were the most ancient portraits? A thousand years maybe? Would one of his paintings end up there, to stare down on another art student a thousand years hence?

Pol del Allen briskly entered the gallery with a packet of papers under his arm. An older gentleman with short, steel-colored hair, he carried himself well. The roughened lines on his face depicted good health. Some women might still find this man's toned arms and body attractive. He wore a loose linen shirt and a del's vest, red but tatty; he wouldn't likely wear his nicer clothes for an art lesson. He smiled and held out his free hand as he approached Canúden. "Good afternoon, den Ubal," he said.

Canúden smiled back and warmly took his master's hand. "Good to meet you, del Allen," he said. "You are the art master?"

"Of course," said del Allen. "You will do as I say, and become great. Or not become great, depending on your talent." Del Allen spread his right arm wide. He spoke, not with arrogance, but with the authority of someone who knew his art. "Everyone can learn to scrawl lines, but not everyone can paint murals in Gallel, or paint a face someone would want to buy. Fewer can paint something that would move a person's heart. What do you hope to accomplish here?"

Canúden laughed. "Accomplish? I want to learn to paint."

Del Allen snorted familiarly, setting his papers on the table next to the easel. "I know that. Everyone can learn to paint — not well, perhaps, not with passion, but well enough. What do you want to do with it?"

"I... don't know. Paint murals in Gallel."

"Ah, you want to replace me!" Del Allen gently slapped Canúden's cheek; his fingers were soft, not calloused like Ma's, and stained with purples and greens. "It's all right, boy. My time's almost up. I'm older than I look, and I'll want someone I trust to replace me. You won't be great for years to come, if ever, and then you'll be great forever. Take a seat at the easel. You're going to draw a naya."

"One single fruit!" Canúden hadn't known what to expect, but it wasn't this.

Del Allen held up a finger. "If you're going to draw something more complicated, you need to know how light reflects." He pulled a naya from his pocket and placed it on the darkwood table several paces in front of the easel. Sunlight from the windows illuminated the green and purple patches of color, the side closer to the window brighter, and the side closer to the table dimmer. "What do you see? What colors?"

"Uh, green and purple." Color danced before Canúden's eyes, details that touched points in his mind like gentle caresses. He squinted. "Maybe yellows and reds. Pink? Orange?"

"Good eye, son. Most people would have stopped at green and purple. Do you see how the shadow wraps around the fruit? The shadow embraces the light, and the light embraces the shadow."

"There's a ring of light around it!"

"Yes, it reflects," said del Allen. "You will see that everything has a ring of light. You will become great, den Ubal, if you see the light now. Know this: blackness doesn't exist, except in the absence of light, and in the hearts of people. Everything is color and light, and shades of dark. Know this: We cannot have light without dark, otherwise all would be blinding. There is no life without death. This is the lesson of the naya. It gets its shape from patterns of light and dark; man gets his shape from patterns of light and dark in his life. Darkness used properly in a painting will add depth and life; used improperly, it will make it muddy, vague, and unpleasant to look at. But painting is a lesson of another day. Today I want you to focus on shape. Draw the fruit."

Del Allen clamped a sheet of creamy paper onto the easel board, and gave Canúden a sharpened pencil as long as a finger. Canúden's heart thumped. He held the pencil against the paper and said, "Uh, where do I begin?"

"Start with a circle," said del Allen, "and ignore for the moment everything I said about light and shadow." He took paper and a smaller board, and sat on a stool nearby, with the board on his lap.

He touched his pencil onto the paper and drew. "A naya's not a perfect circle. Squint and look at the outline. Where are its bumps? Where does it deviate from roundness?"

Canúden began his own sketch, partly following del Allen's lines, and partly squinting at the naya. His circle became far too oblong; he grunted. "Is there a gum stick?"

Del Allen paused. "You'll never be able to erase if you press that hard. Another lesson: Never draw anything you can't erase, until your hand is sure. Otherwise you'll end in a mess, which you will if you try to erase that. Just like life, drawing is about self control. Notice the depth and texture of my lines. Start again somewhere else on the paper, but this time press as lightly as possible. I don't care if I can see your first outline clearly, as long as you can see it. When it's right, then you make it as dark as it needs to be, and even then press gently. The artist, whether great or not, is truly the master of his pencil. It will do whatever you tell it to. Your life will do whatever you tell it to."

Canúden nodded, and traced lines again, this time just touching his pencil onto the paper. He felt more in control, more able to make changes should he decide to fix a line. His naya again became too oblong in a different direction; he lined over the mistake, traced and retraced the fruit's curves on the paper until he thought his outline looked like the naya's.

"It's pathetic," said Canúden. "I've spent an hour on it, and it looks pathetic."

"I'm impressed," said del Allen. "You show some raw talent. Wonderful for your first lesson. Now." He showed his work, images of the naya in five stages of completion, from a base outline to a gray and cream fruit that seemed to sit on the paper. The art master pointed to the last stage. "What do you notice about the shadows?"

He studied del Allen's lines. "They go all around the circle. It's not darkest at the bottom. Or lightest at the top."

"Very good. What else?"

"Well." He squinted at the lines. "There's no exact spot where the dark begins and the light ends."

"Good. Spheres don't have lines, they have shades. However, notice on this stage," he pointed to the second, "I have the shadows outlined. Squint and outline the most dramatic changes. Don't worry about the exact locations; drawing is not exact, neither is life."

Canúden outlined the naya's shadows, tracing areas where the shadow met the light. He felt pleasantly dizzy with the effort. "I've made it look like a soup bowl."

"Here's a gum stick." Del Allen pulled a brown, linty clump from his pocket. "I didn't give you one earlier because gum sticks only confuse new students. They always think they have to erase everything. Just lighten the strokes on that edge, and darken that spot, and it'll look almost like a rock. Maybe next time you can make it look like a naya. Once the sun's gone, our lesson will be over."

Canúden erased the strokes, and grunted because they were gone. "Smite me, now it looks like a horse shoe!"

"You've got to learn how to erase only what you want. You're in control. Learn how to use that control, and you'll be great."

Canúden squinted at the naya again, but brightness had left the sunlight that slanted into the windows, and the naya's shadows no longer matched what he had drawn.

Del Allen stood and gathered his papers under his arm. "Very good, den Ubal. Meet early afternoon next week, and we'll have longer to work." When Canúden stood, the art master grasped the clamp holding Canúden's paper.

"May I take some paper to practice on?" said Canúden. "I... don't want to stop."

Del Allen shrugged, but grinned. "Those who are great never want to stop." He handed Canúden a thick stack of paper. "Draw what you want, show me in two days, rather than next week. I am curious of what you will produce. I advise you keep it simple. Impress me. Show me why I agreed to take you as a student, and why I usually have lessons no more than once a week."

Canúden's mouth opened wide in a grin, his arms filled with energy, ready to dance. "Thank you!"

"Siran Dylin saved Rebeck." Del Allen's lips twisted into warmth. "I owe Dylin my sanity. I think I will enjoy teaching you."

Canúden shook the master's hand and strolled to the corridor which headed to the north stairwell, to show Dylin that del Allen had come through and taught the lesson.

Boreck, Tutang's burly personal guard, stopped him after Canúden went up two steps. His expression was always haughty, and Canúden disliked him nearly as much as he did Tutang. "Kel Sinclair wishes to see you," he ordered.

"Oh?" Canúden's fingers flexed on the banister, his stomach tightened. So Boreck wasn't escorting him out of the palace after the frog incident. "Why?" Tutang's guard was playing errand boy for the treasurer?

"It's not my place to question his requests. Come now."

Canúden sighed, his fingers twitching on his packet of paper. It would do no good to argue it. Likely Galia's treasurer would make the meeting brief, and Canúden could get to Dylin's and then to drawing at home soon enough. He followed Boreck to the extravagant south corridor, where the offices of the Council of Six lay. Boreck knocked on a door, then came a tremulous, "Come in!"

Inside the office sat little kel Sinclair behind a table cluttered with books and papers. Ink covered his trembling fingers. A map of the world hung on the wall behind him with pins stuck in towns. Shelves of books obscured the plain walls, even under the map. There were no windows; only a lamp and a glowing fireplace lit the small, dank room. "Ah, den Ubal," he said. He rose half way to shake Canúden's hand; the squeeze was firm and quick, but Canúden felt only three cold fingers in it. Boreck grunted and left. "I am so pleased to see you. I apologize about the mess, I never seem to get around to tidying. So much to do."

Canúden folded his arms and drummed his fingers on the packet of paper.

"Yes, den Ubal, you must wonder why you're here. Yes, why." The treasurer glanced around the room as if to find his chair, then sat. He distractedly pushed papers together in something leading to order and knocked over a half-filled ink bottle. "Oh, curses," he said. He patted his pockets and pulled out an ink-blackened handkerchief, with which he blandly mopped the spill.

"What can I do for you?" said Canúden.

Kel Sinclair glanced up from mopping the table. "Oh, yes, den Ubal. His Royalness the Kel has an offer for you which he, um, believes you will enjoy."

Canúden's chest tightened. Kel Tutang would want nothing good with a village boy. "An offer?"

"Yes, yes. An offer. Let's see." He tapped his forehead and left a dark ink smudge. "Oh, yes. He wants you to figure how to manage and keep Galia's gold."

Canúden shifted his feet. "Isn't that your job?"

"Well, it would seem so," kel Sinclair attempted a smile, "but His Royalness wants you to do it."

"I don't want it!" Canúden's voice shrieked more than he intended. "What about you?"

"What? Me?" said kel Sinclair. "Yes, well. As far as I know that has not been decided yet."

"You won't leave the Council!" Canúden was not sure of Chalock kel Sinclair's family history, but he thought his father had fallen on hard times. If kel Sinclair left the Council of Six, he may have nothing to support him. "Surely the Kel can't expect that!"

Tutanghad seemed rather too friendly in the library.

"My mother has an estate up near Tenwick, the Turbians didn't take it over, thank Anath."

"I can't take your job. I'm only eighteen. How could I be a member of the Council of Six? Doesn't there need to be some experience, or background? A minimum age?"

"I wondered that myself," said kel Sinclair, "but His Royalness was very explicit on wanting you to head the treasury."

"But why me?" said Canúden. "You're perfectly capable of doing a fine job."

The treasurer smiled, maybe thankful at Canúden's reluctance. "Well, I would hope so. I've been here for over twenty years. Gallel's books are right on budget every month. And I already have a good assistant. "

Canúden's brain jumbled and clouded and he leaned against the door behind him. "I have no experience. I know nothing about money. People don't realize that mathematics and finance are not the same thing." He didn't add that he dreaded the tedium of staring at numbers all day in such a dark office.

"You do mathematics, then? Yes, I did that in my younger years. You'd possibly do well as treasurer, after a fashion, den Ubal, when you learned how to do it."

"You can be at ease. I'm not taking your position, not ever, not even if I knew everything about it. I'm a village boy through and through, and I'd rather die than have a title forced on me. I'm here serving in Gallel only so I can get access to the library."

"Yes, I've seen you studying some evenings. Wonderful place to read." The ink on the table now smeared, kel Sinclair returned his black handkerchief to his pocket. "You don't want a title?"

"What do I care for a blasted title when I have everything I want?" Canúden stood straighter. "Please tell Kel Tutang that I decline his offer."

Kel Sinclair smiled with apparent relief. "Yes, thank you. I was afraid you might accept, and I don't know what I would tell my bondwomen. I have two, lovely, delightful women, no claim to anything but through me. And if I was removed, well, you may imagine, even with my mother's estate."

Canúden was too agitated by now to visit Dylin; he'd visit her another day. He returned home as night fell. Ma sat in her easy chair by the front room window, crocheting a blanket for a neighbor's new baby. A glowing lamp lit her work, and she looked pale and tired, her plump cheeks sunken. Her auburn hair was tied in a round knot with no strand out of place. A blanket covered her legs, which were stretched onto an ottoman. A fire crackled in the fireplace, casting dancing shadows on the coiled rug. A book lay open with a pencil under the lamp; she'd been writing in her journal, as she did most evenings. Half of the books on the shelves were the writings of her life, and sometimes her made up stories; the others were those left to them by Gizelle.

"Hello, Ma." He folded his cloak onto another chair and kissed her cheek.

"Dinner's waiting for you, dear." A bowl of soup and a loaf of bread stood on the table in the kitchen. "How was it today?"

He smiled and sat at the table to eat. "Drawing is so... satisfying, now that I'm finally learning how. Del Allen is a good man. But guess what?" He recounted his experience with the treasurer.

"Well, you'd do well, but you'd be miserable." Ma laughed. When she moved, she grimaced.

"Is your knee hurting again?" The brute who'd attacked her when she was sixteen, who'd given her Canúden as a result, had broken her knee. It had long been healed, until she'd stumbled on a root and fallen last Ansday.

"Don't worry. I'm fine, just a little tired."

He knelt at her side. "I worry about you, Ma. You've lost weight, and you look pale."

"It's just age. It's nothing, really." She laid down her crochet and rested a hand on his shoulder.

"You're not old," he said.

"Maybe so. My knee still hurts."

"I can bring Dylin here to heal you. I'm sure she'd like to meet you."

She smiled. "I never thought you'd make friends with a royal."

"She's not like other royals."

"She must be special if she shared a dream with you. Can she heal an old wound?"

"You're not old!"

"No, but the wound is."

"She can heal anything." He returned to his meal. "She'll love you."

"Don't make a special trip, but next time you see her, do invite her. We can have lunch together next week."

Canúden nodded, enthused at the thought of bringing Dylin home. "I can't believe Tutang wants me to take another man's position."

Ma shifted. "He's pompous."

"Even without the stupid title, I can't even imagine advising him. Why would he listen to me?"

She wove the yarn around her fingers and resumed crocheting. "It's the most skilled advisers who find a way to make him listen. No, Tutang is a fool. You're happier as an artist."

He told her of the day's events, the frog sandwiches, and details about his lesson.

When she laughed, the tension eased from her face.

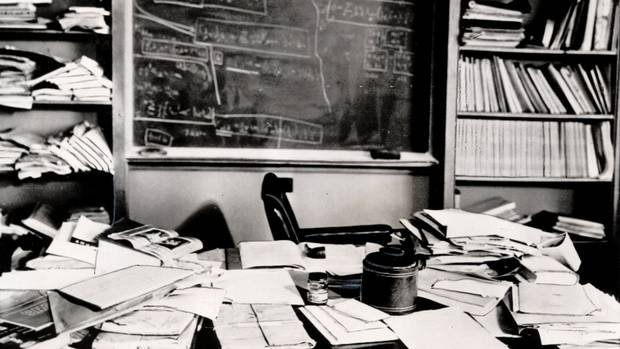

Images courtesy of

casandrarose

Einstein's desk: Messiness Shows Creativity

Don't miss any of the chapters!

Prologue: River Flowing

Chapter 1.1: Blindness

Chapter 1.2: Eyes Opened

Chapter 1.3: Hallel's Star

Chapter2.1: Hope

Chapter 2.2: Relevance of Freedom

Chapter3.1: Power

Chapter 3.2: Death's Power

Chapter 3.3: Power of Life

Chapter 4.1: Encounters

Chapter 4.2: Encounters

Chapter 5.1: A Galian Delicacy

Chapter 5.2: A Galian Delicacy

The author is clearly a painter. The use of words to paint the imagery is just stunning. Great work!

Just curious, what's the hardest article you've had to edit so far?

Do you mean here, or what I've edited anywhere?

Lengthy, technical articles are difficult. But I have always been successful to make the writer sound professional.

This post has been ranked within the top 80 most undervalued posts in the first half of Jan 09. We estimate that this post is undervalued by $4.79 as compared to a scenario in which every voter had an equal say.

See the full rankings and details in The Daily Tribune: Jan 09 - Part I. You can also read about some of our methodology, data analysis and technical details in our initial post.

If you are the author and would prefer not to receive these comments, simply reply "Stop" to this comment.