Why work with Escherichia coli (E. coli)?

It would probably be difficult to find a molecular biology laboratory that didn’t have a freezer full of E. coli. Species that are commonly used in biology labs are called model organisms. You will find that there are people that can cite numerous reasons why one particular organism is a “bad” model organism but, in practice, there is no perfect model organism. This essay will describe some of the reasons why scientists use E. coli.

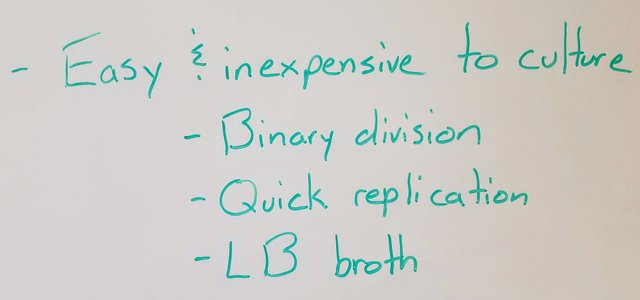

Ease and cost are two factors that should be a considered when working in a lab. E. coli excels at both of these. The first two talking points (figure 1) are the facts that, like all bacteria, they reproduce by binary fission and, unlike all bacteria, they can do so very rapidly. Under optimal conditions, E. coli can replicate about once every 20 minutes. In contrast, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a much slower optimal growth rate (1).

The final talking point in this section is that the medium (typically Luria-Bertani broth or “LB” broth) is both easy to make and inexpensive. The ingredients are 10 grams tryptone, 10 grams sodium chloride (table salt), and 5 grams yeast extract per liter of water (2). Add some E. coli to LB broth, heat it up to 37 degrees Celsius (aka body temperature or 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit) and shake it at about 200-220 rpm to aerate the sample and the bacteria will multiply for you.

Figure 1: Benefits of working with E. coli (part 1)

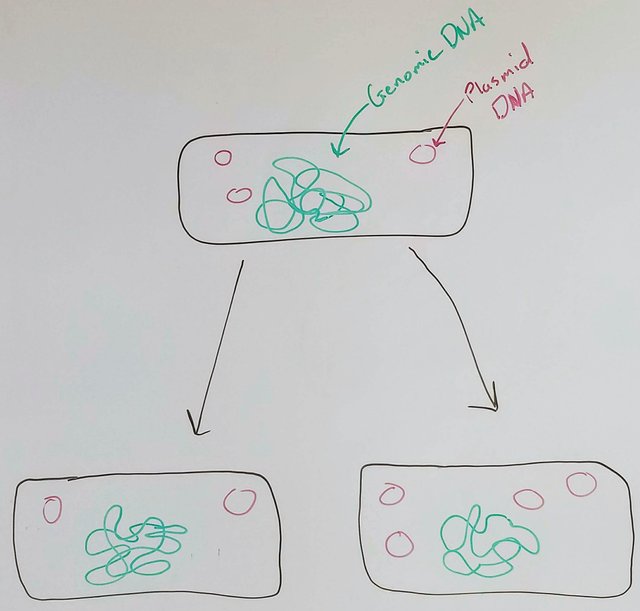

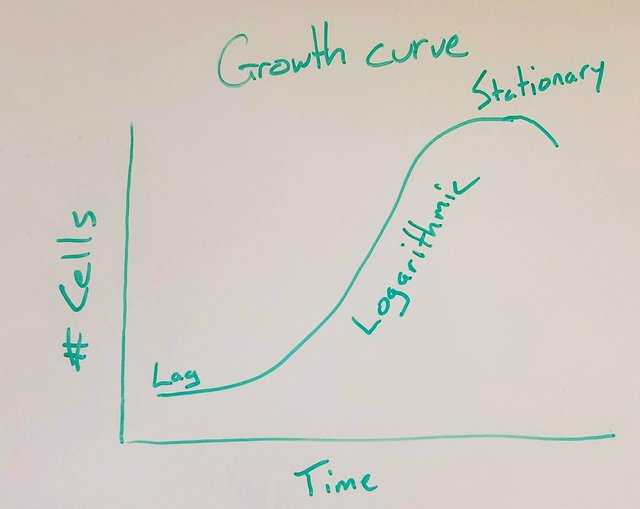

Bacteria replicate by binary fission (figure 2). This means that one “parent” cell will divide into identical “daughter” cells. As the bacteria continue to replicate, their population size will repeatedly double. A generic growth curve is shown in in figure 3. At first the doubling rate is slow and this represents the “lag” period of growth. Next, the replication is optimal and this growth phase is referred to logarithmic (or “log”) growth. As nutrients become limiting, the growth rate slows to a standstill (stationary phase). After this, the bacteria will begin dying faster than replicating and the population will crash.

Figure 2: Replication by binary fission (one becomes two)

Figure 3: Typical growth curve

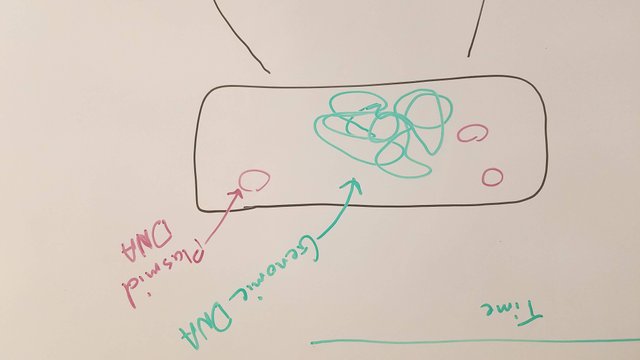

When certain species of bacteria are placed in a stressful environment, such as higher than normal temperatures, they can increase their activity of taking up DNA from the environment through a process called transformation. E. coli can be grown in such a manner as to increase the competence of taking up DNA in response to stress. In fact, we follow a protocol for making competent bacteria to create an inexpensive source of these in my lab. The extracellular DNA that is picked up from the environment can be in the form of plasmid DNA (figure 4).

Figure 4: Chromosomal (genomic) and extrachromasomal (plasmid) DNA in E. coli

Like genomic DNA chromosomes, plasmid DNA is circular. Each plasmid has an origin of replication (aka “ori”) that will recruit the same DNA replication machinery used in replication of genomic DNA. Depending on the sequence in the origin of replication, the plasmids will be found at varying concentrations in each bacteria.

Many cellular and molecular biology research tools are built from plasmids that were created and modified for a particular purpose. Common and useful genetic elements in a variety of plasmids will be covered in a future post.

Figure 5: Benefits of working with E. coli (part 2)

In conclusion, it’s the ability of E. coli to make copies of plasmids is what makes them such a welcomed addition to most biology laboratories. The last aspect to discuss in this post is the ability to easily and cheaply store these plasmids and plasmid makers (figure 6). Monocultures of unique strains of bacteria that copy a specific plasmid can be stored in a 50-50 glycerol/growth medium mix at very cold temperatures (typically -80C). Amazingly, these “frozen” cultures can be stored for years to decades in this state.

Alternatively, cultures of bacteria can be busted open and, through a plasmid preparation procedure, the plasmid DNA can be purified. The plasmid DNA is usually stored in water (or Tris-EDTA buffer) at -20C for months to years.

Finally, if you’d like to ship some plasmid DNA through the mail to a collaborator, just drop some plasmid solution onto heavy weight paper and let it dry. If you circle where the plasmid dried, your collaborator can cut out that area of the paper and suspend the DNA in some water. A quick bacterial transformation will produce plasmid makers at the destination site.

Figure 6: Benefits of working with E. coli (part 3)

References

1. http://mmbr.asm.org/content/72/1/126.full

2. http://cshprotocols.cshlp.org/content/2006/1/pdb.rec8141.full?text_only=true