Mysterious Sounds: The Source Of The World's Sound Riddle

One Saturday morning in 2010, Jody Smith, a resident of Carolina Beach, North Carolina, was disturbed by a rather unusual, rapidly growing sound. She was not alone, for when she ran out into the street, she crashed into the crowd of neighbors, also disturbed by this noise. A clear blue sky excluded the possibility of thunder. Then Smith returned to the house and on Facebook posted a message in which she asked all those who heard these sounds to respond. A few minutes later, she received a number of confirmatory answers, some of whom were 25 kilometers from her.

Smith heard these sounds not for the first time. She says she hears such rapidly growing sounds several times a year. Local journalist Colin Hackman decided to investigate these sounds, but was simply unable to explain them by any kind of human activity. These sounds could not have produced neither military nor, for example, explosions in a career. "I've heard these sounds a few times and they really hide a secret," Hackman said.

The inhabitants of North Carolina are not the only ones who have heard inexplicable rapidly growing sounds. Information about the strange rumbling, whistling and explosions all over the world have appeared for many centuries. In the area of Lake Seneca, New York, USA, they are called "Seneca weapons", in the Italian Apennines they are described as "brontidi", which means a similar thunder, in Japan they are "yan", and on the coast of Belgium they are called "mistpouffers" or a burp of fog.

So what is their reason? Some of these sounds have quite obvious explanations, say, a storm or a collapse of ocean waves. But in many cases, such as in North Carolina, no one knows the cause of these sounds. But this does not stop people offering their explanations. And if some of their theories turn out to be correct, they can change our ideas to such an extent that we recognize that the earth itself can make these sounds.

Mysterious sounds have a long history. For example, the village of Mudus in Oregon, Native Americans originally called Machimoodus, or "a place of bad noise." In 1938, the amateur seismologist Charles Davison documented sounds that are heard throughout the UK, accompanied by explanations ranging from engine noise or a remote gun shot to the noise of a huge cluster of partridges (Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol 28, p 147) .

The most likely explanation for many sounds is thunder. These sounds are generated by the sudden expansion of air due to the sudden increase in pressure and temperature around the lightning channel. In coastal areas, the ocean can act as another source of sounds. According to Milton Garcez, an expert in acoustics from the University of Hawaii, there are many ways in which the ocean can produce rapidly growing sounds. This is the crest of the wave, falling on the surface of the ocean, the air squeezed out of the wave, a giant cloud of bubbles present in the waves or just a wave crashing into the shoreline. Such sounds are loud enough and are well known to surfers. Such sounds can easily pass over land for a distance of several miles into the interior of the land, argues Garsese (Geophysical Research Letters, vol 30, p 2264). But what people heard in North Carolina can not be explained by these reasons. Quiet weather throughout the region excludes thunder, as well as the sounds of the stormy ocean.

This attracted the attention of David Hill, a well-known scientist from the United States Geological Society (USGS), Manlo Park, California. In an article published last year, Hill pointed out that the above reasons can not explain the causes of sounds in North Carolina (Seismological Research Letters, vol 82, p 619).

However, in the case of North Carolina, Hill does not exclude that the reasons for the sounds were secret military activities at a military base nearby, such as the sounds of a jet plane or shots of naval guns. However, he points out that people reported these sounds even before this base was built and a supersonic airplane was invented. The same goes for other messages around the world.

In principle, meteorites could explain these sounds, since they can cause a strong noise at the entrance to the atmosphere, and especially if something happens to them at the same time. By the time sound waves could be heard, the visible trace that meteorites leave entering the atmosphere would have gone out long ago.

However, meteorites can not be the cause of sounds that are heard every few months or years in regions such as North Carolina, because, according to Michael Hedlin, a geophysicist at the University of California, San Diego, "if you really heard a meteorite explosion, it would probably be a one time event. "

Then the explanation of this phenomenon can lie in the field of geology. In some parts of the world dunes can make a whisper, whistle and even rapidly increasing sounds. Large dunes with a steep leeward slope are the most likely sources of these sounds (Contemporary Physics, vol 38, p 329). How the sound is formed in these dunes is still very poorly understood, but it is known that for this it is necessary to combine free-lying, almost spherical grains of sand with very low humidity. Singing sands occur in about 30 places, including California, Egypt, China and Wales.

The most exotic theory Hill considers the case when the sounds are caused by a giant release of methane. The matter is that some deep sea layers consist of methane hydrate and they are capable of releasing methane during disturbance. This gas can ignite and explode with a rapidly growing sound - as the theory says. "The problem with this idea is that methane is unlikely to come up quite suddenly and in quantities sufficient for the explosion," Hill says.

This theory leaves him only one reason for the sounds in North Carolina and elsewhere - an undetected earthquake. "The network of seismographs in this area is very rare and there could have been a small earthquake that went unnoticed," Hill says.

Hill believes that the origin of the sounds does not require a strong earthquake. Small earthquakes without appreciable fluctuations of soil occur constantly and even far from the boundaries of tectonic plates. They are often recorded only by seismographs. But this does not mean that the earthquake happened near you. "The sounds of an earthquake can spread much more widely than most people imagine," he says.

Anyone who has experienced an earthquake knows that they are not at all quiet. However, the noise that most people remember is actually caused by the vibrations of buildings, soil, but is not directly the sound of an earthquake.

Yet earthquakes are indeed accompanied by sound waves that precede the earthquake itself. Malcolm Johnson, Hill's colleague at the USGS, turned out to be the person who was close enough to the epicenter to hear these sounds. In 2008, he was hit by an earthquake when he was at the very bottom of a gold mine in South Africa near the rift fault that was about to be studied. Johnson recalls: "I was at a depth of 3.6 kilometers in a small workout within the limits of the definition of the rift, tuning tools. Suddenly there was an earthquake of 2 points, and its epicenter was 20 meters away from me. I heard a sound that sounded like a thunderbolt, to which a complex high-frequency noise was imposed. As soon as I heard it, I realized that I will remember it forever. And this despite the fact that I was trying to avoid falling stones and realized that if this gap had passed through the workings out in which I was, I would be stuffing for a pie. "

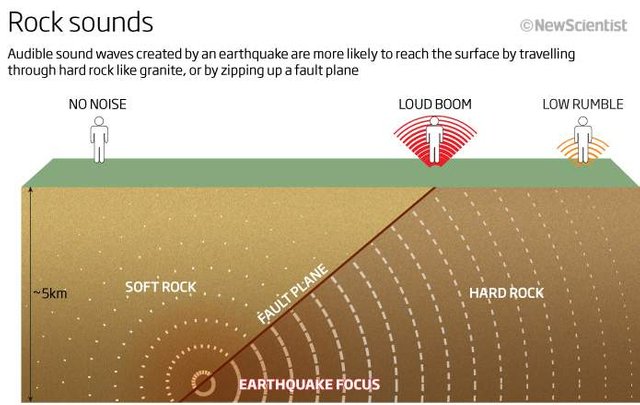

On the surface, we often fail to hear such a sound, because we are only reached by very low frequency sound waves lying outside our perception range. The waves we hear at a frequency between 20 hertz and 20 kilohertz will most likely be absorbed and scattered by rocks through which they propagate. Similarly, when you hear only bass sounds while your neighbor is playing a musical instrument.

However, under certain conditions, as Hill says, the sounds of an earthquake can be sung from the Earth. Let us give an example when a weak earthquake can excite sound waves reaching the surface. If there are solid fine-grained rocks, such as granite, in the path of sound, we are likely to be able to hear these sounds, because these rocks will dissipate the sound frequencies with less probability. Or if the waves meet on the way the interface between two media, then on it they can be transferred directly to the surface and directly into the air. "The earth around man acts like a giant bass loudspeaker," Hill says.

In addition, certain weather conditions can contribute to the propagation of sound waves over long distances. For example, a cool foggy morning, when a cold layer of air is locked under a warmer atmospheric blanket. Then, reflecting from the warm layer sounds, can "jump" over long distances.

But can weak earthquakes be undetected? Jonathan Fox, a geophysicist at the University of North Carolina, is very skeptical about such statements. "The instruments used to record earthquakes are very sensitive. If loud noises can not be caused by earthquakes, then they probably have a different nature, "he says. However, he admits that at least some of the sounds reported are due to natural causes. A lot of field observations confirm the idea that small earthquakes can be sources of strong noises. Back in 1975, Hill and his colleagues installed seismic stations in Impire Valley, California. One night, their microphone recorded three rapidly increasing noise, which completely coincided with three earthquakes, magnitudes 2 and 3 points (Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, vol 66, p 1159).

Later, Matthew Silvander of the University of Toulouse, France, recorded a rapidly growing noise associated with small earthquakes in the French Pyrenees. "When an earthquake is right under your feet, you hear a rapidly developing sound, but if it is far away - the sound will be lower in tones. Probably, for many funny noises you can put responsibility on the tectonics, rather than the poltergeist, "says Silvaner.

North Carolina with its constant noises could be the place in which it will be possible to resolve this secret once and for all. The EarthScope project is a network of seismic stations located at a distance of 70 kilometers from each other, covering the whole of the USA from west to east. In a few years, she must reach North Carolina and be sensitive enough to test Hill's earthquake theory.

Just started to collect reports on the sounds heard by earthquakes. For example, Patricia Tosi of the National Institute of Geophysics and Vulcanology in Rome, Italy, and her colleagues ask people to report on the sounds of earthquakes they have heard through online questionnaires. Using this data, they reproduced a map of the noise heard by the 6.3 magnitude earthquake that struck the city of Aquila in 2009. Many of these sounds were most likely caused by fluctuations in buildings, but some of the messages coming from the 100 km zone near the epicenter are directly related to the noise associated directly with the earthquake.

No matter what the sounds that Jodi Smith heard in North Carolina that day, it seems that our planet produces a lot more sounds than we thought. The incompetence of our world means that most of us are accustomed to attribute loud noises of human activity. But the sound you take for the rumbling of a distant truck, in fact, can directly be the voice of the Earth.

Information sources : (Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol 28, p 147) (Geophysical Research Letters, vol 30, p 2264) (Seismological Research Letters, vol 82, p 619) (Contemporary Physics, vol 38, p 329) (Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, vol 66, p 1159) (Mystery booms: The source of a worldwide sonic enigma) .