The Amateur Mycologist - The Ecology Of The Magallanes Region of Chile And The Incredible Museo de Historia Natural Rio Seco In Puntas Arenas

- (Sorry about the delay in publishing this post. Although it contains no fungi, I wanted it to be researched and edifying, and the result is a miniature encyclopedia of information about the Magallanes Region of Chile and my experience there. No disclaimers today...unless you intend to eat a Guanaco, which I do not recommend.

.jpg)

A Caracara, maybe a Chimango Caracara, one of many birds of prey, taking flight off a lone tree in the Patagonian Steppe

Although we strove to see and catalog fungi every day of our trip, we were not always well situated to do so. The third or fourth day of our journey through Chile involved a fairly long drive from Puntas Arenas to Torres del Paine, one of the most beautiful and visually grand parks I've ever been too.

The problem for us as a group of amateur and professional naturalists and mycologists, travelling in the spirit of Darwin and The Beagle, was that we could hardly travel twenty kilometers without stopping to look at the local fauna or flora. The result was that a trip along Route 9 that was supposed to take 4 hours ended up taking closer to 8, and by the time we got deep into Torres del Paine to see the sad remnants of the glacier there, the sun was ominously low in the sky.

But before we go on, let's talk about the region of Chile all this - including the last two posts of mine - is taking place in.

.svg.png)

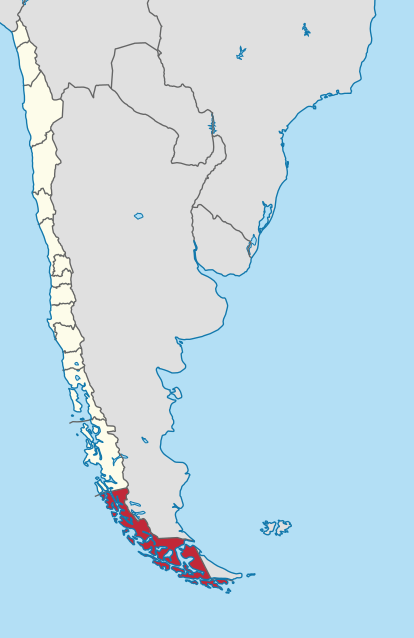

The area in red is the Magallanes region of Chile, also inclusive of the southern tip of Argentina in Tierra Del Fuego

The southermost region of Chile, it consists of numerous islands, wide expansive plains, Nothofagus forests, and towering mountains.

The Magallanes name is, of course, a reference to Magellan, who is mentioned left and right in and around Puntas Arenas. Magellan is famous the straits named after him, the largest portion of which passes by Puntas Arenas, but which then continues through the many separate islands out into the Pacific. Before the Panama Canal, the strait of Magellan was by far the fastest way around the southern tip of South America, saving substantial amounts of time compared to rounding Cape Horn.

The ecosystems down in this part of the country vary widely, and quickly at that.

Our visit there began in the Nothofagus deciduous forests, filled with short leaved deciduous trees and a great deal of moisture.

But a short drive out of Puntas Arenas along Route 9, and suddenly we are surrounded by arid steppe, flat and far as the eye can see.

This transition happens quickly, within an hours drive. You move from the moist forests surrounding the town out into an unforgiving landscape ruled over by birds of prey and carrion feeders.

As you continue to drive along route 9, over the course of a few hundred kilometers, the steppe begins to rise toward the sky, the land becoming even more arid and aggressively, inhospitably, beautiful.

Laguna Amarga, with the crags of Torres del Paine in the immediate background.

As you drive into Torres del Paine from the South, you pass a gorgeous looking blue-green body of water, perfectly still and mirroring the distant mountains. At first glance it appears almost idyllic, like a mirage after several hours in the increasingly arid landscape.

But closer examination reveals an unforgiving body of water, saline and unpalatable. All around the lagoons edge there is what appears to be a perfect white sand, which from a distance calls you to it in the hopes of a brief, refreshing dip.

However, up close the "sand" reveals its true nature.

Large crystals of mineral salts, in epic quantities, several inches deep and stretching over a meter from the edge of the water.

Amarga Lagoon, it turns out, harbors a fairly small slice of life - mostly cyanobacterias or blue-green algae - that gives the water its iridescent coloration.

Beyond that, the water is home to brine shrimp in the genus Artemia.

Brine shrimp grow and thrive in the saline waters of the lagoon in, apparently, great numbers. They are frequently eaten by a certain bird you may be familiar with.

The Chilean Flamingo is indigenous to this part of Chile and they feed on the brine shrimp in the Amarga Lagoon.

Unfortunately, we only saw two flamingos at the far end of the lagoon during our visit there, and not the large pink flocks you can sometimes witness - hence the wikicommons photo instead of one of my own. However, it is worth noting that the pink coloration of the Flamingo's plumage is purely an environmental trait, one the species derives from its diet rich in brine shrimp. It is the shrimp which lend the Flamingo's feather's their bright colors, and when you see pink Flamingo's at the zoo they are maintained that way through a very carefully planned diet - otherwise they would simply be funnily shaped white birds.

The Flamingo is one of several indigenous species which conservation efforts have worked hard to support in this region. Another is the Guanaco.

These llama-like creatures, with their extremely docile features, were nearly driven to extinction in this region over the past century.

Today, as you drive through the plains surrounding Torres del Paine you will see dozens if not hundreds of Guanacos roaming the grassy steppe in slow moving herds. However, as recently as a few decades ago this was not the case. The Guanaco was slowly but surely wiped off the landscape, having much of its natural habitat overtaken in service of another, more lucrative creature...

Sheep

So many damned sheep. There are only so many commercial uses for wide, expansive, arid steppe land, and it turns out sheep-herding is the biggest one. The wool of these massive herds of sheep provide a living to the sheep herders who dot the landscape here, but their herds also have the potential to cause massive ecological damage.

For the last century, unmitigated sheep herding did exactly that, taking over the landscape, debriding the grasslands outside and even within the national park of Torres del Paine, and leading to the near extinction of the Guanaco in this area.

However, in the last few decades there has been a large push to re-wild Torres del Paine. Sheep herding within the park has apparently been disallowed, although we did see some small cow herds inside the moister parts of the park proper. Moreover, the Guanaco population in and around the park has been given a protected status, and the result is a major increase in the population there, which was apparent wherever you looked on the way.

Eventually, you enter the park itself, and what you bear witness to is a mixture of extreme beauty and, sadly, devastation.

Torres del Paine suffered through severe forest fires several years ago, and unfortunately the low lying Nothofagus forests have not bounced back so easily.

Here you can see the skeletons of hundreds and thousands of trees stretching as far as the eye can see out to the base of the mountains. These low forests burned quickly in the dry, hot season and have not yet begun to recuperate.

The region has been receiving less rain then normal, and hotter temperatures in general, a fact highlighted most dramatically deeper inside the park.

Behold the Grey Glacier on Grey lake.

If you find yourself scanning this picture for signs of the elusive glacier you can pretty much stop. See that thin, distant white line just above water level? That's what remains. The glacier continues on out of site for some distance, but in the last decade it has receded substantially. Guiliana, our host, brought us to the park with this glacier specifically in mind, having visited it within the last five years. However, in that time the glacier has receded almost entirely out of view.

This was a major part of our trip through the country, at once enjoying the astounding natural beauty of the place, while also being punched in the face by the enormity of the ecological changes being brought on by climate change. Although this issue would rear its head mutltiple times over the course of the trip, the non-existence of the Grey glacier was by far the most dramatic.

Here, in the fine dirt revealed by the glacial lakes recession, we buried a small token for Gary Lincoff and held a brief, moving memorial in his memory.

The journey to and through Torres del Paine national park was memorable and, in part, a stark reminder of the changing state of the world's climate. There is another story to be told here when, during the two hour drige through rough hewn roads in ill-prepared minivans, we lost one of our number for several hours in the pitch blackness and nearly called the police. But this story turned out well and we found our way back to Puntas Arenas, albeit by 3AM.

The next day we would fly hundreds of kilometers north, our first hop-scotch into a very different ecosystem. But before I leave Puntas Arenas I have to mention a very special museum quite unlike any other I've ever been to.

This unassuming set of industrial looking old shacks and warehouses hide an astounding and growing achievement in the documentation of local fauna.

This is the burgeoning Museo de Historia Natural Rio Seco. Guiliana is friends with its purveyors, a small group of local biologists working on unrelated government funded projects in the region who, in their spare time, for no pay, have decided to create a unique natural history museum.

The enterprise is now several years old and the effort they have put into the project shows.

The museum grounds consist of several disused industrial warehouses.

The purveyors decided to renovate these unique spaces and fill them to the brim with the most astounding variety of expertly and artistically designed articulated skeletons of the regional wild life.

Ranging from gigantic condors, to sea turtles, right whales and even an entire wall of dozens of giant porpoise skulls, the museum presents an awesome array of macabre and instructive skeletons, almost all collected in and around Puntas Arenas, either washed up on the shore or found by locals on land.

Although they are more than capable of large, tour de force specimens, like the gigantic sperm whale they are currently working on, some of the most impressive pieces are the delicate smaller creatures arranged as though interacting within their natural habitats.

Take this gorgeous local hummingbird skeleton, displayed with the plummage intact, the super fine hollow bones arranged with immense care and suspended in order to show the bird feeding mid flight.

Or this meticulously articulated hatchling, mouth ajar, waiting forever for nutrition.

Or smaller yet, a tiny hatchling, barely out of the egg of one of the local bird species.

I was really taken by this place and these people.

They currently charge no admission fees and primarily they seem to work with the local population, giving workshops for free at the museum, where individuals come to learn about local fauna and even assist in identifying and creating the articulated skeletons.

The place is a growing work of art/record of the regions extensive wildlife. Organizations like this, created as a passion project by local scientists in order to increase local knowledge and natural appreciation, are exactly what the world needs right now. This museum has a lot of room to grow, but already it is engaging locals in the preservation and understanding of their environment, as well as edifying travellers who visit the region.

If you find yourself in Puntas Arenas, don't miss it, and be sure to leave a donation so the work can continue unabated.

Photos are my own except

[Photo 2]By TUBS [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

[Photo 7]© Hans Hillewaert, CC-SA-4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

[Photo 8]By Tragopan [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Information Sources:

- Wikipedia On Torres del Paine

- Wikipedia on the Chimango caracara

- Wikipedia on the Magallanes Region of Chile

- Wikipedia on Guanaco

- IUCN Red List On Guanacos

- Wikipedia on Torres del Paine National Park

- Helpful Blog Post On Amarga Lagoon

- "Distribution and characterization of Chilean populations of the brine shrimp Artemia (Crustacea,Branchiopoda, Anostraca)", International Journal of Salt Lake Research 8: 23-40, 1999 KluwerAcademic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands, by OSCAR ZUNIGA, RODOLFO WILSON, FRANCISCO AMAT and FRANCISCO HONTORIA

- Wikipedia on Brine Shrimp

- Wikipedia on Chilean Flamingos

- Wikipedia on Grey Glacier

- Tripadvisor Info For The Amazing Natural History Museum In Puntas Arenas

Please support @Steemstem and the #Steemstem community, dedicated to bringing and supporting high quality STEM related content on Steemit.

Let me clarify what I mean by "support." There are a number of good options.

Head over to the steemstem discord channel and the #steemstem tag and start talking with the other users involved in the community, commenting and upvoting on their submissions.

If, like me, you can hardly find time to post your own material once a week, then consider joining the steemstem autovote trail, which you can inquire about on said discord channel.

Or, if, like me, time is very difficult to give to the community, then consider making a delegation. Presently, and for the last half year, I have delegated a third of my SP to the @steemstem account.

I really liked your post! The south of Chile is beautiful! I live in the capital but I hope someday I can travel to Region de Magallanes and visit Torres del Paine :)

You really should! Or at least take a bus to some of the nearer by national parks. There is so much incredible beauty there.

Good day @dber, your post has been featured in the @offgrid-online outdoor adventure post #2, feel free to have a look and show some support to some of the other brilliant post featured ~ https://steemit.com/adventure/@offgrid-online/outdoor-adventure-2-an-offgrid-online-curation-quest

Thanks for that, I'll take a look

Go here https://steemit.com/@a-a-a to get your post resteemed to over 72,000 followers.

Being A SteemStem Member