Step away from the computer game

Some people can come up with a brilliant idea for a steemit post, then immediately sit down and dig up the required research and reading. Having spent several hours acquiring all the necessary knowledge, they then quickly take a bathroom break, drink a coffee, followed by spending the next three hours writing, editing and finally polishing. After six hours they have their finished article.

If you are one of those people, you are probably very successful and not only on steemit. It also takes me approximately six hours to finish an article, but dispersed throughout those six hours will be something like 12 hours of slowly eating lunch, feeding the cats, meeting a friend, completing some work, playing several hours of computer games to ‘give my mind a short rest’ and maybe a walk or two down to the shops. If you are anything like me you also have some problems with maintaining attention. Some good news though. Recent neuroscience research offers a little direction.

First however, let’s try and answer the question of what exactly attention is. Almost everyone has a fairly good understanding of when they are and aren’t paying attention. Stevens, C., & Bavelier, D. (2012)[1] provide a good quote to illustrate this basic understanding.

“Everyone knows what attention is…” wrote William James in 1890. “It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought… It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others…” (James, 1890, pp. 403–404).

Neurological Basis of Attention

Assuming we are highly motivated to pay attention to something, the type of attention we are interested here is known as ‘selective sustained attention span.’ This is when we make a conscious effort to pay attention to something over a relatively long period of time- five minutes or longer. Research suggests that the average person has a limit of approximately 20 minutes to remain focused on something.[3]

Explaining exactly how the brain directs its attention turns out to be very complex. Most of the recent studies on attention have used children with ADHD as their subjects. It’s obvious why these are the subjects chosen- their attention problems inflict the most suffering (primarily on their parents and teachers).

Image Source: Pexels

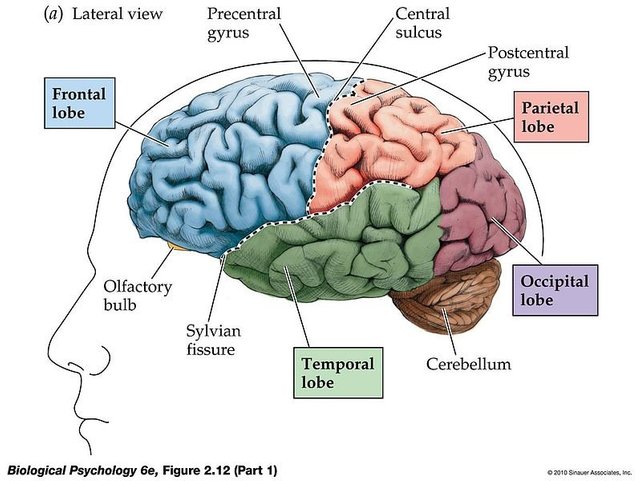

An excellent summary of what we understand about attention is provided by Stevens, C., & Bavelier, D. (2012). [1] The part of the brain responsible for controlling attention is the fronto-parietal network. In case you haven’t memorised the different parts of the brain here is a diagram displaying them:

When the fronto parietal network is activated an MRI will show part of the frontal and part of the parietal lobe lit up.

The fronto parietal network controls attention by suppressing neurons giving non-attended to information, and engaging neurons with the best discriminatory power between the attended to and distracting features. This is a dynamic process, our attention strengthens and weakens as our conscious desire to pay attention changes, and as different sensory data arrives. We could be distracted by something external such as two people talking about a party last night. We can also be distracted by internal thought processes, like our desire to check our Facebook to see if our friend has responded to us yet.

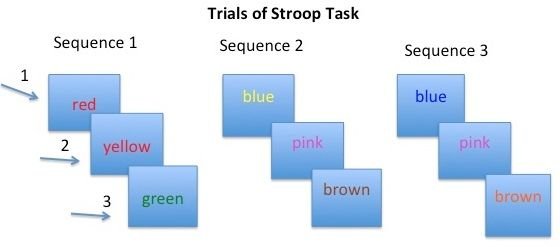

We will find it most difficult to filter information when it is very similar to the sensory data we are trying to process, and when it is providing contradictory information. The classic Stroop effect is an example of this. In Stroop (1935) [4]the subjects were given a piece of paper displaying the information in the figure below, and had to say the colour of the word they were reading. Subjects showed a much longer response time when the meaning of the word provided contradictory information, as in sequence two. Another example of this is the difficulty we find in counting when we hear someone counting a different sequence of numbers next to us.

As noted above, most research has been performed on children with ADHD. However a piece of recent research was performed on adults, and provide us with a bit of guidance on how we can maximise our comprehension and memory when paying attention to something like a lecture or a video.

Fenesi et al. (2018)[5] a research paper out just this month, looked at the question of how to maximise attention during a 50 minute video lecture. Their subjects were first-year psychology students. The students were divided into three groups, the first took no breaks, the second took three five-minute breaks to play a computer game, and the third spent the three five-minute breaks doing calisthenics exercises. The results were clear, the third group reported higher levels of attention during the lecture, and also performed better on tests measuring knowledge of the lecture content. The superior test results held both when the tests were conducted immediately after the lecture, and also on delayed tests.

This research was clearly designed around the understanding that our sustained attention will start to flag after around 15-20 minutes.

How can we apply this in our own lives?

Our university lecturers will not be too happy if we climb over the other students to walk out of the lecture every 20 minutes- then come back in five minutes later. However we can apply this when we are studying in our own time. We should take breaks every 15 or 20 minutes to go for a walk outside or do some kind of physical exercise. I remember in the past I used to have the habit of going for a walk when I felt my attention start to wander. Now my preferred method to take a break is to play a computer game! To get the best results from my study I should go back to my previous habit.

REFERENCES

Stevens, C., & Bavelier, D. (2012). The role of selective attention on academic foundations: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2(Suppl 1), S30–S48.

James W. Principles of psychology. New York: Henry Holt and Co; 1890

Sarter, M., Givens, B., & Bruno, J. P. (2001). The cognitive neuroscience of sustained attention: where top-down meets bottom-up. Brain Research Reviews, 35, 146–160

Stroop JR. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions.

J. Exp. Psychol.18:643–62.

Fenesi, B., Lucibello, K., Kim, J A., and Heisz J J. (2018). Sweat So You Don’t Forget: Exercise Breaks During a University Lecture Increase On-Task Attention and Learning. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.01.012.2.

Again, why the repost?

I agree. One should not steal articles from other steemians.

Today I just learned about the difference between cognitive reserve and brain reserve in the Understanding Dementia course that I'm doing online, in between numerous coffee breaks and other activities.

You should tell that to @flyyingkiwi, whose article was ripped over by this "author".

Good to see that steemstem is fighting plagiarism as effectively as ever. Not that this guy was hard to detect, reposting a recent article on the same website!

I think he is more of a kid. Debate-able if he learned anything but taking time to explain to every single plagiarizer our values is a losing battle :(

Believe me, I have tried!

I will! His answer was next