NASA's next Mars rover could explore former mineral springs and a fossil river delta

Sometimes, a problem really can be solved by meeting halfway. For the past 4 years, planetary scientists have wrestled over where to send NASA's next Mars rover, a $2.5 billion machine to be launched in 2020 that will collect rock samples for eventual return to Earth. Next week, nearly 200 Mars scientists will gather for a final landing site workshop in Glendale, California, where they will debate the merits of the three candidate sites that rose to the top of previous discussions. Two, Jezero and Northeast Syrtis, hold evidence of a fossilized river delta and mineral springs, both promising environments for ancient life. Scientists yearn to visit both, but they are 37 kilometers apart—much farther than any rover has traveled.

Now, the Mars 2020 science team is injecting a compromise site, called Midway, into the mix. John Grant, a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian Institution's Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., who co-leads the landing site workshops, says the team wanted to know whether a rover might be able to study the terrains found at Jezero and Northeast Syrtis by landing somewhere in the middle.

So far, the answer appears to be yes. The Mars 2020 rover borrows much from the design of the Curiosity rover that has been exploring another Mars site for 6 years. But it includes advances such as a belly-mounted camera that will help it avoid landing hazards during its harrowing descent to the surface. This capability allowed scientists to consider Midway, just 25 kilometers from Jezero and close enough to drive there. At the same time, Midway's rocks resemble those of Northeast Syrtis, says Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena and member of the Mars 2020 science team.

Midway and Northeast Syrtis both hail from a time, some 4 billion years ago, when Mars was warmer and wetter—an era never explored by a Mars rover. Surveys from orbit suggest the sites harbor rocks that formed underground in the presence of water and iron, a potential food for microbes. The rocks, exposed on the flanks of mesas, include a layer of carbonate deposits that many scientists believe were formed by underground mineral springs. Sheltered from a harsh surface environment, these springs would have been hospitable to life, Ehlmann says. "We should go where the action was."

Nearby Jezero crater has its own allure, etched on the surface: a fossilized river delta. Nearly 4 billion years ago, water spilled into the crater, creating the delta. "It's right there," says Ray Arvidson, a planetary geologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. "It's beautiful." Geologists know deltas concentrate and preserve the remnants of life; they can see that on Earth in offshore deposits of oil—itself preserved organic matter—fed by deltas like the Mississippi's. New work to be presented at the workshop by Briony Horgan, a planetary scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, will show that Jezero crater has a bathtub ring of carbonate—a strong sign that it once contained a lake. On Earth, such layers are often home to stromatolites, cauliflowerlike minerals created by ancient microbial life.

Right now, the Mars 2020 team favors landing at Jezero and driving uphill to Midway, says Matt Golombek, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, and the other workshop co-leader. For the past year, the team has scoured potential routes between the two. "We haven't identified any deal-breakers," says Ken Farley, the mission's project scientist and a Caltech geologist. The rover's advanced autonomous driving should allow it to cover more ground than Curiosity, which often stops to plan routes. Even so, the path from Jezero to Midway would take nearly 2 years, Farley says. That means the rover could explore only one site during its primary 2-year mission, when it must drill and store 20 rock cores, to be picked up by future sample return missions.

Sometimes, a problem really can be solved by meeting halfway. For the past 4 years, planetary scientists have wrestled over where to send NASA's next Mars rover, a $2.5 billion machine to be launched in 2020 that will collect rock samples for eventual return to Earth. Next week, nearly 200 Mars scientists will gather for a final landing site workshop in Glendale, California, where they will debate the merits of the three candidate sites that rose to the top of previous discussions. Two, Jezero and Northeast Syrtis, hold evidence of a fossilized river delta and mineral springs, both promising environments for ancient life. Scientists yearn to visit both, but they are 37 kilometers apart—much farther than any rover has traveled.

Now, the Mars 2020 science team is injecting a compromise site, called Midway, into the mix. John Grant, a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian Institution's Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., who co-leads the landing site workshops, says the team wanted to know whether a rover might be able to study the terrains found at Jezero and Northeast Syrtis by landing somewhere in the middle.

So far, the answer appears to be yes. The Mars 2020 rover borrows much from the design of the Curiosity rover that has been exploring another Mars site for 6 years. But it includes advances such as a belly-mounted camera that will help it avoid landing hazards during its harrowing descent to the surface. This capability allowed scientists to consider Midway, just 25 kilometers from Jezero and close enough to drive there. At the same time, Midway's rocks resemble those of Northeast Syrtis, says Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena and member of the Mars 2020 science team.

Midway and Northeast Syrtis both hail from a time, some 4 billion years ago, when Mars was warmer and wetter—an era never explored by a Mars rover. Surveys from orbit suggest the sites harbor rocks that formed underground in the presence of water and iron, a potential food for microbes. The rocks, exposed on the flanks of mesas, include a layer of carbonate deposits that many scientists believe were formed by underground mineral springs. Sheltered from a harsh surface environment, these springs would have been hospitable to life, Ehlmann says. "We should go where the action was."

Nearby Jezero crater has its own allure, etched on the surface: a fossilized river delta. Nearly 4 billion years ago, water spilled into the crater, creating the delta. "It's right there," says Ray Arvidson, a planetary geologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. "It's beautiful." Geologists know deltas concentrate and preserve the remnants of life; they can see that on Earth in offshore deposits of oil—itself preserved organic matter—fed by deltas like the Mississippi's. New work to be presented at the workshop by Briony Horgan, a planetary scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, will show that Jezero crater has a bathtub ring of carbonate—a strong sign that it once contained a lake. On Earth, such layers are often home to stromatolites, cauliflowerlike minerals created by ancient microbial life.

Right now, the Mars 2020 team favors landing at Jezero and driving uphill to Midway, says Matt Golombek, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, and the other workshop co-leader. For the past year, the team has scoured potential routes between the two. "We haven't identified any deal-breakers," says Ken Farley, the mission's project scientist and a Caltech geologist. The rover's advanced autonomous driving should allow it to cover more ground than Curiosity, which often stops to plan routes. Even so, the path from Jezero to Midway would take nearly 2 years, Farley says. That means the rover could explore only one site during its primary 2-year mission, when it must drill and store 20 rock cores, to be picked up by future sample return missions. Exploration of the second site would have to come during an extended mission, after the rover's warranty expires. "The further away you land from your gold mine, the higher the risk you might not get there," Arvidson says.

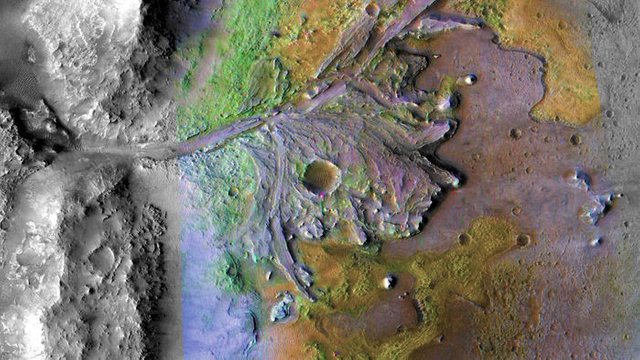

A happy medium

Jezero and Northeast Syrtis, two attractive landing sites for NASA's Mars 2020 rover, are close to each other. A new landing site, Midway, might allow the rover to study rocks from both terrains.

Left out of those plans is the last leading candidate site: Columbia Hills. "I have a sense there's a hill to climb," says the site's chief advocate, Steven Ruff, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe. "I'll go in with a lot of questions of whether they can make that drive between Midway and Jezero." Columbia Hills sits within the large Gusev crater that the Spirit rover explored from 2004 to 2010. Driving backward while dragging a bad front wheel, Spirit gouged a trench that revealed opaline silica, a mineral that on Earth is a sure sign of life-supporting hot springs. Ruff has even proposed that the martian silica deposits are stromatolites.

The engineers building Mars 2020 will be glad to settle on a destination, says Matt Wallace, the rover's deputy project

manager at JPL. The lab's clean room is starting to fill up. The "sky crane" that will lower the rover to the surface is done. The spacecraft that will shepherd the rover to Mars is nearly complete—it just needs a heat shield, which is being rebuilt after testing revealed a crack. Several weeks ago, the chassis of the rover arrived and is now being filled with computers, batteries, and other electronics. Assembly of its complex drilling and sample storage system is underway, with other scientific instruments due by the end of February. "This is the mad scramble," Farley adds. "It is full bore get it done, get it done now."

At the workshop's end, scientists will vote on the candidates, followed by a closed-door meeting of the rover team to make a final choice. Engineers have deemed the sites safe for landing, Golombek adds, so it will come down to the science. The team's recommendation won't be the final word—the choice is ultimately up to NASA science chief Thomas Zurbuchen. But expect a decision within the next few months, if not sooner.

really very interesting knowledge....

i upvote and comment your post....

i hope you will do same with me..

and pls follow me.