Let's Splice! (My Research, Vol. 3)

”So, will you splice them together?”

I don’t know why, I don’t know how, but for some reason, people associate the word “splicing” with “combining two species” or “editing a genome”. And while yes, splicing has something to do with genetics, it’s not what everyone seems to think.

mRNA, Introns and Exons

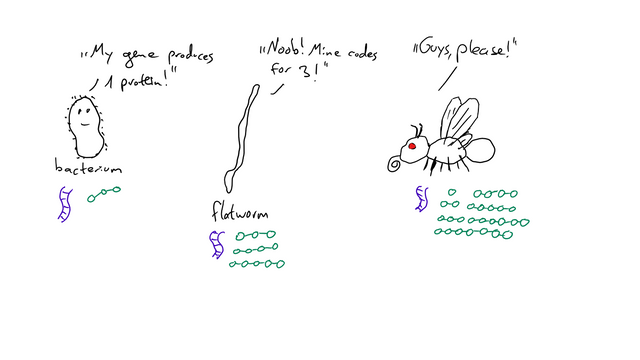

Did you know a potato has more genes than we do? That a flatworm has more genes than a fruit fly? How does that make sense? Shouldn’t a more evolved organism have more genes?

Technically, you’d be correct - if one gene would only code for one protein. But in eukaryotes (cells with a nucleus), they don’t (they do in bacteria!).

How?

For that, I need to give you a short lesson in genetics (if you know how gene expression works, you can obviously skip this part, especially because I’ll keep it very basic).

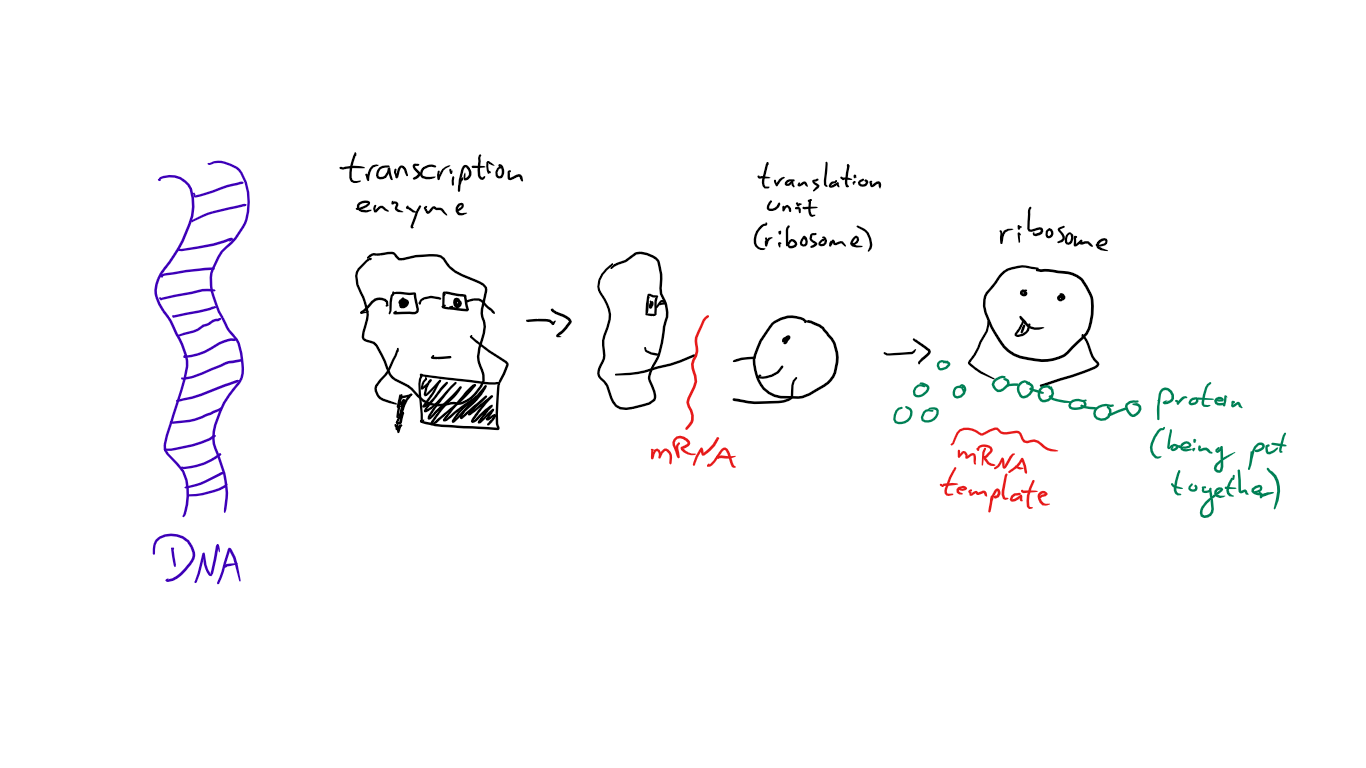

Generally, you have the DNA, which is the template for the production of proteins. But DNA is large and can’t be easily “read”, so certain enzymes are responsible for transcribing (copying) the bit that’s actually needed - which is the mRNA (messenger RNA, RNA is similar to DNA just with a slightly different structure). This mRNA is then translated into proteins. @suesa

The mRNA is the part where it gets interesting, as it can be modified before it leaves the nucleus (note: for that you need a cell with a nucleus. The things I explain after this all refer to cells with a nucleus).

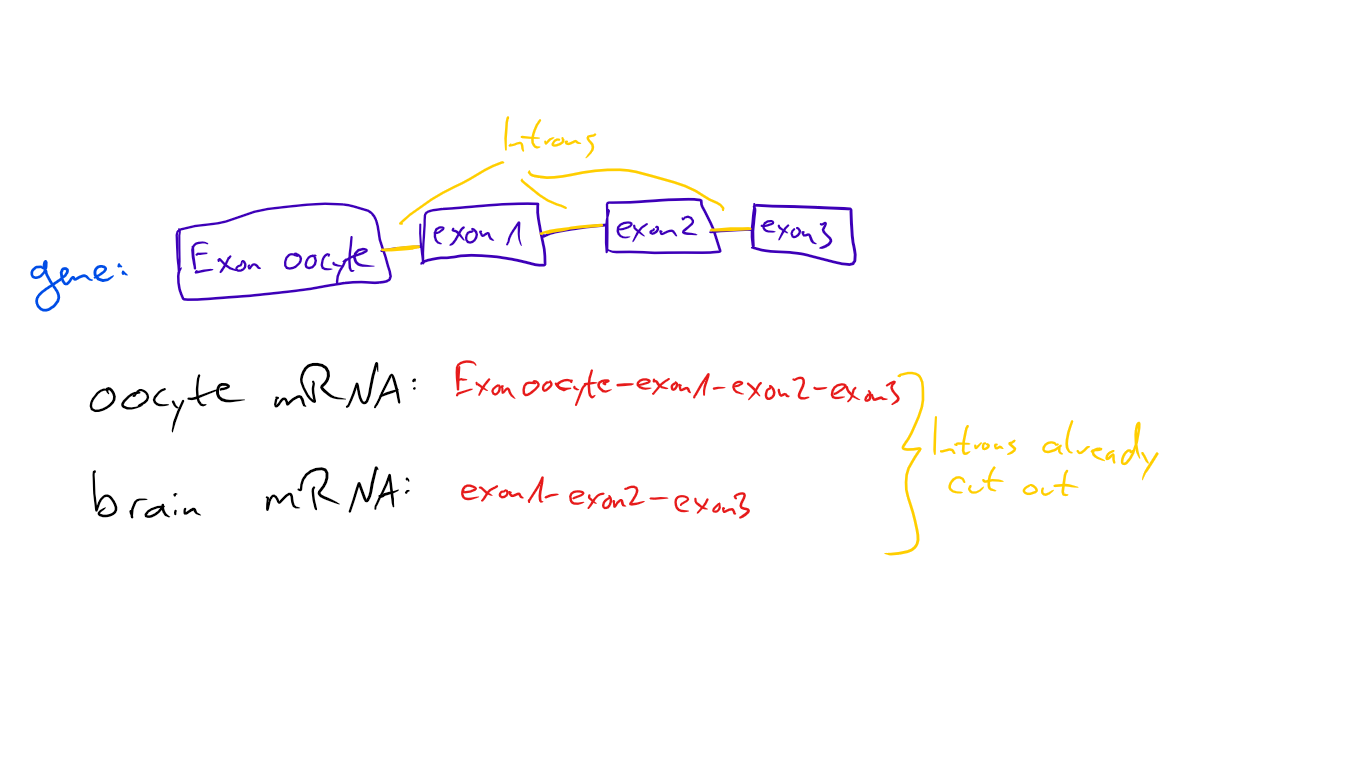

You see, the genetic information isn’t just a long string, it’s divided into “exons” and “introns”. Exons are the parts you actually need, introns the ones that are cut out of the mRNA after the transcription (which is the splicing process!). But not every exon is always an exon and not every intron is always an intron!

Alternative Splicing

Depending on which parts of the gene are deemed exons, you can get a totally different protein out of the whole process. That’s why “more evolved” (technically, there is no such thing as “more evolved” but I have no better expression for this) doesn’t necessarily mean “has more genes” - there can just be more splice variants, which results in a greater amount of available proteins, which in turn creates a more complicated organism.

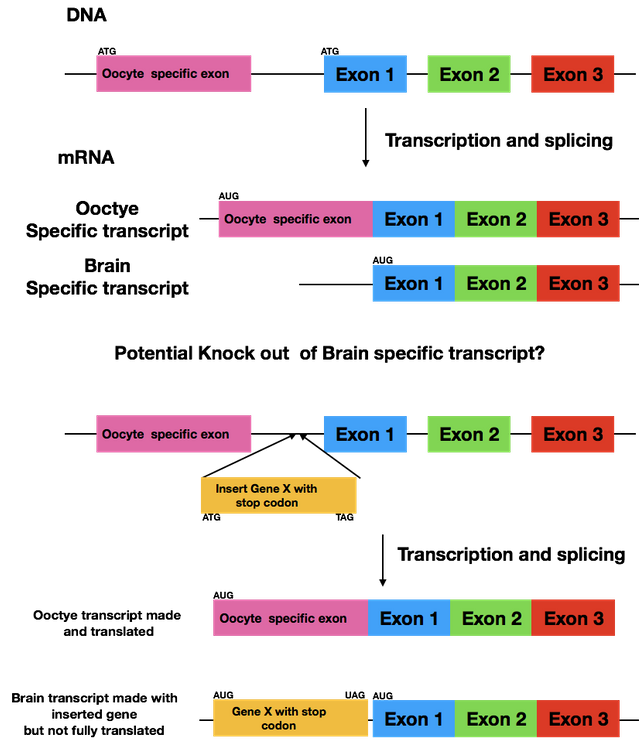

That’s one of the things I’m using for my bachelor thesis research. We’re looking at a gene that’s transcribed in the oocyte (egg cell) and during brain development - but different exons are used each time. If we want to stop the production of one protein but not the other, we need to “destroy” the exact exon that’s only needed in that specific version - but not in the other.

Sounds easy (or not, it’s hard to evaluate how complicated something is if you’ve studied it, so please ask for clarification if you struggle with something specific) but it isn’t, as the exon-usage is basically this:

So we can “turn off” one of these proteins, but not the other! If we try to disrupt the brain-specific protein, we will automatically destroy the oocyte-specific one too, because they share exon 1, 2 and 3 - the brain specific version doesn't have an exon the oocyte-specific version doesn't have too. We do have a strategy to circumvent that, it’s exactly what my thesis will be about and I’ll let you know if I succeed.

The problem with alternative splicing is, that it’s not necessarily something good. There can be diseases because of it when a splicing variant creates a defective gene. Splicing isn’t a perfect process, things can go wrong and cause a mutation in the protein, even if there’s no mutation in the DNA itself.

Of course, there are enzymes that repair this. There are enzymes to repair basically any damages or mistakes that happen in our cells. But it’s a biological system, most things are based on probability. How probable is it that the enzyme finds the damage? Very likely, but sometimes it goes wrong and then you’re sick.

Why on earth am I telling you this?

I might be a bit frustrated by the frequency with which people get “splicing” wrong, might be comparable to a programmer who’s asked to repair a printer … or a microwave, because he’s “good with technology and can do that coding stuff”.

Splicing allows you to get different info from the same genetic sequence and possibly new proteins, but you can’t really “splice together” a fly and an elephant and expect a result.

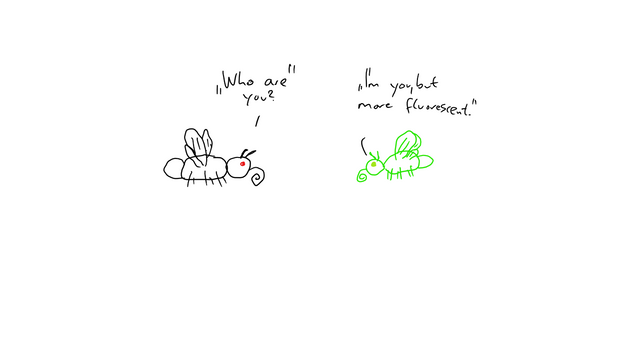

You can, however, take a gene from a jellyfish and make said fly exhibit a green fluorescence. For that, the mRNA transcribed from the gene has to be spliced correctly - but that’d be the case in the jellyfish too. The process with which the gene is introduced into the fly is generally something else.

References:

A genomic view of alternative splicing

Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world

Mechanisms of Alternative Pre-Messenger RNA Splicing

Previously:

All about the Sperm-DNA - Vol. 1

Gene Editing - Cre/loxp - Vol. 2

I have a friend on steemit.chat called mucus or something like that. He's a science expert and I'm sure he can explain to you how DNA splicing works if you have good knives and all.

No but for real, this is an interesting topic and I'm glad for the jellyfish-elephantfly and how it has a pretty glow in the dark.

Weren't you the one painting the bloody clown?

@suesa, I think "splicing" sounds to non-scientists a lot like its non-science usage. When you splice two wires, for example, you join them together into one circuit. So, I can see how someone can form the concept of "splicing together" two animals' DNA to make a hybrid animal. I think movies and TV shows don't help, since sometimes the first time we hear the phrase, it is being misused in the way you're saying.

I relate to this more than you could possibly imagine. I am constantly asked computer hardware and even consumer electronics questions by friends and family. I don't know. I write software. My answer to your question will be as good as Google's and if you ask me to fix something, I will most likely break it. Grr.

But speaking of programming stuff...

Oooh! This reminds me a bit of program execution on computers! It's like the DNA is the program on-disk, and the act of the mRNA copying it is like loading the program into RAM. Then it can undergo changes in state (splicing!) before the output happens (protein!) then it all happens over again from scratch the next time the DNA sequence is loaded.

This is neat stuff! I was always bored in biology class, but I think I was not looking small enough... or fell asleep before we discussed this part. This DNA stuff seems pretty cool :)

There comes the native speaker, I've only ever heard "splicing" in the context of genetics. And yes, I can imagine what you suggested is the reason.

I'm always amused how well certain biological processes can be compared to computer stuff.

And ofc you didn't like it in school, they tend to explain it in a very dry and complicated way - I left out most of the complicated stuff.

"I met a girl, she looks radiant!" :D

"Giiiiiirl, was your father a jellyfish?"

I would like to see the gallery with free hand Drosophila drawings

:D I'm amused by how much you like them

Caenorhabditis is not that expressive, although not bad :D

I mean how else are you going to draw it? xD

In the first year of faculty, we had zoology and we needed to draw what we see on microscope (don't ask why), the assistant critiqued me for not drawing well and I answered:

"I want to make it better, but my hands refuse"

so I have no idea how to make Caenorhabditis different.

I'll try to combine "melted appearance of the dreams" typical for Dali

and the strange eyes typical for Picasso.

And here is my masterpiece:

10+ years later - hands still refuse :D

Burn!

We should make shirts with this for the next SteemStem Meetup! :D

Caenorhabditis piri-formis

I actually remember there are actually a couple of fluorescent animals already? I heard about a rat?

GFP (green fluorescent protein) is used A LOT for research, so yes :)

I was going to make a comment to try to sound smart or something like that but then all the "Caenorhabditis piri-formis" thing just got me.

It was "brilliant" Get it? like a synonymous of fluorescent? no? ok :(

Science people are funny too.

Who would say.

Science people usually just think they're super funny tho

Good article...btw, love the drawings...

Good luck with your research. Are you going to delete the oocyte specific exon using CRISPR?

Cheers!

ian

No, we'll try to deactivate the brain specific protein, which means the oocyte exon is already gone.

The gist is that we will add an additional gene, that will only be transcribed together with the brain-specific protein, which leads to a disruption during the translation. It's a bit difficult to explain in a comment, especially without knowing your biological background.

Oh I see now, you want to specifically inactivate the brain specific transcript without disrupting the oocyte transcripts. So like neuronal specific RNAi to knock down the brain specific transcript.

Yes, but we want to completely knock it out, not just down so RNAi is not an option. We'll be putting a different gene in the untranslated region before exon 1, as this region is not there in the oocyte specific version. This will cause the translation to stop after our artificial gene and the brain specific version will never be translated.

I see. But if you put this gene in between the oocyte exon and exon-1 will it affect how the gene splices, i.e. will the oocyte exon splice to exon-1 with this new gene in there? Although the oocyte transcript spices out that intron and doesn't use it, this new gene could interfere with this process and hence you would also be disrupting the oocyte specific protein function.

i.

Splicing will not be influenced actually. Eukaryotic mRNA is monocistronic (I hope I wrote that correctly, English isn't my first language), which means one mRNA can only lead to one protein. After the protein is done (and there was a stop signal), translation stops - no matter how much mRNA ist left! So the protein we introduced is produced and the one we want to knock out is ignored.

@suesa why not flox the gene of interest you want to knockout, and do tissue specific Cre expression by throwing in an inducible Cre driven by a neuron specific promoter? I guess it depends on what model system you're using

That's a good question, I'd have to ask my supervisor. He's been working on this for a while tho and what you suggested is the traditional way, there's probably a reason why we're not doing it like that. It's mice btw.

Is the neuronal specific transcript due to a difference in transcription initiation start site? I though it was due to alternative splicing. Are you knocking in GFP upstream of exon 1 and having a stop codon before the neuronal specific protein?

@suesa I know this is an older post but I still am curious about how you are knocking out the brain specific transcript. I have made a figure of my understanding form your description. But my question is by inserting the Gene X could this not affect the normal splicing of the oocyte specific message?

Let's say it like this: we hope it doesn't influence the splicing of the oocyte specific version. The untranslated region we're adding the gene to is only found in the brain specific mRNA. If you're curious how it'll turn out, message me July 3rd as that's one day after I've turned in my thesis.

Great post bro this indeed as affected the body of knowledge positively. Great post sir.

Your educational post is very helpful for us. Your contribution in writing really impressed me. Thank you for sharing this post with us.

Did you only comment to upvote yourself? Because this comment is so incredibly generic, it looks a lot like spam. Disgusting.