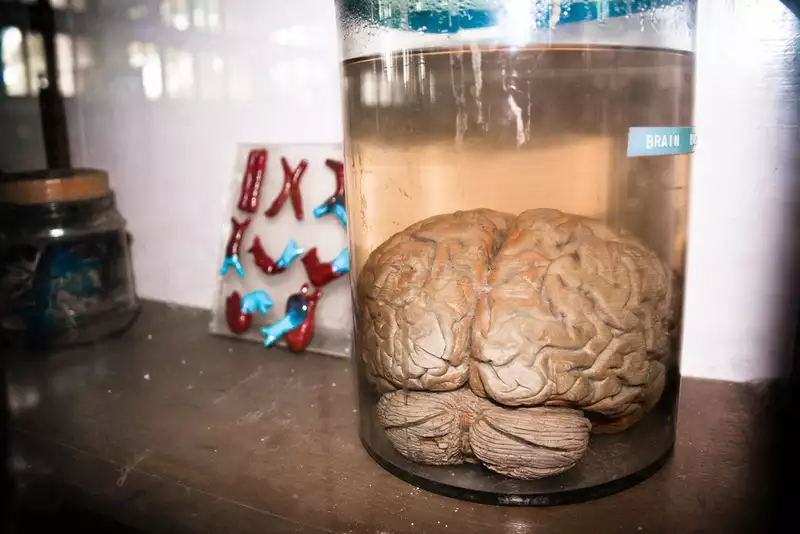

If You Grow A Brain In A Lab, Will It Have A Mind Of Its Own?

As our ability to create organs grow, some unprecedented questions come into play..!

There are a lot of reasons you might want to grow a brain in the lab. For the uninitiated, they would allow us to study neurological issues in detail, which is quite daunting otherwise. Diseases like Alzheimer's and other have devasted millions of people. Therefore, Brain in a jar (so as to speak) could allow us to study disease progression and test medications without requiring to put a real person at stake.

But, there's an ethical problem, the closer we get to growing a human brain, the riskier it becomes.

Given how promising the lab-grown brain would be, it is almost certain we'd be grappling with these questions soon as the dream of growing a brain slowly slips towards reality.

But, for now, all we can do is grow clumps of brain cells— but now is the time to consider ethics.

We already think about brain and life, in in the reverse order. Brain death, in many countries, is considered and the real definition of death. This makes a lot of sense if you think that your life and personalities(Plural) are inside your brain.

So, let's take a moment to consider what would happen if we grew a brain, a real functioning one in the lab! Right now, scientists can create what is known as brain organoids, which are essentially clumps of brain cells. They can grow neurons or other types of cells, but they can’t yet make a functional amalgam of these cells. Your brain contains billions of neurons that rely on many millions of other kinds of cells, like glia and astrocytes. Scientists haven’t figured out a way to get all those different groups to grow together in something resembling a real brain. Someday, though, they will.

Considering that the brain has been made, let's take a look at some potential questions !?

- Could a lab-grown brain become a real human?

Many of the other researchers didn’t think a lab-grown brain would ever become a person. James Bernat, a professor of neurology and medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, says “I do not think scientists will ever develop a lab-grown brain organoid that would have enough neurological function to be considered a person.” Though he also noted that “whether brain organoids of the future will ever develop neurological functions is highly questionable.”

Jeantine Lunshof, a research scientist-ethicist at MIT Media Lab, says “I do not think that an isolated lab-grown brain can ever become a 'person.'” Personhood, she argues, is a challenging concept. “Personhood presupposes capabilities and—to the best of my current knowledge—an isolated brain that has been grown from an organoid will always lack that,” she says.

Similarly, Eswar Iyer, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School, says he doesn’t think lab-grown neural tissue would have the right attributes to be considered a person. “Artificial intelligence may be ahead in line for this.”

- Will we be able to know when or if a brain is conscious?

There’s no singular, scientific definition of “consciousness.” We know humans have it. We are aware of our own existence and our place in the world, and we have our own inner thoughts and feelings. Other animals? We’re not so sure.

Nita Farahany, director of the Duke Initiative for Science & Society, notes that we already “are able to detect when there is a loss of consciousness in humans.” But she says it will be challenging to understand whether other species have consciousness, or which ones have the capacity to develop it.

There’s a gray area here, though Stanford’s Greely argues we don’t necessarily have to pin down the answers to the whole spectrum of possibilities. “I think we’ll be to agree on some ‘safe harbors’ where it clearly is or isn’t conscious without necessarily being able to answer it all cases. We know that a human body that has been cold, blue, and stiff for two days is not a seat of consciousness; we know that an academic writing email answers to questions (probably) is. How big will be the area between ‘comfortable’ extremes? That remains to be seen.”

But maybe we’ll never need to worry about it. James Bernat doesn’t think so. “In our lifetimes, I do not think we will need to consider the question of when a lab-grown brain organoid is conscious,” he says, “because I don’t think we will understand how the brain generates consciousness for the foreseeable future. Measuring it represents another challenge that might be possible if we can ever fully understand its precise biological mechanism.”

MIT’s Lunshof says that it might not even be possible. “With isolated lab-grown organoids, there never has been anything like 'consciousness' and I do not see how it would acquire it, in particular as it is without sensory organs. On the other hand, experiments have shown reactivity (electrical current) to e.g. light. But, that is not consciousness.”

“I do believe we do need more explicit definitions of what consciousness is, together with more developed guidelines on how to recognize and measure indications of consciousness in the laboratory setting,” says Jonathan Ting, an assistant investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science. “The answers to these emerging and difficult questions may be slow to come, but our intent is to stimulate thought and open a healthy dialogue about the ethical considerations as we enter new uncharted territory in human brain research.”

Greely agrees. “This paper reflects some of the most interesting, and perplexing, issues I’ve encountered in over a quarter of a century working in this field. It’s exciting to deal with them—and comforting that, at this point anyway, we seem to be years if not decades away from having to face them in their most serious forms.”

Which is not to say we should put off having the discussion. However far away this hypothetical future may be, Greely says it’s important to begin now. “We have time to think about them. We need to start doing so. And that’s what the neuroscience and ethics authors of this piece all agree about.”

Rohan Jain