Lunar eclipse report by Sky and Telescope(red and blue moon)

A total lunar eclipse, though less dramatic than a solar eclipse, is nevertheless a sight to behold. The full Moon (total lunar eclipses by definition can only occur when the Moon is full) gradually darkens, then turns a smoldering coppery color. The total lunar eclipse of January 31, 2018, garnered a lot of attention since it was the second full Moon of the month, and the Moon had just passed perigee the day before, engendering higher-than-usual tides in coastal areas.

But the latter two points did not distract from the wonder of the phenomenon itself: Three celestial bodies are aligned in such a way that one body blocks the light from another. It’s straightforward physics, as is the fact that the surface of the Moon turns that reddish or orange-ish color due to the refraction of the light from the Sun by the Earth’s atmosphere. Witnessing a lunar eclipse is witnessing physics – and astronomy – in action.

Of those lucky enough to live in the zones of totality in continental North America, some got out of bed very early in the morning (or stayed up very late) and went outside to turn their gaze skyward. (The staff of Sky & Telescope had a less than stellar view from the East Coast, but we're looking forward to the next total lunar eclipse visible all across Northern America just a year from now, in January 2019.)

Viewers from Canada to Arizona and all the way across the Pacific to China sent in reports of the total lunar eclipse. Some simply stepped out into their backyards, while others, like Jeff Dai, shared the experience with many more: “Millions of people in Chongqing went outdoors to enjoy this beautiful celestial view.” Some enjoyed balmy weather under clear skies, while others, like Bruce McCurdy in Alberta observed the lunar eclipse through patchy cloud in temperatures down to -23°C (-9°F) with a wind chill of -34°C (-29°F).

Sky & Telescope’s Contributing Editor Alan Whitman, from his prime viewing spot in British Columbia, noted that, “This was another very bright orange total lunar eclipse. Even at mid-eclipse the Moon was about three magnitudes brighter than Pollux.”

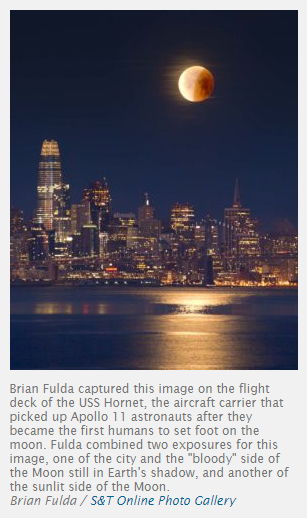

Viewers in California had a different experience. Hiram in Santa Cruz observed what “… looked like a very dark eclipse,” and Robert Garfinkle writes, “It was a very dark reddish total lunar eclipse here in the San Francisco Bay Area.”

How can the same phenomenon be described as both “bright” and “dark” at the same time by observers on the western coast? Terry Moseley, replying to comments on the Solar Eclipse Mailing List, explains, “The appearance could depend on the amount of light pollution. In a brightly lit city, a total lunar eclipse could appear quite dark, even if it was bright on the Danjon scale. But in a dark sky, it might appear relatively bright.”

Apart from notes on brightness, what other details did viewers observe?

Alan Whitman saw “… a bright yellow-white rim on the Moon’s southern limb although it became very thin at mid-totality,” and “…the northern limb, deepest into the umbra, was orange, not red.”

In the San Francisco Bay Area, Robert Garfinkle noted that “… during totality, the western half (Grimaldi side) disappeared from my view,” while Alan Whitman states that “… Grimaldi was prominent within the brighter edge of the umbra…” He goes on to say that “… the bright rays around Copernicus, Kepler, and Aristarchus were all prominent, but not the craters themselves.”

To give you an idea of the difference in illumination between pre-eclipse moonlight and during the eclipse, Robert Garfinkle writes, “Before the eclipse began, my backyard was so bright it was as if I had some low-wattage lights on. By the time the umbral portion of the eclipse had covered only part of Oceanus Procellarum the ‘lights’ went out and my backyard was dark like on a new Moon night.”