Zen and Meditation

A century ago, psychologists and other scientists struggled to realize how meditation practice benefited the mind or the body. The main picture was far from being accomplished. Luckily, we were graced with the existence of Carl Gustav Jung, who not only deciphered archetypes and the collective unconscious (among so many other concepts) but also gave a rather accurate description of how the meditation process helps us achieve a better understanding of ourselves and our environment.He determined that everyone had “disposable” psychic energy, whose latent powers lay dormant in the unconscious, and there they will be used in order to manage each and every conflict our mind and brain determine as such. Now, the interesting part is what happens when conflicts are solved. Then this psychic energy could be liberated and rechanneled, improving and boosting mental processes and functions.

MEDITATION AT THE LAB

In 1980 some scientists already had a glimpse of the specific mechanisms of how this is accomplished, Dr. Deane Shapiro mentioned that with the removal or minimization of cognitive stimuli and generally increasing awareness, meditation can influence both the quality (accuracy) and quantity (detection) of perception. And Brown, Forte and Dysart also point to this as a possible explanation for the phenomenon: “[the higher rate of detection of single light flashes] involves quieting some of the higher mental processes which normally obstruct the perception of subtle events.”

Until not so far ago, meditation was an implicitly forbidden subject of scientific research. The underlying and usually hidden philosophical assumptions of traditional, rationalist science do not value the intuitive. They do not acknowledge the reality of the transcendent or subscribe to the concept of higher states of consciousness. Not properly acknowledging this fact, we are neglecting our own core.

That being said, meditation techniques have been difficult to measure. A key hindrance that makes any subject of study regarding this area or any other involving mind or consciousness is the fact that our individual brains show different psychophysiological responses, or that religious experiences affect individuals in different ways. As Jung said: It is not that something different is seen, but that one sees differently.

It is as though the spatial act of seeing was changed by a new dimension.So, a given range of stimuli does arouse some persons more than others. The same input has different reaction depending on each one of us. There also are clear differences in brain function among different personality types. In one EEG study, realized by K. Thatcher, W. Wiederholt, and R. Fischer, the baseline brain waves of subjects classified as extroverts were higher in amplitude than those of the introverts.

Existing research on meditation has other limitations. One is crucial: no physiological or biochemical measurements can define the precise subjective quality of the meditator’s private state of awareness at any one moment, let alone sequentially.

But from now on all is good news. There are lots of scientific studies towards meditation. Many reviews have now clarified what kinds of changes meditation produces in the body. The consensus: meditation causes secondary physiological and biochemical changes that are appropriate to how much relaxation is involved.

Dr. Deane H. Shapiro is Professor Emeritus of the Psychiatry & Human Behavior School of Medicine, at Stanford University. His research involved developing a theory of human control, a psychological test to measure a person’s control profile (the Shapiro Control Inventory Manual), and a specific therapeutic approach (Control Therapy) to match the most effective strategies to a person’s particular control profile. So, among his many pages and pages of research, now I will just focus on his findings regarding brain plasticity on meditation subjects, and these findings are:

- changes in the bioelectrical brain pattern

- metabolic activation of specific brain areas

- cognitive functions supported by idiosyncratic neural networks, and

- neuroimaging studies showing measurable increases in several brain structures.

This is another scientist that has proven how meditation literally changes and shifts the brain.

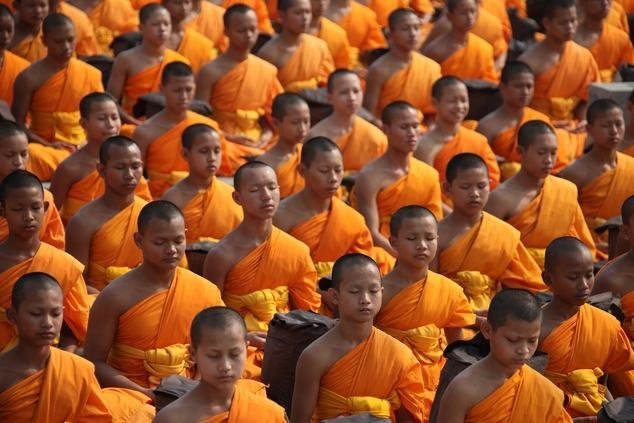

ZEN AND BUDDHISM

The early Indian Buddhists summarized their meditative approach back in the fifth century. One general pathway was the direct route of insight meditation, Vipassana. The other was the route of calming meditation, Samatha. The latter began with a calm serenity, developed into one-pointed concentration, and finally shifted into the full meditative absorptions of samadhi.Embedded in the word Zen is the story of how it evolved over the centuries. Its meditative techniques stemmed from ancient yoga practices. At that time, in India, the Sanskrit word for meditation was dhyana. This evolved into the phrase Ch’an-Na, then into the Chinese word Ch’an. Later, Buddhist monks transplanted this Ch’an form of meditation to Japan, where the Japanese pronounced it Zen.

Zen, then, stands for the school of Buddhism that emphasized meditation and that evolved further as it spread from India to China, and to Japan. Zazen is its system of meditation. Zen is a comprehensive Way of spiritual development, one of its effects are brain modifications through the detection and shift of mind processes, therefore literally reshaping the anatomy of the brain. Controlling the mind we can customize the way our brain perceives things, and as default it always drives this perception towards a clearer understanding of ourselves and others.

Zen uses various approaches to reshape the input to the Ego, to defuse it, and to redeploy its output.

Master Dogen also commented on the several steps through which the aspirant passed on the long road to experiencing the objective world. The steps begin, he said, in the quiet meditative context of no-thought, and then proceed to the letting go of self. In Zen, the brain resolves an existential impasse. In this context, one calls it “enlightenment” or “awakening,” kensho or satori. It is also termed “insight wisdom” or “seeing into one’s true nature.” The two intuitive processes are similar in form if not in content and degree. The Zen meditative way presents several potential advantages. It proceeds very slowly, voluntarily, legally. It acts spontaneously from the inside, discretely. Overall, the meditative mental landscape is much calmer, clearer. Nerve cells will have been liberated from much of their usual irrelevant synaptic clutter. Dr. James Austin emphasizes the shift in terms of respiration, where experienced monks have somehow longer expiration periods, also needing less volume of oxygen per minute. Whenever we breathe more quietly and prolong the phase of expiration, we are probably quieting the firing activity of many nerve cells, both in the medulla and above. Buddhist meditative chants are themselves associated with enhanced, rhythmic, synchronous theta activity. The theta range is associated with recall, fantasy, imagery, creativity, planning, dreaming, switching thoughts, deep meditation, drowsiness, access to subconscious images, reduced blood pressure, and more.

CONCLUSION

There exists so much information implying that meditation techniques enhance the so-called Relaxation Response. It’s clear that the practice of meditation literally raises awareness, well-being and several physiologic markers linked to a hypometabolic state of combined physical relaxation and mental awareness. Finally, and perhaps most important from the standpoint of basic science, the investigation has moved from the level of gross physiology to more detailed points of biochemistry and the voluntary control of internal states. From a philosophical standpoint, these studies have also raised a number of issues about the role of spiritual experiences in both psychology and medicine.

It took me a long time to understand why Buddhists say that when you meditate you do it not only for your own sake, but also for the sake of all living beings……to me it seemed so new-age. I mean, in what way will the planet be better if I sit for 30 minutes? Now I realize that one should only start working on oneself, and then afterwards can achieve working for and helping others. Also, if I am peaceful and calm (which happens generally when doing active meditation) the people around me feel that, even though sometimes they can’t express it, and if along me there is someone else that also has this characteristic, then the effect is stronger, and so on and so forth.

On a personal basis, the self-knowledge permits the sense and comprehension of the energetic biofields that come from the body and surround it. Those biofields have a great relationship with the consciousness and the awareness of the biofields is linked to the quality of that consciousness. There exist many studies where Group Meditation alters the community’s accidents or crime statistics. These studies are specially made by the Transcendental Meditation community, which is actively and profusely doing research on the subject to bring evidence of its benefits.

To conclude, it is my own belief that, at personal level, there are various ways that lead towards self-knowledge and development of self, and at global level, there are various ways that lead towards peace. But only one highway for both of them. Meditation is the highway. It has always been and despite the awesome technologic improvements, probably will always be.