Supermassive Black Hole seen eating a star for the first time

Scientists have seen the vast blast thrown out by a black hole eating a star for the first ever time.

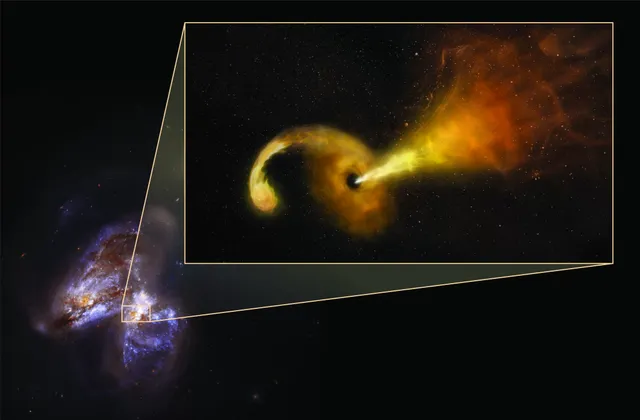

Researchers have finally watched the formation and expansion of the fast-moving jet of material that is thrown out when a supermassive black hole's gravity grabs a star and tears it apart.

Scientists watched the dramatic event using highly specialised telescopes, which are trained on a pair of colliding galaxies called Arp 299, nearly 150 million light-years from Earth. At the centre of one of those galaxies, a star twice the size of the Sun came too close to a black hole that is more than 20 million times big as our Sun – and was shredded apart, throwing a blast across the universe.

It was that blast that scientists were able to see happen for the first time ever. Theorists have long thought the events were common – speculating that material torn from the star makes a rotating disk around the black hole, emitting intense X-rays and visible light, and also pushes jets of material outward from the poles of the disk at nearly the speed of light – but have been yet to see it actually happen.

Supermassive black holes that are millions to billions times the mass of the sun are thought to lurk in the hearts of most, if not all, large galaxies. If a star passes too close to such a monstrous black hole, its powerful gravitational pull will tear it apart in a so-called tidal disruption event.

As a black hole tears matter off a star, this material forms a rotating disk that glows brightly before it falls into the black hole. Previous research also suggested that jets of particles are launched outward from the poles of these so-called accretion disks at extraordinarily high speeds.

Most times, supermassive black holes are not actively devouring anything.

The small number of tidal disruption events that astronomers have detected so far offer scientists the chance to learn more about the formation and evolution of these jets.

These new findings suggest that infrared and radio telescopes may discover many tidal disruption events that may have escaped detection until now because dust absorbed any visible light from them, Pérez-Torres said. Such events may have been more common in the early universe, so investigating them may help scientists understand the newborn cosmos, the researchers added.

✅ @dverekar, I gave you an upvote on your first post! Please give me a follow and I will give you a follow in return!

Please also take a moment to read this post regarding bad behavior on Steemit.