Fossil turtle didn't have a shell yet, but had the first toothless turtle beak

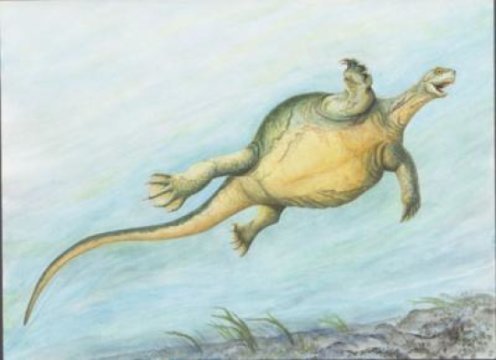

"This animal was more than six feet long, it had an abnormal plate like body and a long tail, and the front piece of its jaws formed into this unusual snout," says Olivier Rieppel, a scientist at Chicago's Field Museum and one of the creators of another paper in Nature. "It most likely lived in shallow water and dove in the mud for sustenance."

-----------------

The new species has been dedicated Eorhynchochelys sinensis - a sizable chunk, however with a direct significance. Eorhynchochelys ("Ay-goodness arena gracious bottom is") signifies "day break mouth turtle" - basically, first turtle with a nose - while sinensis, signifying "from China," alludes to where it was found by the investigation's lead creator, Li Chun of China's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.

Eorhynchochelys isn't the main sort of early turtle that researchers have found - there is another early turtle with a fractional shell however no mouth. Up to this point, it's been vague how they all fit into the reptile family tree. "The birthplace of turtles has been an unsolved issue in fossil science for a long time," says Rieppel. "Presently with Eorhynchochelys, how turtles developed has turned into a ton clearer."

The way that Eorhynchochelys built up a snout before other early turtles yet didn't have a shell is proof of mosaic advancement - the possibility that attributes can advance freely from each other and at an alternate rate, and that only one out of every odd hereditary species has a similar blend of these characteristics. Present day turtles have the two shells and bills, yet the way development took to arrive was certainly not a straight line. Rather, some turtle relatives got fractional shells while others got snouts, and in the long run, the hereditary changes that make these characteristics happened in a similar creature.

"This astonishingly huge fossil is an extremely energizing revelation giving us another piece in the perplex of turtle advancement," says Nick Fraser, a creator of the examination from National Museums Scotland. "It demonstrates that early turtle development was not a direct, well ordered amassing of one of a kind qualities yet was a substantially more mind boggling arrangement of occasions that we are just barely starting to unwind."

Fine points of interest in the skull of Eorhynchochelys illuminated another turtle advancement puzzle. For quite a long time, researchers didn't know whether turtle predecessors were a piece of a similar reptile assemble as current reptiles and snakes - diapsids, which from the get-go in their advancement had two gaps on the sides of their skulls - or on the off chance that they were anapsids that do not have these openings. Eorhynchochelys' skull gives hints that it was a diapsid. "With Eorhynchochelys' diapsid skull, we realize that turtles are not identified with the early anapsid reptiles, but rather are rather identified with developmentally further developed diapsid reptiles. This is solidified, the discussion is finished," says Rieppel.

The examination's creators say that their discoveries, both about how and when turtles created shells and their status as diapsids, will change how researchers consider this branch of creatures. "I was astounded myself," says Rieppel. "Eorhynchochelys influences the turtle family to tree bode well. Until the point that I saw this fossil, I didn't get a portion of its relatives as turtles. Presently, I do."

This examination was added to by Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, the CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, National Museums Scotland, the Field Museum, and the Canadian Museum of Nature.