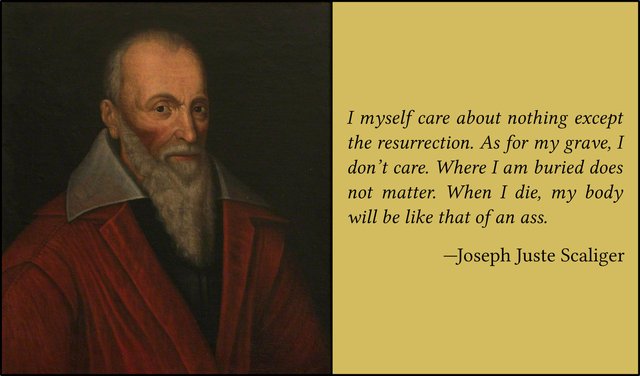

Scaliger’s Final Years

After devoting a lifetime to the highest flights of scholarship, Joseph Juste Scaliger must have expected that he would be allowed to retire in peace and enjoy his hard-earned laurels. Such, however, was not to be his fate. The Catholic prelates who had been hounding him relentlessly ever since he had proclaimed himself a Calvinist were determined to pursue him to the grave and bury his reputation along with his body. Their final assault would be the most devastating:

Even before the Thesaurus left Scaliger’s hands [in 1606], moreover, his enemies had begun to attack his social as well as his intellectual position. The trouble began from his early, formative wound: the false claim to nobility that his father had bequeathed to him. This had long attracted derision in some Italian circles. As early as 1573 the younger Agostino Nifo [nephew of the Italian philosopher Agostino Nifo] told de Thou, in Padua, that Scaliger was really a mere Bordon. After [Scaliger’s edition of the works of Sextus Pompeius Festus] appeared [in 1574–75] ... Scaliger’s Paduan enemies made public what remains the central document that disproves Julius Caesar’s stories, his doctoral diploma. Scaliger’s pseudonymous attack on Roberto Titi brought these matters out into the harsh light of print, as Titi threatened in his Assertio of 1589 to ‛tear off Scaliger’s mask’ of nobility and reveal him for what he was. And Scaliger’s proud and defensive Epistola on his family impressed his friends but failed to silence his literary foes. ―Grafton 745

In the vanguard of his literary foes were two Jesuit scholars, Carolus Scribani and Caspar Schoppe. Scribani was a Belgian priest of Italian extraction. He was a prolific author of polemical texts directed against Calvinism, which was then rampant in the Low Countries. Schoppe was born to Protestant parents in the Upper Palatinate but converted to Catholicism in his twenties. As a Protestant he had been an admirer of Scaliger, but as a Catholic he unleashed upon him all the fanaticism of the convert.

In 1605 Scribani dealt the first hammer blow to Scaliger’s reputation with his Amphitheatrum Honoris, a diatribe of insults levelled at Scaliger and other Calvinists. It speaks volumes that this work was published under a pseudonym: Clarus Bonarscius. Anthony Grafton characterizes it as:

... a work so empty of content and vicious in tone as to make Possevino’s Apparatus sacer resemble a piece of serious scholarship. Scribani took advantage of every fact, factoid, and rumour he could to defame Scaliger, repeatedly insisting on his low birth and trying to isolate him from Catholic scholars who had shown him sympathy and respect in the past. ―Grafton 746

If Scribani’s chosen weapon was the maul, Schoppe wielded the scalpel―but with no less vituperation:

In 1607 [Caspar Schoppe], then in the service of the Jesuits, whom he afterwards so bitterly libelled, published his Scaliger hypobolimaeus (“The Supposititious Scaliger”), a quarto volume of more than four hundred pages, written with consummate ability, in an admirable and incisive style, with the entire disregard for truth which [Schoppe] always displayed, and with all the power of his accomplished sarcasm. Every piece of scandal which could be raked together respecting Scaliger or his family is to be found there. The author professes to point out five hundred lies in the Epistola de vetustate of Scaliger, but the main argument of the book is to show the falsity of his pretensions to be of the family of La Scala, and of the narrative of his father’s early life. “No stronger proof,” says Mark Pattison, “can be given of the impressions produced by this powerful philippic, dedicated to the defamation of an individual, than that it has been the source from which the biography of Scaliger, as it now stands in our biographical collections, has mainly flowed.” (Chisholm 285 : Pattison 191–192)

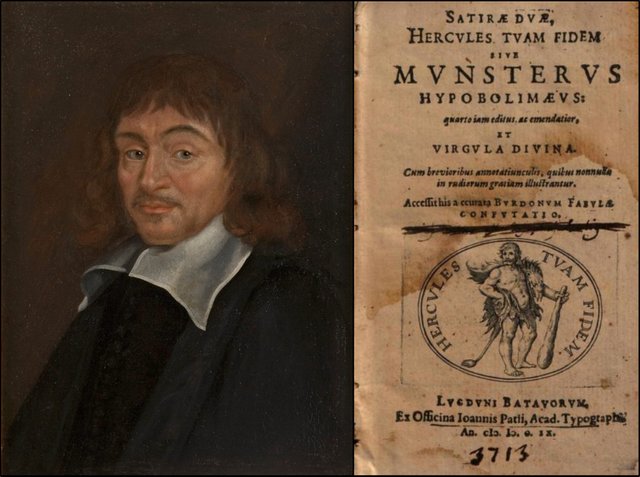

An indignant Scaliger published a pseudonymous riposte to Schoppe’s attack. The Confutatio Fabulae Burdonum [A Refutation of the Asses’ Fables] of 1608 was his last published work. His pupil and friend Daniël Heinsius also came to his defence with a pair of satires entitled Hercules tuam fidem [Help Me, Hercules!], in which he repaid Schoppe in his own coin. Scaliger’s Confutio was published as an appendix to Heinsius’s two satires under the pseudonym I R Batavo, Iuris Studioso [By I R, Dutch Law Student]. Scaliger borrowed the initials from his nineteen-year-old pupil Janus Rutgersius (Bernays 214).

Scaliger claimed that the diploma which supposedly proved that his father was a commoner called Giulio Bordone actually belonged to another man of that name, a son of the artist and cartographer Benedetto Bordone. He also reminded his readers that a succession of famous French and Italian scholars―among them Onofrio Panvinio, Marc Antoine Muret, and Paolo Manuzio―had all acknowledged his noble pedigree. But the damage was done. Although his Protestant friends remained loyal, many Catholic scholars distanced themselves from him, and even those who continued to support him had to admit that he had no claim to the purple. He was, after all, a man of low birth. Scribani and Schoppe had done their job well. Scaliger’s reputation would not recover from these blows for over two centuries.

Scaliger was a broken man. His health declined when he was obliged to move from his comfortable lodgings on Leiden’s Breestraat, where he had resided for over ten years (de Jonge 81). His landlady, Marie van den Bergh, wished to sell the house. Scaliger moved to a house on Kerkgracht Street, though it is not known whether this was Pieterskerkgracht or Hooglandse Kerkgracht (de Jonge 87). These two streets are about 500 m apart, on opposite sides of the New Rhine.

His new house was small and damp. Nevertheless, he continued to work, revising the Thesaurus Temporum and copying all the material in foreign languages from his personal library. He continued to take an interest in the affairs of Leiden University. When he learnt of a rumour that he had died in Prague, his response was:

I do not suppose ... that it makes any great difference to me whether I am dead somewhere else, so long as I am alive here. ―Grafton 749–750 : Robinson 53

The winter of 1607–08 was one of the coldest of the Little Ice Age. Scaliger survived it, but his health never recovered from the blow. Plans to collaborate with Heinsius on a new edition of the works of the ancient Roman dramatist Plautus had to be abandoned, and by November 1608 he was so ill that he made his will (Grafton 749–750).

Joseph Juste Scaliger died of dropsy in Leiden on 21 January 1609. He was sixty-eight years of age. Four days later he was buried in the Vrouwekerk (Church of Our Lady), a Huguenot church in the centre of Leiden, of which only a few ruins remain. Since 1584 the church had served Leiden’s Walloon community. The position of Scaliger’s grave in the north transept was later marked by a gravestone on which were carved the Scaliger coat of arms and the words (in Dutch): Here I Await the Resurrection (de Jonge 87–88).

In 1819, when the Vrouwekerk was demolished, Scaliger’s remains were transferred to the Pieterskerk, a few hundred metres away.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 24, Pages 284–286, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1911)

- Pierre Desmaizeaux (editor), Scaligerana, Thuana, Perroniana, Pithoeana, et Columesiana, Volume 2, Prima Scaligerana, Secunda Scaligerana, Covens & Mortier, Amsterdam (1740)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 2, Historical Chronology, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993)

- Henk Jan de Jonge, Josephus Scaliger in Leiden, Jaarboekje voor geschiedenis en oudheidkunde van Leiden en Omstreken, Volume 71, Pages 71–94, Beugelsdijk, Leiden (1979)

- Philippe Tamizey de Larroque (editor), Lettres Françaises Inédites de Joseph Scaliger, Alphonse Picard, Paris (1884)

- Mark Pattison, Joseph Scaliger, Essays, Volume 1, Pages 132–243, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1889)

- George W Robinson (translator), Autobiography of Joseph Scaliger: With Autobiographical Selections from His Letters, His Testament and the Funeral Orations by Daniel Heinsius and Dominicus Baudius, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1927)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Epistola de Vetustate et Splendore Gentis Scaligerae et Iulii Caesari Scaligeri Vita [Epistle on the Antiquity and Splendour of the Scaliger Family, and The Life Julius Caesar Scaliger], Franciscus Raphelengius, Leiden (1594)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Confutatio Fabulae Burdonum, in Daniel Heinsius, Two Satires: Help Me, Hercules! Or, The Illegitimate Münsterian, Appendix (Pages 159–441), Joseph Scaliger, A Confutation of the Silly Fable of the Asses, Johannes Patius, Leiden (1609)

- Carolus Scribani, Amphitheatrum Honoris, Second Edition, Alexander Verheyden, Antwerp (1606)

- Caspar Schoppe, Scaliger Hypobolimaeus, Johann Albin, Mainz (1607)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Anonymous Portrait, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Public Domain

- Charles Scribani: Anthony van Dyck (artist), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Public Domain

- Caspar Schoppe: Portrait of Kaspar Schoppius (cropped), Peter Paul Rubens (artist), Palatine Gallery, Pitti Palace, Florence, Public Domain

- Daniel Heinsius: Anonymous Portrait, Gripsholm Castle, Sweden, Public Domain

- The Ruins of the Vrouwekerk, Leiden: Jvhertum (photographer), Public Domain

- Scaliger’s Epitaph and the Pieterskerk, Leiden: © Pieterskerk Leiden, Fair Use