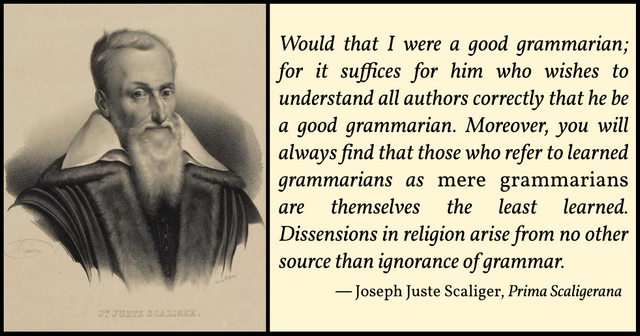

Joseph Juste Scaliger in Geneva

In the last article in this series, we saw how Joseph Juste Scaliger completed his edition of the Appendix Vergiliana at Lyon, scribbling a pair of dedications before handing the manuscript over to the printer Guillaume Rouillé on 22 August 1572. He then left for Strasbourg, where he was due to meet up with Jean de Monluc, Bishop of Valence, who had been dispatched by Catherine de’ Medici to secure the throne of Poland for her son, the Duke of Anjou. Scaliger’s journey took him through Switzerland. On the night of 23-24 August, he was asleep in Lausanne when the infamous St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre shook Paris. More than a thousand Protestant Huguenots—historians still debate the exact number—were murdered by Catholic extremists. It is possible that Catherine, who instigated the massacre, had sent the irenic Monluc on his embassy to Poland to prevent him from interfering with her nefarious plans.

Scaliger did not learn of the catastrophe until he reached Strasbourg. As a Huguenot, he must have feared for his life should he return to France. He abandoned his plans to wait for Monluc and fled instead to the Calvinist city of Geneva, where he was welcomed by Théodore de Bèze, the spiritual leader of the Republic of Geneva and the successor of Jean Calvin:

Apparently he arrived there on September 8, as the Book of the Inhabitants of Geneva reports: “Joseph de La Scale, of Agen in Agenois, gentleman, as attested by M. de Bèze. (Ledegang-Keegstra 442)

Scaliger was already acquainted with de Bèze, as a number of intimate letters between the two men survive, but the exact date and circumstances of their first meeting are still unknown (Ledegang-Keegstra 441-442). The appearance of Scaliger’s name in Geneva’s Livre des Inhabitants means that he was quickly enrolled as a citizen of the Republic (Grafton 124).

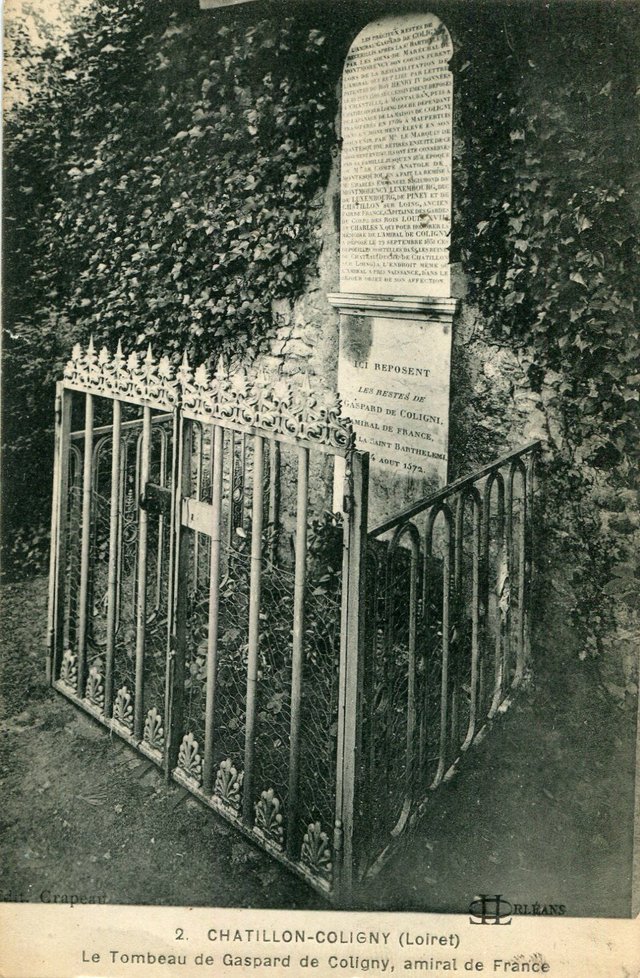

Scaliger immediate response to the massacre was literary: he composed a fiery epitaph to the memory of Gaspard II de Coligny, the Huguenot leader, who was one of the first victims of the pogrom:

Scaliger might no longer have felt inclined to serve diplomatically in a government that treated his co-religionists in such a manner; he vented his indignation at the murder of Coligny and the desecration of his corpse in verse, the publication of which the not too timid Beza thwarted, probably on account of its vituperativeness [Heftigkeit]. (Bernays 42. See also Ledegang-Keegstra 443)

In an endnote, Bernays admits that the failure to publish the inflammatory verses may have been due to simple negligence—an oversight on Beza’s part, rather than the diplomatic suppression of incendiary material. In 1606, Scaliger was commissioned by de Coligny’s daughter to draft a Latin epitaph for his tomb at the Château de Châtillon-Coligny, but even this was too vehement to be used without alteration (Bernays 150 : d’Aubigné 2:4:541-545). (This tomb no longer exists. Coligny’s simple grave at Châtillon-Coligny dates from 1851 and does not bear Scaliger’s epitaph.)

Scaliger remained in Geneva for two years (1572-74). On 31 October he was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the Calvinistic Academy—a post he accepted only reluctantly. Over the course of the following two years, he delivered lectures in the Academy’s schola publica on Aristotle’s Organon and Cicero’s dialogue De finibus bonorum et malorum. But the life of a professor did not appeal to him. Scaliger’s passion was ever to learn, not to teach. He would eventually return to France via Basle in the late summer of 1574, following the conclusion of the Fourth War of the Huguenots, and he would spend most of the following twenty years—1574-1593—in the service of his patron Louis Chasteigner de la Roche-Posay.

Among the scholars with whom Scaliger became acquainted in Geneva was the Scottish theologian Andrew Melville, Professor of Humanity at the Academy. A close friendship grew up between the two exiles, despite the fact that Melville had fought against the Huguenots at the Siege of Poitiers in 1569. Scaliger’s later works on ancient calendars greatly influenced Melville’s views on sacred chronology, while Melville for his part suggested some textual emendations to one of Scaliger’s Latin editions, Marcus Manilius’s Astronomica. He also provided some introductory poems for an edition of the poems of Scaliger’s father Julius Caesar Scaliger (Grafton 126).

During his two years in Geneva Scaliger also developed a working relationship with the French printer and classical scholar Henri II Estienne, who ran the Republic’s most important printing press:

Like everyone else, he found Estienne personally exasperating, particularly because of his deplorable habit of altering the books he accepted for publication without telling their authors that he had done so. Nevertheless he supplied Estienne with advice and brief critical appendices for his collection of the fragments of the pre-Socratics and for an anthology of Greek works bearing on the life of Homer. And he provided translations of a number of epigrams from the Greek Anthology to accompany Estienne’s panegyric on the Frankfurt book-fair, the Francofordiense Emporium of 1574. (Grafton 127)

In addition to delivering public lectures, Scaliger also took on private students, such as the future President of the Parlement de Normandie Claude Groulart. Goulart had studied with Jacques Cujas in Valence at the same time as Scaliger. In Geneva, he studied Greek and Latin for fifteen months under Scaliger’s tutelage. Groulart would later write that he learned more from Scaliger in one month than he did from other tutors in one year.

Homerica

The two years Scaliger spent at Geneva marked an important turning point in his career:

The Geneva period was critical for the development of Scaliger’s mind ... In Geneva he had time to reflect; and, very gradually, contact with the jurists began to change the main direction of his work. (Grafton 124 ... 126)

The new direction Grafton speaks of would gradually steer Scaliger away from Classical poetry and drama—“literature”—and towards more technical subjects of late antiquity, such as grammar, chronology, and calendrics. The fruits of this new direction, however, would take time to mature, for, despite his onerous duties as a public lecturer and private tutor, Scaliger continued to pursue his interests in classical philology. After disposing of the Appendix Vergiliana, he initially turned his attention to the Astronomica of Marcus Manilius:

Beginning to study Manilius, he discovered that the text suffered from numerous corruptions and, in particular, from transpositions of lines and passages. He set out to correct these in an edition of and commentary on the text. (Grafton 127)

Marcus Manilius was a Roman poet and astrologer of the 1st century CE. He is remembered solely for his unfinished didactic poem Astronomica.

About seven years would elapse before Scaliger’s edition of Manilius was ready for the printer. In the intervening time, he successfully completed and published several other minor projects. The first to pass through the printing press was Henri Estienne’s anthology of Greek works related to the life of Homer—Scaliger, you may recall, claimed that he had taught himself Ancient Greek by working his way through Homer in just twenty-one days. Scaliger’s contribution to this volume, however, was quite slight—less than three pages of critical notes. The finished book bore the imposing title:

Ὅμήρου και Ἡσιόδου Ἀγόν [Homērou kai Hēsiodou Agōn].

Homeri et Hesiodi Certamen.

Nunc primùm luce donatum.

Matronis et Aliorum Parodiæ,

Ex Homeri versibus parva immutatione lepidè detortis consutae.

Homericorum Heroum epitaphia.

Cum duplici interpretatione Latina.

The Contest of Homer and Hesiod

The Contest of Homer and Hesiod

Brought to light for the First Time

The Parodies of Matron and Others,

Stitched together from the verses of Homer with little change, but cleverly twisted.

Epitaphs for the Homeric Heroes.

With Parallel Latin Translations

The contents of this volume are as follows:

- 1-17 The Contest of Homer and Hesiod

- 18-39 Herodotus’s Life of Homer

- 40-48 Plutarch’s Life of Homer

- 49-70 Homeric Epigrams

- 71-110 Preface to the Parodies

- 111-117 The Parodies of Matron of Pitane

- 119-120 The Parodies of Hegamon of Thasos

- 121 The Parodies of Hipponax

- 122-124 Parodies of Uncertain Authorship

- 126-128 The Parodies of Timon of Phlius

- 129-134 Examples of Latin Parodies from Aelius Donatus’s Life of Virgil

- 135-176 Epitaphs for the Homeric Heroes

- 177 Scaliger’s Critical Notes on Herodotus’s Life of Homer

- 178-179 Scaliger’s Critical Notes on Matron’s Parodies

- 180-181 Henri Estienne’s Commentary

Fragments of the Philosophers

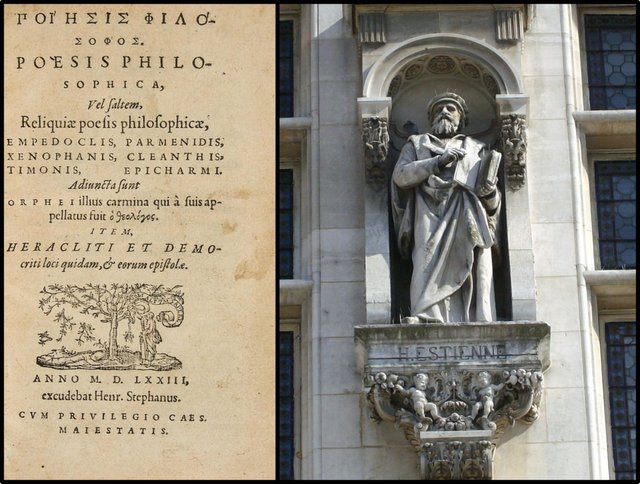

In the same year, Henri Estienne also brought out an edition of poetic fragments of early Greek philosophers under the title Poesis Philosophica, vel Saltem, Reliquiae Philosophicae [Philosophical Poetry, or at least, Philosophical Fragments]. Among the philosophers represented were Empedocles, Parmenides, Xenophanes, Cleanthes, Timon of Phlius, Epicharmus of Kos, Critias, Heraclitus, Democritus and Pythagoras. Also included are some fragments traditionally attributed to mythical or legendary figures, such as Orpheus, Musaeus of Athens, and Linus of Thrace. Scaliger, again, provided some critical notes, amounting in all to about five pages of material.

The contents of this volume are as follows:

- 3-10 Dedicatory Epistle to Reichard Streun von Schwarzenau

- 11 Cicero on Empedocles

- 12 Aristotle on Empedocles’ Account of Breathing

- 13 Scaliger on Empedocles’ Account of Breathing

- 14 Contents of the Book

- 17-31 Fragments of Empedocles

- 35-39 Fragments of Xenophanes

- 41-46 Fragments of Parmenides

- 49-52 Fragments of Cleanthes

- 54-58 Fragments of Epicharmus

- 60-74 Fragments of Timon

- 75-76 Fragments of Critias

- 78-107 Fragments of Orpheus

- 109-110 Fragments of Musaeus

- 112-113 Fragments of Linus

- 114-123 Fragments of Pythagoras

- 124-127 The Iambs of Cleanthes

- 129-155 Fragments and Letters of Heraclitus

- 156-202 Fragments and Letters of Democritus

- 203-215 Extracts from Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Eminent Philosophers

- 216-219 Scaliger’s Critical Notes

- 220-222 Henri Estienne’s Commentary

Marcus Terentius Varro

Scaliger’s first ever published work was an edition of De Lingua Latina by the Roman polymath Marcus Terentius Varro, to which he added a series of suggested emendations, the Coniectanea, or Conjectures (Paris 1565). In 1573 he and Henri Estienne brought out an edition of the extant works of Varro, which included a reprint of De Lingua Latina and an edition of Varro’s other surviving work De Re Rustica (On Agriculture):

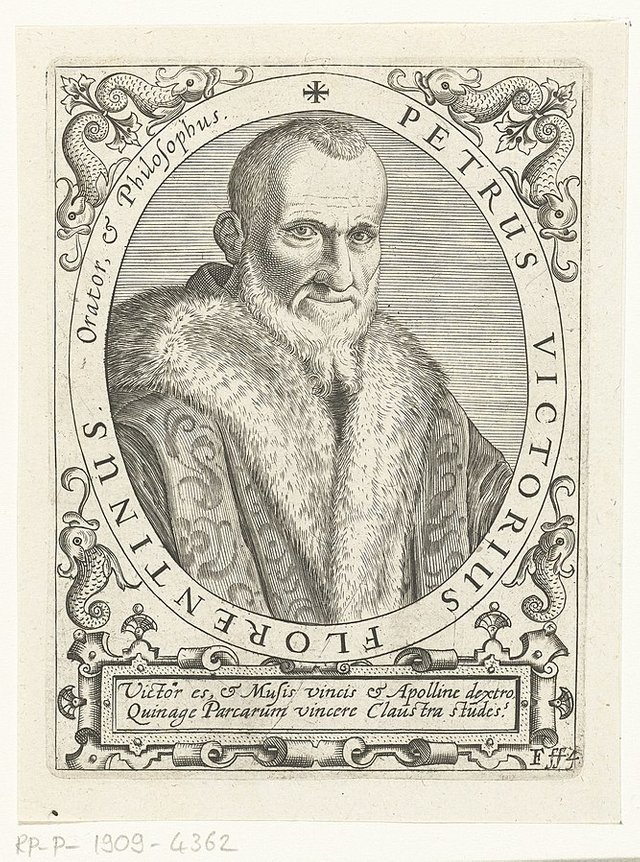

Scaliger’s other Latin undertakings, however, increasingly reveal the impact of Cujas. First, he published an edition of the works of Varro with Estienne. This was a reprint of Agustin’s De lingua latina and Vettori’s De re rustica as far as the texts were concerned. His Coniectanea on the De lingua latina he simply reprinted, adding an appendix in which he explained several passages in enormous detail, paying far more attention to details of Roman topography and history than he had in the original work. It is his notes on the De re rustica that are especially revealing. Vettori had based his edition on one particularly valuable manuscript, the readings of which he had recorded in detail in his Castigationum explicationes. Scaliger reprinted Vettori’s notes in full; and in his own notes he repeatedly accepted Vettori’s views or based his own emendations on Vettori’s collations. ‛For this correction’, he wrote at one point, ‛as for innumerable others [drawn] from that excellent manuscript, we are indebted to that excellent scholar Vettori.’ In the earlier Coniectanea he had often discussed manuscripts and the habits of scribes, but always in general terms. He had never confronted, reading by reading, a major edition from Vettori’s school. In now doing so he clearly showed that he had learned from Cujas to use the detailed findings of the Italians as the basis for a bold and sophisticated conjectural criticism. Geneva gave him the time to digest and apply the lesson. (Grafton 127-128)

Like the 1565 edition of De Lingua Latina, this edition included Adrien Turnèbe’s commentary on and emendations & excerpts from his Adversaria, and Petrus Victorius’s (ie Vettori’s) Commentary on De Re Rustica. These were discussed in an earlier article in this series, Coniectanea: Scaliger’s Conjectures on Varro.

The Varronis Opera was ready for publication in August 1573. The contents of this edition are as follows:

| Contents | Page |

|---|---|

| Encomia on Varro | 1-2 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 5 | 1-45 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 6 | 45-69 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 7 | 70-91 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 8 | 92-111 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 9 | 112-140 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 10 | 141-160 |

| 11 Indices | 76 Unnumbered Pages |

| De Re Rustica, Book 1 | 3-64 |

| De Re Rustica, Book 2 | 65-109 |

| _De Re Rustica, Book 3 | 109-151 |

| Index | 18 Unnumbered Pages |

| Scaliger’s Coniectanea | 1-176 |

| Etymologies | 177-190 |

| Scaliger’s Appendix to the Coniectanea | 191-208 |

| Scaliger’s Notes to De Re Rustica | 209-276 |

| Indices | 23 Unnumbered Pages |

| Adrien Turnèbe’s Commentary on and Emendations to De Lingua Latina | 5-123 |

| Excerpts from Turnèbe’s Adversaria | 124-165 |

| Antonius Augustinus’s Emendations to De Lingua Latina | 166- |

| Index | 12 Unnumbered Pages |

| Petrus Victorius’s Commentary on De Re Rustica | 1-98 |

Books 5-10 of De Lingua Latina were misidentified as Books 4-9, as in the 1565 edition.

Greek Epigrams

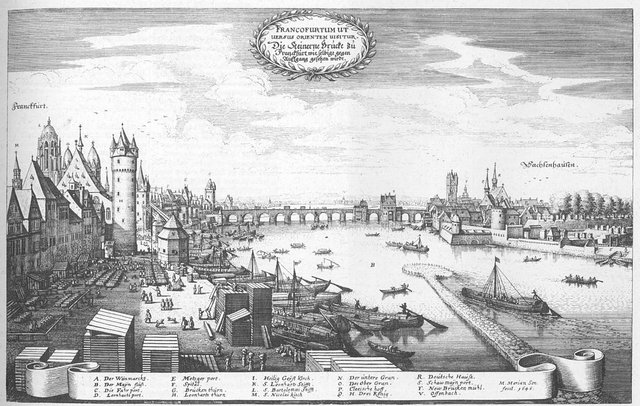

In 1574, Henri Estienne published a panegyric on the famous book-fair that had been held at Frankfurt-am-Mainz since at least the 15th century: Francofordiense Emporium. Scaliger provided parallel Latin translations for a number of Greek epigrams from the Greek Anthology and other sources, which comprised one of several appendices to Estienne’s Encomium (pages 62-75).

Four of the epigrams are of unknown or uncertain authorship. The remaining are by the following authors (the first five are from the Greek Anthology):

- Antipater of Thessalonica

- Antipater of Sidon

- Leonidas of Tarentum

- Marcus Argentarius

- Dioscorides

- Theognis

- Eratosthenes

- Hesiod

- Libanius - Description of Drunkenness

References

- Antoine César Becquerel, Souvenirs Historiques sur L’Amiral Coligny, Sa Famille, et Sa Seigneurie de Châtillon-sur-Loing, Second Edition, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1876)

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Théodore-Agrippa d’Aubigné, Histoire Universelle, Volume 2, Pour les Héritiers de Hier. Commelin [Pierre Aubert], Amsterdam (1626)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Jeltine L R Ledegang-Keegstra, Théodore de Bèze et Joseph-Juste Scaliger: Critique et Admiration Réciproques, Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire du Protestantisme Français (1903-2015), Volume 159, Pages 441-458, Librairie Droz, Geneva (2013)

- Henri II Estienne & Joseph Juste Scaliger, Homerica, Henri II Estienne, Geneva (1573)

- Henri II Estienne & Joseph Juste Scaliger, Poesis Philosophica, Henri II Estienne, Geneva (1573)

- Henri II Estienne & Joseph Juste Scaliger, Varronis Opera: De Lingua Latina, De Re Rustica, Henri II Estienne, Geneva (1573)

- Henri II Estienne & Joseph Juste Scaliger), Francofordiense Emporium, Henri II Estienne, Geneva (1574)

- Charles Seitz, Joseph Juste Scaliger et Genève, Georg et Compagnie, Geneva (1895)

- James Westfall Thompson, The Frankfort Book Fair: The Francofordiense Emporium of Henri Estienne, Edited with Historical Introduction, Original Latin Text with English Translation on Opposite Pages and Notes, Caxton Club, Chicago (1911)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Nicolas Eustache Maurin (painter), François-Séraphin Delpech (engraver), Bibliothèque de Genève, Public Domain

- Gaspard II de Coligny’s Grave (Château de Châtillon-Coligny): Château de Châtillon-Coligny, Loiret, Postcard, Crapeau (publisher), Public Domain

- South Wing of the Collège Calvin: Mourad ben Abdallah (photographer), Public Domain

- Henri II Estienne: Jean Jules Allasseur (sculptor), Hôtel de Ville, Paris, © Harmonia Amanda (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Homer: Roman Copy of a Lost Hellenistic Bust of Homer (2nd Century BCE, Baiae, Italy), British Museum, London, Public Domain

- Poesis Philosophica (Title Page): Henri Estienne, Poesis Philosophica, Geneva (1573), Public Domain

- Statue of Henri Estienne: Jean Jules Allasseur (sculptor), Hôtel de Ville, Paris, © Harmonia Amanda (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Marcus Terentius Varro: Dino Morsani (sculptor), Rieti, © Alessandro Antonelli (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Piero Vettori: Cornelis Galle (engraver), Jean Jacques Boissard (artist), Icones virorum illustrium doctrina & eruditione praestantium ad vivum effictae, Volume 1, Page 72, Theodor de Bry, Frankfurt am Main (1598), Public Domain

- Frankfurt am Main (1646): Martin Zeiller (author), Matthäus Merian (illustrator), Topographia Hassiae et Regionum Vicinarum, Between Pages 54 and 55, Merian Erben, Frankfurt am Main (1655)

Online Resources

- The Warburg Institute

- Leiden University Libraries

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Autobiographical Extracts