Philosophical-psychological consideration of the language of schizophrenia (Part 2)

The language of schizophrenia from different perspectives

Cognitivistic paradigm sees language modifications as a reflection of disorder in the underlying cognitive processes. Language is thus not an autonomous entity, but a function of intellectual domains, above all, memory, executive functions and theory of mind, as underlined by Cardella. Philosophy and phenomenological psychiatry, as well as psychoanalytic approach, are also treating language as a surface of something much more complex and often hidden. However, the understanding of the nature of these under-the-surface mechanisms differs across these paradigms, which gives us the possibility to look at the language of schizophrenia from various angles, and with different conceptual tools. The cognitive approach continues the tradition of classical Kraepelinian psychiatry, in pinpointing the linguistic defects of schizophrenia to certain processes of the intellect, only suggesting specific cognitive structures responsible for those processes. However, a problem with such a project is the lack of empirical one-to-one correspondence between any proposed cognitive structure on the one hand, and the disorder in language, on the other. Moreover, there are moderating variables, such as the chronicity of the disorder, or IQ, that can influence the direction of this relationship. For example, semantic memory, which stores our general knowledge, is often assessed in the situation of priming, which refers to the facilitated recognition of a stimulus, after the previous, semantically related stimulus. It has been suggested that hyper-priming could be the cause of the idiosyncratic language of schizophrenia, as words in this disorder share even distant associations.

The results of empirical studies, however, were not decisive – some findings pointed to the hyper-priming, some to hypo-priming, or no difference at all between schizophrenics and non-schizophrenics. However, recent experiments have urged for a different understanding of the priming capacity, namely, it is more of a state than a trait variable, depending on the course of development of the disorder. Hyper-priming is thus more often correlated with acute psychotic states, while hypo-priming could co-occur with remission phases of schizophrenia. According to the meta-analysis conducted by Doughty and Done, on the role of semantic memory in schizophrenia, no significant differences were found in priming and categorization, between people with schizophrenia, and those without it. Therefore, it seems that some confounding variables are influencing the relationship between semantic memory organization and language outputs and that they should be taken into account. Such auxiliary hypotheses that need to be postulated in this matter can urge a reconsideration of the theory, rather than its acceptance. Also, the contradictory results obtained from the priming situation undermine the normative approach espoused by this paradigm, as it clearly shows that schizophrenic patients can manifest the same level of priming as control participants. Studies investigating the link between hypothesized working memory problems and speech disorganization were equally inconclusive. It is not clear whether such problems appear as a result of schizophrenia, or are due to general intellectual deficit. Also, the connection between linguistic disorder and schizophrenia has not been shown. One of the rare findings that were consistent across various studies was the fact that schizophrenic patients made more perseverations on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), which measures the time needed to acquire the implicit changing rule of sorting cards. However, the question of moderating variables, such as duration of illness and hospitalization, can be brought up. Furthermore, underperformance on WCST is not linked to schizophrenia exclusively, but also to other disorders, like depression and autism. Needless to say, there can be methodological irregularities that influence any obtained result, or a person herself could behave differently, because of the knowledge that she is being observed and tested. The so far mentioned attempts to explicate the language of schizophrenia, reach contradictory findings and need auxiliary hypotheses in order to fully explain the language. Let us see whether theory of mind, another suggested factor in schizophrenic language development, avoids such criticism.

Theory of mind refers to the ability to interpret and predict other people’s mental states, and as such, it is a crucial social-cognitive skill, enabling us to understand the behavior of others as a consequence of their mental states. Several studies have reported the damaged theory of mind (ToM) among people with autism, which renders them typically uninterested in other people’s emotional states, their emotional expressions, or their speech, and leaves them generally apathetic towards the world. ToM is relevant in the pragmatics, a level of language at which people with schizophrenia often have problems. Thus, it could be hypothesized that because of an impaired ToM, schizophrenics do not have the knowledge of the other minds, and this lack of awareness of the others is reflected in pragmatic disturbances of their language. There are two currents of research approaching the relationship between ToM and schizophrenia – according to Frith and likeminded authors, impaired ToM is the cause of difficulty in interpreting other’s people minds. However, unlike people with autism who never quite develop ToM, people with schizophrenia start developing ToM normally, until the beginning of the disorder, which is why the other people’s minds “exist for the schizophrenic but appear quite enigmatic”. The other current of research advances the view that schizophrenia is linked with hyper-TOM, which is why people with this disorder ascribe meaning to almost everything around them, interpreting coincidental occurrences as necessary, and irrelevant events as intended for them. According to Vulević, schizophrenic patients have a peculiar relationship with indexes, signs that have no function of representation, thus, for example, the rustling of leaves is by a schizophrenic understood as a code, which he or she ought to decipher. An excerpt given by Wrobel illustrates this phenomenon:

’’Doctor: From where did you conclude that mass murder is about to occur?

Patient: I heard all round me fragmentary remarks, then this street-car ticket which dropped out of the book of some complete stranger, you can’t understand this, every word, every name has some meaning here.“ (italics is mine)

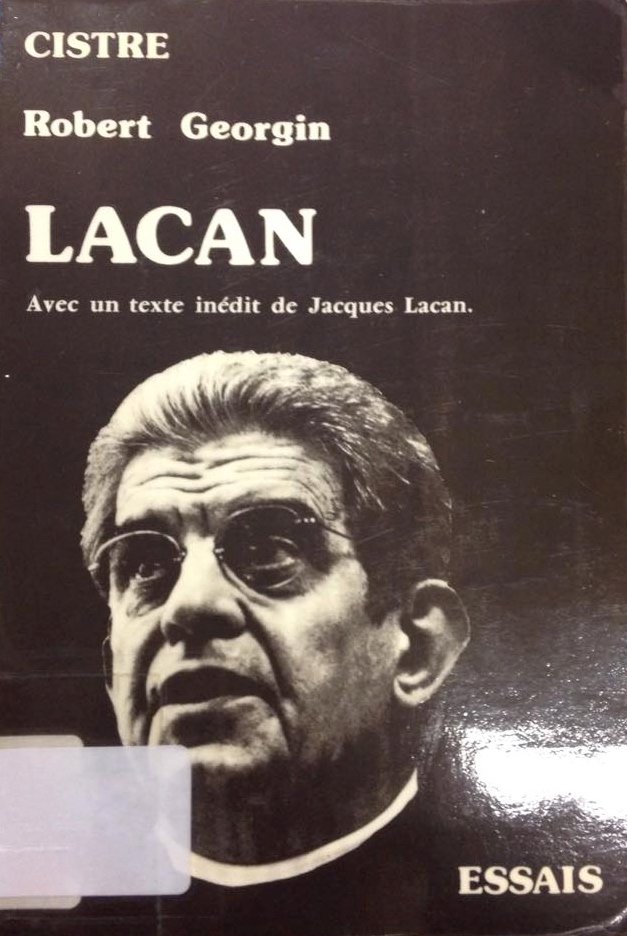

Or, as Philips described the struggle of a schizophrenic person with the overload of meanings: ’’Caught in these distorted and exaggerated poles of the sign triad as the object and the interpretant, and never the signifying agent, he loses the freedom that goes with that position.” This portrayal of the paranoid experience of a schizophrenic person resembles Lacan’s concept of the gaze of the Other, which refers to the disturbing feeling of being looked at, by an anonymous Other. A subject is becoming self-aware and uncomfortable under the surveillance, as “The gaze in itself not only terminates the movement, it freezes it…/…/ The evil eye is the fascinum, it is that which has the effect of arresting movement and, literally, of killing life.”

It seems that the theory of mind is a much more fertile construct for further theorization. A concept similar to it is mentalization, which Fonagy defines as “a form of imaginative mental activity that enables us to perceive and interpret human behavior in terms of intentional mental states (e.g., needs, desires, feelings, beliefs, goals, purposes and reasons).” The notion of mentalization, used in psychoanalytic discourse, is relevant for this topic, because the capability to mentalize is necessary for developing symbolic capacity, which is being destroyed in people with schizophrenia. Bion proposes alpha function, as an ability to attribute meaning out of “beta elements”, raw sensory data. Thus, the transformation from beta into alpha elements represents the introduction of a subject in the symbolic order, a world of conventionalized meanings. However, Jevremović adds another function to the model, called beta function, which stands for the ability of mentalization. According to him, it is necessary to digest the initial anxiety, raw, unmentalized newborn’s agitation, which he calls gama states. Beta function acts on these gama states and converts them into beta elements, which can later be symbolically represented, i.e. translated into alpha elements. Now, the ability to mentalize is a necessary precursor to the mechanism of splitting, which can be defined as a rudimentary form of cognition, of binary classification of experience into good and evil. Further on in ontogenesis, on condition that splitting has been established, projective identification occurs.

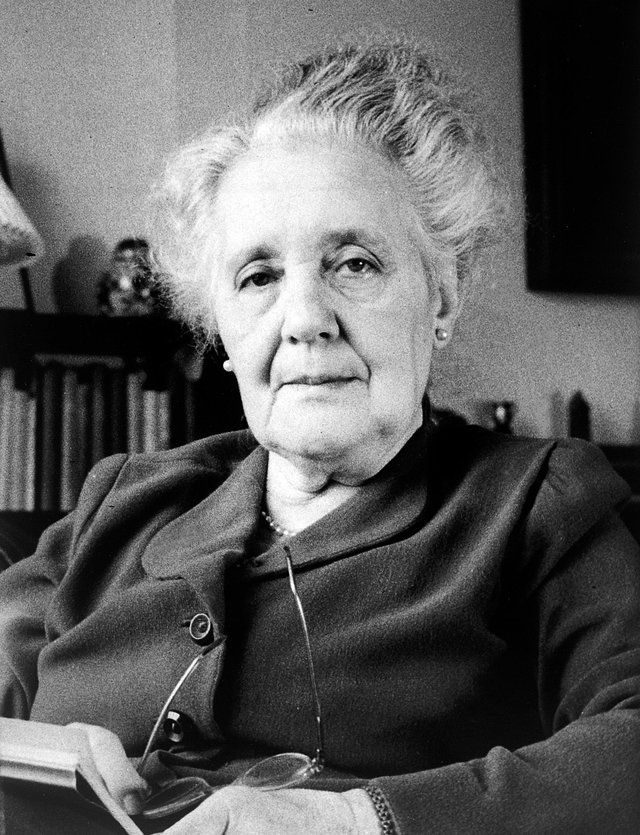

According to Schafer, projective identification happens when “the person projecting feels ‘at one with’ the object of the projection. Ogden provides an extensive conception: “Projective identification (is used to) refer to a group of fantasies and accompanying object relations having to do with the ridding of the self of unwanted aspects of the self; the depositing of those unwanted 'parts' into another person; and finally, with the 'recovery' of a modified version of what was extruded.” The notions of splitting and projective identification, both introduced to the psychoanalytic discourse by Melanie Klein, are relevant to the topic of schizophrenic language because their excessive use, as will be shown later, is often connected with psychotic disorders. For example, Klein maintained that the projection of an infant’s early sadistic attacks on the mother leads to introjection of persecutory fears, and the overuse of such processes can result in psychosis. Also, the overuse of the mechanism of splitting can disturb the cohesion of the self. Rosenfeld also asserts that excessive use of projective identification is linked with psychotic states, or, as Aguayo puts it: “unlike normals and neurotics, these psychotic patients remained identified with an internally persecuting super‐ego object – in effect, a constant attack on their own selves, while projecting good or idealized qualities onto external objects.”

Bion gives examples of schizophrenics’ use of splitting, by giving contradictory statements, directed at the analyst: “I think the sessions are not for a long while but stop me ever going out”. He mentions another patient who felt that splitting destroyed his ability to think, “The patient believes he has lost his capacity for verbal thought because he has left it behind inside his former state of mind, or inside the analyst, or inside psycho-analysis. He also believes that his capacity for verbal thought has been removed from him by the analyst who is now a frightening person.” Another contradictory statement goes as follows: “Tears come from my ears now”. According to Bion, such disorganized speech utterances have the function to confuse the analyst, to prevent a person with schizophrenia from developing verbal thought, and reaching integration. Schizophrenics resort to splitting as a way of escaping from the depressive position (a phase of integration), as well as from the possibility to name their inner world. The notion of the splitting is central in philosopher Dieter Henrich’s account of schizophrenic language. He argues that the word I has two meanings: firstly, by I, the speaker describes herself as different among other people, and, secondly, by I, the speaker sets herself apart from all other entities. Thus, I can mean either being a person, or being a subject, which is a split that people with schizophrenia cannot seem to overcome, and that can be seen in some of their statements: “I am purely subject”, or “I am defenselessly object”.

Melanie Klein (in the photograph)

According to Jakobson’s and Lübbe-Grothues’s analysis of Hölderlin’s poetry, his late poems show absence of deictic words or shifters, words that have no meaning outside the context to which they refer, for example, “I”, “my”, “your”, “here”, “now”, etc. Compared to his earlier poems, which contained a lot of exclamations, addresses, questions, generally, dialogue-oriented statements, his later poems show a break-down of the deictic frame. This is characteristic of the language of schizophrenia, the distinction between I and You, for example, can be destroyed, and the form of a dialogue disappears. Furthermore, in his late poetry, there is no reference to the past or the future, there is only “despotism of the present”. Reflecting on Hölderlin’s poetry, Heidegger concludes: The foundation of human existence is conversation as the authentic occurrence of language. /…/ Language, however, is ‘the most dangerous of goods.’ According to Heidegger, “language is the house of Being”, one exists in the symbolic discourse, and, more precisely, in a dialogue (“We – people – are a dialogue”). People with schizophrenia often do not express themselves in a dialogic form, or they fail to be understood by a listener, or try to unconsciously confuse the listener, for reasons that are still beyond our understanding. Maybe a dialogue is no longer possible, because the distance between the schizophrenic subject and the Other cannot be overcome. As Kepinski put it: “In schizophrenia, the barrier between me and the surrounding world is broken. As an apparent result of an excessive intensity of antagonism between them, the dike breaks and the turbulent contents of the internal world surface into the external world, and the external world, in turn, plunges into the interior.“

Conclusion

In this essay, I have attempted to approach the language of schizophrenia from different paradigms, including cognitivism, psychoanalysis, philosophy, phenomenological psychiatry, and linguistics. Although we cannot provide any conclusive explanation of the specific nature of the schizophrenic discourse, it is nevertheless important to continue analyzing it, for it can give us further insight into schizophrenia itself, as well as the language development. The topic of language peculiarity in schizophrenia can lead to inexhaustible research and theorization, and it also allows for an interdisciplinary approach. Thus, a possible theme of further analysis could be the assessment of such interdisciplinary interpretation. Finally, I would like to quote a verse by Hölderlin, which captures the intimate relationship between language and ontology: "That is why language, the most dangerous of goods, has been given to man ... so that he may bear witness to what he is....”

References

Aguayo, J. (2009). On understanding projective identification in the treatment of psychotic states of mind: The publishing cohort of H. Rosenfeld, H. Segal and W. Bion (1946–1957). The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 90(1), 69-92.

Bion, WR. (1954). Notes on the theory of schizophrenia. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 35, 113-118.

Cardella, V. (2018). Language and schizophrenia. Perspectives from psychology and philosophy.Routledge.

Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2012).What is mentalization? The concept and its foundations in developmental research. In:

Midgley N and Vrouva I (eds.) Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and

their families. (11 - 34). Routledge.

Heidegger, M. (1978). Letter on humanism in D. F. Krell (ed.), Basic Writings. Routledge.

Heidegger, M. (2000). Elucidations of Hölderlin's poetry (Contemporary Studies in Philosophy and the Human Sciences).Humanity Books.

Jakobson, R., & Lübbe -Grothues, G. (1980). Ein Blick auf Die Aussicht von Hölderlin . In Hölderlin , Klee, Brecht: Zur Wortkunst dreier Gedichte (Suhrkamp). Poetics Today, 2(1a), 27-96.

Jevremović, P. (2012). Telo, fantazam, simbol. Službeni glasnik.

Ma, Y. (2015). Lacan on gaze. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 10(1),125-137.

Muller, J., & Brent, J.(2000). Peirce, Semiotics, and Psychoanalysis.Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ogden, T. (1979). On projective identification. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 60, 357-373.

Spitzer, M., Uehlein, F., Schwartz, M.,& Mundt, C. (1992). Phenomenology, language & schizophrenia. Springer-Verlag.

Vulević, G. (2016). Razvojna psihopatologija. Akademska knjiga.

Whistler, D. (2009). Hölderlin’s atheisms. Literature and Theology, 23(4),401-420.

Wrobel, J. (1990). Language and Schizophrenia.John Benjamins Publishing Company.