The Question Property Investors Should Be Asking – Australian Property Market Update – May 2018

Every month or so I write a market update for the PropertyInvesting.com community. Here’s an updated version highlighting my thoughts on the latest auction clearance rates, recent changes in home prices, plus the question property investors should be asking.

The Latest Auction Activity

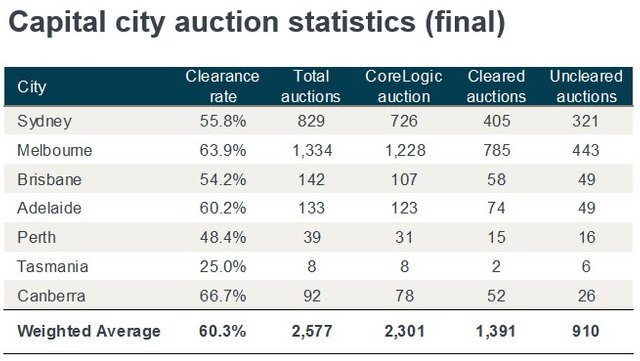

Demand in the auction market is looking bleaker by the week. Last week, the clearance rate barely hit 60 percent. The weak numbers are due to a spike in supply, with sellers bringing a total of 2,577 homes to auction. The previous week’s total was 1,799.

Demand in Sydney dropped to its lowest point for the calendar year, with about 56 percent of sellers finding a buyer. Melbourne’s auction market remains stronger than Sydney’s, with 64 percent of auctions clearing.

Here are all the latest capital city results according to CoreLogic:

source

Recent Changes in House Prices

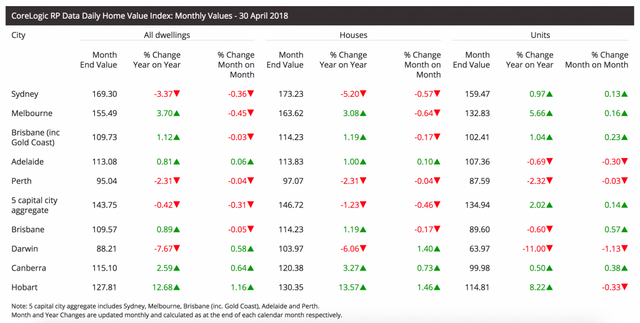

The pace at which home prices are falling in our largest cities seems to be accelerating. Looking back over the month of April, dwelling values fell 0.36 percent in Sydney and 0.45 percent in Melbourne. Home prices in Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth remained for the most part unchanged.

Below, you can see all of CoreLogic’s data for the past month. Units, which are obviously less expensive than houses, continue to attract more buyers. While the Sydney house market has fallen 5 percent over the past year, unit values are up 1 percent. In Melbourne, units have grown twice as much as houses over the past year, 6 percent and 3 percent respectively. In reality, it’s probably more accurate to say that units are not falling in value as fast as houses over the last few months.

source

Will Home Prices Keep Falling?

source

That depends on whether the banks can keep churning out the loans.

A few weeks ago, I posted an article on PropertyInvesting.com surveying several analyst opinions on the future of home prices, their views ranging from “It’s All Good” to “Oh @%&#, We’re Screwed!”

As the saying goes, there are as many opinions as there are a$$holes, but one thing any analyst with a brain can agree on is the premise that home prices are primarily at the mercy of interest rates.

While population growth and tax incentives have helped to fuel demand for housing, one fact is undebatable (at least from my perspective): people are able to afford today’s house prices because interest rates are at record lows and banks have had access to plenty of freshly minted money (not to mention free reign to lend to whomever they please).

As a side note, I made a case for this money supply view three years ago when many investors thought it was ridiculous. You can see for yourself in the comments on my article “The Ultimate Reason Real Estate is So Expensive”. There's also an updated version on Steemit :)

Back to my point… If cheap and readily available credit really is to blame for the imbalances between home prices and our incomes, then higher borrowing costs or tightening lending criteria would most certainly equate to lower house prices.

On the other hand, if borrowing costs were to keep falling, or if serviceability criteria loosened and more people qualified for loans, expensive properties would be in reach to more buyers. That would pull even more demand from the future and cause home prices to start rising again.

So where is the lending market headed? That’s the question property investors should be asking.

In Regulators We Trust

Most people believe that the future of interest rates rests solely in the hands of our regulators. After all, the RBA decides to cut the cash rate and the banks either do the same or they look like greedy bastards.

As investors, we place our trust in the RBA and APRA to never purposefully do anything that would destroy the housing market and subsequently the economy. If higher borrowing costs would break homeowners, then RBA just won’t raise rates.

Well, the reality doesn’t play out that way. There’s a limit to the RBA’s power that most people aren’t aware of. Our regulators have the ability to determine short-term rates, but they can’t control longer-term rates. That has more to do with the bond markets. (For more on how the RBA influences interest rates, check out this article I wrote.

The US Dollar and the Federal Reserve

Supply and demand (and subsequently price) in the bond market reflects the trust (or lack thereof) that investors have in governments and corporations. As long as people are confident that these entities will eventually repay their debts, their bonds are perceived as low risk, and investors are willing to accept a low yield.

Since 2008 (and long before), bond yields have been super-low because the Federal Reserve (and virtually every other central bank) has been driving down interest rates by buying bonds. This “monetary easing” causes bond prices to rise, which conversely lowers bond yields.

If the Fed were to stop buying up bonds, then supply would increase, bond prices would fall, and bond yields would rise. Higher bond yields equate to higher interest rates in the broader economy.

Bankers: “Show Me the Money!”

Interest rates would rise because Australian banks would have to start paying more for the money they borrow (through the bonds they sell). Because Aussies aren’t too keen to keep a lot of money sitting around in bank accounts earning 1.5 or 2 percent per annum, our banks must look elsewhere for money to lend out.

They find the money they need in the overseas lending market. They borrow (essentially selling a bond) at a low yield, and then charge a little bit more to borrowers here so they can make their profit. If the banks’ borrowing costs were to rise, then the interest rate on your variable mortgage would likewise go up.

Here in Australia, there is no 30-year fixed rate mortgage. When you invest in property here, you carry interest rate risk for as long as you owe the debt.

A Royal Pain in the Commission

Banks make profits primarily by lending out money to homebuyers and investors, as well as businesses. As long as debt is increasing in our nation, the banks can make money and their share prices have a chance of going up.

Banks have an incentive to keep lending criteria as generous as possible (short of taking on too much risk – although greed can make tough to say when enough is enough). That’s where our regulators are supposed to step in and hold the banks accountable – to prevent them from getting too greedy and short-sighted. Of course, who can blame them. They’re just working within the loose lending environment created by ultra-low interest rates.

Here in Australia we’ve been hearing a lot about the Royal Commission into misconduct in the banking industry. It has recently uncovered some evidence that banks have been pushing the lending criteria boundary a little too far. Many lenders have been underestimating household expenditures and qualifying borrowers that will likely not have the extra funds in their budgets to stay afloat if and when interest rates rise.

I’ve spoken to a few brokers who have said that after this expose, banks are now requiring much more evidence to validate actual household expenses, like requiring copies of bank statements. If our regulators decide to stick it to the banks and take more drastic measures to crack down on loose lending, it could become even more difficult for investors and homebuyers to get loans for expensive houses.

A Statistical Inevitability

The RBA met this week and decided to leave the target cash rate on hold at a record low 1.50 percent. It’s been nearly two years since the RBA cut interest rates, and seven and a half years since we’ve seen an interest rate rise.

Currency traders are now pricing in a one-in-three chance of a rate hike by the end of 2018. A move upward within the next 12 months is essentially a coin toss and it’s not until late 2019 when a rate hike is fully priced in.

But some analysts more pessimistic on the Aussie economy suggest the RBA will be forced to slash interest rates yet again.

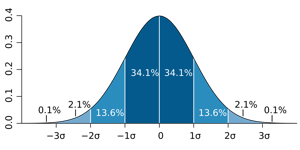

One thing that we know for sure is that someday, possibly before those buying homes today have paid off their mortgages, interest rates will rise dramatically. It’s a statistical certainty called mean reversion – prices and returns eventually move back toward their mean or average.

The long-term average variable mortgage rate is around 8.5 percent. That’s a little more than 300 basis points above where we are today.

According to my calculations, it would only take a rate rise of about 150 to 200 basis points to return many borrowers back to the pain people felt in 1989 when mortgage interest rates were around 17 percent. I was just starting high then, but from what I hear, it wasn’t a fun time.

So, what does the future of the Aussie lending market look like from your perspective?

Will borrowing costs rise or fall in the short-term?

Will loans become easier or harder to get?

How long until the variable mortgage interest rate reverts to the average of 8.5%?

Jason Staggers

Thanks for the info. I wish it keep falling or at least stable.

Thanks for reading. I think you'll get your wish.

Thanks for these vital information. Thanks for educating me this morning (It's 7:07am in Nigeria). Thanks for visiting my blog, thanks for the upvote @jasonstaggers

Upvote and resteem. Thank you Jason, a very worthwhile report and readers such as myself highly appreciate it.

Thanks Lucky :)

"Every month or so I write a market update for the PropertyInvesting.com community."

Hey friend, you are overdue ;)

Hope you can give us an update soon.

UPVOTE THIS

Congratulations @jasonstaggers! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

To support your work, I also upvoted your post!

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPProperty tax and regulations...much?

Yes, indeed. Plenty of incentive to keep home prices propped up.

Interesting data, thank you!

I would like to see house prices ease or at least be stable.