Porn, pop culture and the teen abuse crisis

Worrying numbers of teenage girls are enduring violent relationships — fuelled by the sexualised world of the internet. Angela Neustatter meets the girls who have escaped abusive “first loves”

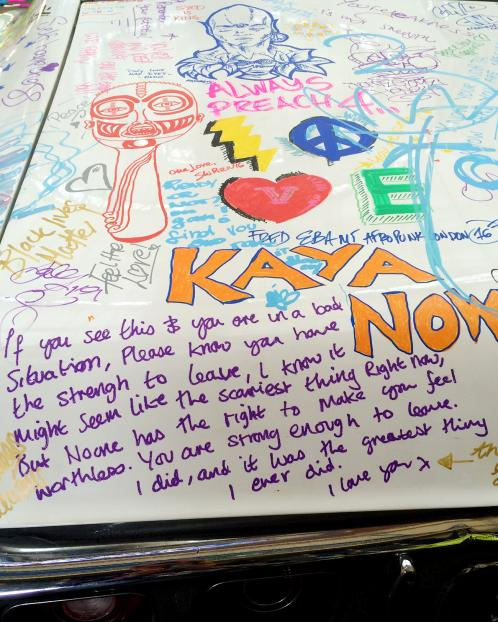

mogen Paton, finely built with a pale blonde bob and a sassy, confident smile, is an intriguing sight, perched against the wreck of the Chevrolet Impala that she takes to music festivals and events around the country. Surely the car, with its crushed grille, crumpled sides and body decorated with scribbles, drawings, comments and poems, is an entertaining display of youthful art? Well, not exactly. The Bad Karma Impala, as she calls it, is a stark metaphor for the wrecked state that Imogen was left in after becoming a teenage victim of domestic violence and extreme emotional abuse.

Imogen was a 19-year-old art student when she met and quickly moved in with her first real “love”. “I think I wanted someone badly to represent the father I lost aged 15,” she says. “He was very smiley and I liked the fact he came from a different class and culture to my middle-class upbringing.” But the violence started quickly, and it emerged that he had a crack cocaine problem. “I wanted to help him, but when I said this he put his hands around my throat and threatened to strangle me. From there, things escalated. He’d throw my belongings, and then me, down the stairs. There were always scary threats, but he could be very loving and I so badly wanted that, so I excused his behaviour. I convinced myself it was my fault for upsetting him by doing something bad.”

Imogen was with him for three years before she left. “He began to stalk me on the streets,” she says. “I remember he nearly broke my nose in broad daylight outside this pub. Then he started trying to break into the flat where I lived. I had a police alarm fitted and CCTV outside, but he still tried to set the flat alight through the letterbox. He had a photograph that he had taken with me just wearing underwear. He made a poster advertising me as a prostitute with my real name and phone number. After he tried to run me over, he was arrested and jailed. He did two months, but he didn’t bother me after that.”

Last month, the Office for National Statistics reported that 11% of girls aged between 16 and 19 in England and Wales say they have experienced domestic abuse in the past year. It is the grimmest of ways for our children to experience first love.

According to a survey by SafeLives, a charity working to help victims of domestic abuse, the problem is even more widespread. A quarter of 13- to 17-year-old girls have experienced some form of physical abuse from a partner. And although the charity found 95% of victims of intimate-partner violence were girls, 18% of boys also reported some physical abuse.

There are cultural reasons for this current level of teenage domestic abuse. Children — who might once have got to know a boyfriend or girlfriend before getting into a naive and fumbling exploration of sexuality — are increasingly finding themselves with someone they met online that they believe they have got to know, but about whom they actually know little.

Diana Barran, the retiring CEO of SafeLives, is one of many experts in this area who believes social media plays a worrying part. “Young people are so present online, tell so much about themselves and see it as the place to communicate with friends,” she says. “But people behave differently [online] because there is no accountability. It enables people to do very harmful things.”

Define the Line, a survey by the Avon Foundation for Women in partnership with the domestic-violence charity Refuge, found that almost 40% of 16- to 21-year-old girls thought that coercive and controlling behaviour in relationships had become normalised because of the abuse they see in society, the media and online pornography. One in three young people say they find it difficult to define the line between a caring action and a controlling one.

Hera Hussain, a dynamic, award-winning entrepreneur, set up Chayn, a charity that helps people threatened through social media. SafeLives uses its toolkits to train domestic-abuse workers.

“We realised early on that a lot of people didn’t know how technology can be used by partners to spy on and damage their victims,” Hussain says. “Telling them just to get off social media altogether is not realistic. They shouldn’t have to give up what can be a very valuable form of communication.” Not just valuable, but seemingly essential to the new generation.

Chayn’s website advises people how to stay safe online. Its toolkits are particularly valuable for those trying to build a domestic violence case without a lawyer.

In the private world of mobile-phone communication, it is all too easy for someone to convince a partner to send intimate and graphic messages or files. One mother I spoke to recalls the shock of what she found on her daughter’s phone.

“Amber was 15 when she got together with Joe,” she says. “He seemed like a very pleasant lad and she went out with him for some time. But he would never introduce her to friends, or meet hers. Then he started tormenting her. He told her he wasn’t sure if he wanted to be with her, and I saw how unhappy she was. She didn’t talk to me, so I decided to look at her phone. It was full of graphic sexual messages from him, and it was clear from her replies that their sex life was ‘inspired’ by porn. None of it was about caring for her. I told her what I’d seen and that I’d looked because I was worried about her, but of course she was furious. To my relief, it ended and she seems happy again going out with the friends she had lost touch with.”

Gary Wilson, host of the website Your Brain on Porn, believes the consumption of porn by teenagers and preteens (the average starting age for boys is just 11) is a far more serious risk than we may realise.

He points to 37 neurological studies that focus on how teen brains have great neuroplasticity, meaning that dramatic rewiring can take place, setting a pattern for the future. “Some teenagers today wire their arousal to internet porn’s unnaturally intense synthetic stimuli for as long as a decade before they try to connect with real partners,” he says. Wilson argues that easy access to internet porn plays a part in the increasing violence in teenage relationships. “While glued to his screen, a young man is not learning courtship skills or spending time getting to know a girl as a person. Now, a 17-year-old virgin envisions his first time with his first girlfriend will also involve two of her friends and some handcuffs.”

An analysis of the content of porn websites published in the academic journal Violence Against Women found that “of 304 scenes analysed, 88.2% contained physical aggression, while 48.7% contained verbal aggression. Perpetrators were usually males. Targets of the aggression were overwhelmingly female.”

Melinda Tankard, who co-edited Big Porn Inc: Exposing the Harms of the Global Porn Industry, suggests that “we are conducting a pornographic experiment on young people — an assault on their healthy sexual development. Girls and young women describe boys pressuring them to perform acts inspired by the porn they consume routinely. Some see sex only in terms of performance, where what counts most is the boy enjoying it. Growing up in a pornified landscape, girls learn that they are service stations for male gratification.”

There is some encouraging news, though. As it becomes clear that a generation of children is in danger of experiencing a grimly destructive kind of “first love”, a range of projects are being developed to tackle it.

The actress Olivia Colman is helping to raise funds for Tender, a charity that goes into schools to talk about relationships, how to recognise coercion and abuse and where to go for help. It also talks about pornography, sexting and their consequences. Kate Lexen, the charity’s education manager, believes it is vital to work with boys as well as girls. “Boys can be very confused and uncertain,” she says. “They may have had experiences that have made them mistrustful of women, and violence is often a male way of dealing with feeling out of control. Although we stress that abusive behaviour is never acceptable, we also prioritise empathy for everyone.”

Around the country, the Big Lottery Fund supports 63 projects under its women and girls initiative; these include focused support for girls at risk of domestic violence. The charity Solace Women’s Aid, which runs refuges for females aged 16 and upwards, has just set up Here2Change, a programme to go into schools and provide peer support and guidance. It is training both girls and boys, in some cases survivors of partner abuse.

Belinda, a likeable, chatty 22-year-old, is part of the team, and feels her “frankly horrifying” experience will be valuable in doing this work. Her relationship with Tom began when she was in her teens. She knew little about him when they got together . The first warning sign was when he flicked a lighter at her and set her hair on fire on New Year’s Eve. “I should have got out then, but he had treated me so perfectly up until then, I imagined it was a one-off,” she says. When she argued with her parents about her relationship, Tom suggested she move in with him. “Then things began. He locked me in my room, took my phone, began hitting me and screaming I made him do it. When he stamped on me and broke my ankle, I left him and moved into a homeless hostel.”

That was two years ago, and for the past year Belinda has had a new boyfriend. She can still hardly believe how gentle and considerate he is, and what good times they have together. Without the Solace training, which both have done, she is not sure she would have dared to trust him. She is lucky. For others, abuse during the intensely challenging teen years can cast long shadows on relationships in future.

Sarah was 15 when she met Stu and became another victim of teen abuse when he posted photos and recordings of her in the most intimate situations on the internet. Today, with the support of SafeLives, she is sharing her experience with a group of young women who have suffered domestic abuse.

After she got together with Stu, she says, “I found out he was using drugs and I did too, for a short time. He began to hit me, saying I made him do it with my behaviour. I was so young and I didn’t know anything about this kind of behaviour.”

As the relationship became more controlling and abusive, Sarah lost touch with all her friends. “I was very depressed and suffering from anxiety. I moved away to live at home, but I let Stu come live with us because I thought we would have a better chance of things working there. I was wrong. It was really, really bad. Stu was told to leave our house and I broke up with him then. We had been together 2½ years. He had recordings and photos of me. He put them up on Instagram and made pages about me. He followed all my family and friends so they would see. In the end he got arrested and was charged with child pornography for the pictures, as well as for doing drugs, and he went to prison.”

For Imogen, the owner of the Bad Karma Impala, her first disastrous relationship set up an emotional template. Although a relationship with a kindly man followed, she then found herself drawn to another man who began to abuse her. They were together two years, but the slaps, the shouting and the demeaning began early on. He pushed her downstairs when she was pregnant, then blamed her for doing it herself. The cataclysmic end came when Imogen returned home with the baby the day after she gave birth. That evening they had an argument and he slapped her, baby in arms. “In that moment,” she says, “I realised things would never change, that this relationship would affect my children, and that I must get out. I told him I had to leave.”

The following morning, he told her: “If you leave me, sweetie, you have to believe me, I will kill you. I can make it look like suicide and I will not lose a single night’s sleep over it.”

She managed to record his threat on her mobile phone and, when he was arrested, she went on the run.

If Victim Support had not suggested she go to Solace, she scarcely dares to think what her life would be like now. What a pleasure, then, to hear Imogen tell of the help she received in rebuilding her life, having a home where she could feel safe, and attending courses that helped her understand what happened and see she was not to blame. All this pushed her to create her own Arts Against Abuse organisation to raise awareness and funds for Solace.

During this time, the police had found the 1968 Chevrolet Impala that her partner had smashed on a crazed night. “It was all I had left from that relationship,” she explains, “so I decided to decorate the car and take it to festivals and events.” ‘

Imogen tells how people are drawn to see what it is all about. “Once I tell my story and what the car represents, men and women open up,” she says. “People then draw and write poems, hopes, dreams, pictures on the body of the Impala. Instead of just another bruised eye or trauma-based image directed at educating the public on violent abuse, I want those who already know how awful and varied abuse is that there is life afterwards.”