A millionaire's corruption case exposes China's dirty tactics in Africa...

It sounds like a Hollywood movie. A respected Hong Kong financial magnate allegedly plans a clandestine meeting with the president of Chad in the middle of the dusty Sahara Desert, and offers him a $2 million gift to secure oil rights for a Chinese conglomerate.

In another scheme, Chi Ping Patrick Ho, according to United States prosecutors, sends the now foreign minister of Uganda, who was then the president of the UN General Assembly, a $500,000 bribe for business advantages, through the New York banking system.

All this was allegedly planned under the noses of the world's top diplomats in the corridors of the United Nations in New York, where Ho ran an energy NGO.

In November 2017, Ho and Cheikh Gadio -- the Senegalese failed presidential candidate and former foreign minister, who allegedly arranged the deals -- were arrested in New York on multiple bribery and money laundering charges. This week, the trial date was set for November 5, 2018. Aged 68 years old and in ailing health, Ho risks spending his remaining years behind bars. He has pleaded not guilty.

This case, however, is about more than one man's spectacular fall from grace. It offers a rare window into Chinese corruption in Africa -- something academics, politicians and business people have long suspected existed but found difficult to prove.

What's more, with the mountain of evidence seemingly against the defendant, legal experts are wondering whether Ho might be asked to expose other corrupt parties to reduce his sentence.

China's 'competitive advantage'

Western companies in Africa have "long spoken of the competitive advantage Chinese companies have on the continent," says Andrew Spalding, a professor at the University of Richmond and expert in anti-corruption law. "And the dramatic increase in China's commercial presence tends to confirm it."

China's goods trade alone with Africa totaled $188 billion in 2015, compared with $53 billion for the US. As China has become the continent's biggest economic partner, Chinese companies have found themselves operating in countries with high corruption ratings without domestic legislation to answer to. Thirteen Sub-Saharan African nations ranked in the bottom 30 of the 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index.

"If I am an American company and I want to do a deal, particularly in Africa and less developed areas, and I am approaching African officials but losing out because Chinese companies are bribing those officials, I am going to be irked," says Rob Precht, president of New York-based legal think tank Justice Labs.

American and British companies have been living with the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the UK Bribery Act for years. Although China formally adopted a foreign bribery law to comply with the UN Convention Against Corruption in 2011, it has done "next to nothing to enforce it," says Spalding. He adds: "The hope is that if Western companies continue to pressure overseas governments to change, that competitive advantage will eventually disappear."

For centuries, bribery has not even been considered a bad thing in China

Rob Precht, president of Justice Labs

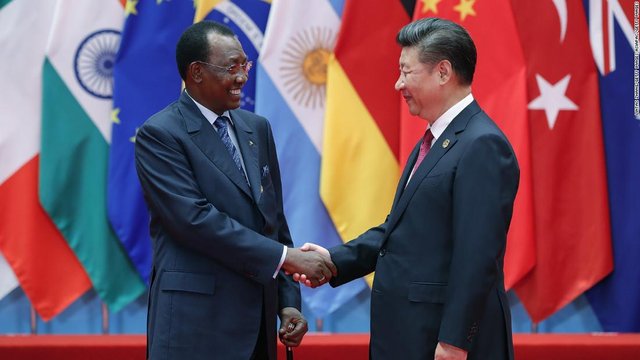

Chinese president Xi Jinping's high-profile corruption crackdown at home virtually ignores foreign bribery, according to some observers. "For centuries, bribery has not even been considered a bad thing in China," says Precht. "But as China becomes a partner in the world community, these issues are going to become more important."

Before he became President of the United States, Donald Trump had slammed the FCPA for turning America into "the policeman for the world." A foreigner in a different country who merely sends an email relating to corrupt practices through a US server can be prosecuted under the act. "Let them clean up their own act, we shouldn't be cleaning up their act for them," he told CNBC in 2012.