The Role of Media as Agitation and Integration Propaganda in Africa (DR Congo)

Please visit mentalhealthcongo.com for more comprehensive blog posts.

Introduction:

Ethnic conflicts in most Central African countries are typical civil wars comprising multiple overlapping conflicts intermingled with large-scale offensives by the government army, proxies, rebels and civilians. This paper will examine the efficacy of propaganda strategies of political leaders during the Hutu vs. Tutsi ethnic conflicts in Rwanda and Burundi from 1962 to 1994 and the Nande-Hunde vs. Banyamulenge ethnic conflict in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) from 1995 to present day. In this paper, I argue that political leaders in Central Africa utilize the media as a propaganda tool to frame a psychological mindset that alienates some ethnic groups from other ethnic groups, therefore prolonging ongoing ethnic conflicts and civil wars in order to remain in power.

In Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present, Taylor explains that the media can be a powerful tool that can frame the mindset of mass audiences and incite them to take action. He states that " propaganda forces us to think and do things in ways we might not have done had we been left to our own devices. It obscures our windows on the world by providing layers of distorting condensation. When nations fight, it thickens the fog of war." (Taylor, 1995, pg 1). In an attempt to understand the role that the media plays in Central African ethnic conflict, this paper will examine three particular themes. The first theme that will be discussed is the use of media during political elections to fuel ethnic conflict. The second theme that I will touch on is the need for politicians to reinforce the notion that belonging to an ethnic group or that being the majority ethnic group is more important than having a national identity. The third theme will draw from the first two themes and demonstrate how effortlessly the media can sharpen the focus of the populace and lead them to action or non-action.

Media as Agitation and Integration Propaganda:

To grasp, to a large extent, the effects that media as a tool for agitation and integration propaganda plays in central African conflicts, I will employ the method used by Ellul in Propaganda, the Formation of Men's Attitudes. In addition to being utilized as a tool of conflict, the media can also be used as a signifier to mediate life and death, social relations and daily security. In order to understand how the media is used in Central African ethnic conflicts as agitation and integration propaganda, it is crucial to understand what these terms mean. According to Ellul, agitation propaganda is a form of propaganda that leads men from mere resentment to action or non-action. He states that "governments also employ this propaganda of agitation when after having been installed in power, they want to pursue a revolutionary course of action." (Ellul, 1973, pg.70). Ellul further explains that in the case of agitation propaganda subversion aims at the resistance of a segment or a class and an internal enemy is chosen for attack. Integration propaganda aims at making men adjust themselves to desired patterns. He explains that "the more comfortable, cultivated and informed the milieu to which it is addressed, the better it works." (Ellul, 1973, pg 71). Integration an agitation propaganda often complement each other. Once a politician gains power through agitation, he/she often immediately begins to apply integration propaganda to maximize his/her influence.

Agitation and Integration propaganda have played a significant role in Central African political and ethnic conflicts by prolonging ethnic conflict between groups. In order to understand the relationship between propaganda and ethnic conflict, it is crucial to also understand the history of conflict between Hutu and Tutsi groups in Rwanda and Burundi and the Nande-Hunde vs. Banyamulenge conflict in eastern DRC.

Historical Background of the Hutu vs. Tutsi Conflict in Rwanda and Burundi:

Rwanda is known for its ongoing bloody legacy or civil wars between Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups which has been the case even before colonialism. The conflict was further fueled by Belgian colonizers when King Leopold II of Belgium set foot in the land in the early 1900s. The Belgian colonizer, with the notion that something of a caste structure has already begun to emerge before the colonial period, has decided to define the Rwandan situation. In Ethnic Genocide, Lemarchand explains that it was much simpler and more efficient to view Rwanda as consisting of a Tutsi aristocracy and a Hutu peasantry and to pursue a policy of indirect rule that would maintain the dominance of one over the other. Film was one of the media outlets used to reinforce this separation. Below is a rare documentary from 1939 showing how Tutsi kings enjoyed their nobility and ruled over Hutu peasants. This was a way to establish and maintain that Tutsis were superior to Hutus.

[embed]

Here is another video giving a brief history of the Hutu vs. Tutsi conflict before the colonizers arrived and how the conflict escalated after the colonizers left.

[embed]

Rwanda gained its independence from Belgium in July 1962. Three years before independence, as shown in the above videos, the majority ethnic group in terms of numbers were the Hutus. They succeeded to remove Tutsi king Kigeri V. and killed tens of thousand of Tutsis while simultaneously forcing them into exile to neighboring countries such as Burundi and Uganda. With years of ongoing conflict following their independence from Belgium, in the spring of 1994 the Hutu ethnic group committed one of the greatest human rights violations by killing and raping approximately 800,000 people in the country including Tutsis. The main goal was to exterminate Tutsi groups. The crime has been recognized internationally as the Rwandan genocide by the United Nations' Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in Tanzania (ICTR) has been created in order to punish those responsible for the crime.

Members of the Tutsi ethnic group who went into exile before Tutsi king Kigeri V. was removed from power started their own rebellion in neighboring countries. In Burundi, following a deadly conflict in 1972, members of the Hutu ethnic group were mass murdered by the Tutsi army. Subsequently, in 1993 with the help of the remaining Hutus in Rwanda, the Hutu ethnic group killed approximately thirteen percent (13%) of the Tutsi population in Burundi. Although the conflict and massacres in Burundi did not get as much media attention as the one in Rwanda did, the international Community has also recognized it as genocide.

Historical Background of the Nande-Hunde vs. Banyamulenge Conflict in Eastern DRC:

The ethnic conflicts in Rwanda and Burundi created a great influx of refugees into the DRC from both Hutu and Tutsi groups in 1995. The influx of refugees immediately caused a serious security problem because the area where they were residing, North and South Kivu, was occupied by Congolese people of Nande and Hunde origin or ethnic groups. As soon as the refugees were settled, the ex-FAR (Rwandan Armed Forces) soldiers aimed to set up a “Hutu Land” of both Rwandan and Burundian Hutus to exterminate both Tutsi and local Nande and Hunde Congolese people. (Prunier, 2008, Pg. 37). The Nande and Hunde people, who already opposed the migration of Rwandans and Burundians into the DRC decided to retaliate and force both Hutu and Tutsi groups, who they labeled as “Banyamulenge” or “Banyarwanda” to leave. This lead to a conflict that killed more than 3.3 million people and destabilized most of central Africa, making it the deadliest conflict since World War II. (Prunier, 2008, Pg. 37)

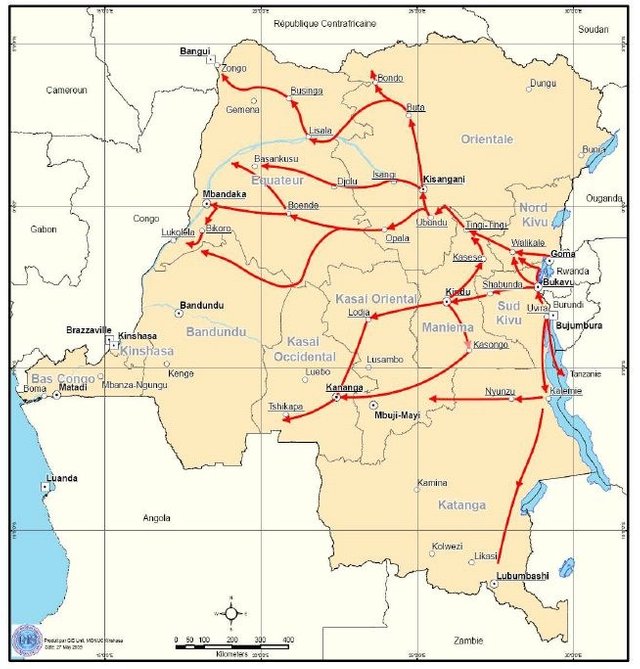

Below is a map that shows the dispersal of Hutu refugees in 1994 ad 1995 from Rwanda and Burundi to the DRC:

The Ways that media and Agitation Propaganda fueled ethnic conflict in Rwanda, Burundi, and the DRC:

Four years after independence from Belgium in 1962, Michel Micombero, the first president of Burundi of Tutsi origin initiated a process of political mobilization that gradually reached every sector of Burundi society, activating one group after another, pitting princes against princes, monarchs against Republicans, army men against civilians, north against south, Hutu against Tutsi. (Lemarchand, 1975, pg. 5). He used the radio in several instances to insult members of the Hutu ethnic group. Below is a tweet in French from a Tutsi citizen of Burundi confirming that Micombero insulted people on the radio.

In 1993, Burundi held its first democratic elections, which were won by the Hutu-dominated Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU). FRODEBU leader Melchior Ndadaye became Burundi's first Hutu president. Instead of seeking peace during his tenure, Ndadaye also sought to retaliate and make the Hutu ethnic group the dominant group in the country. He immediately started propagating that another Tutsi presidency will lead to a Hutu genocide on the radio and television and formed a group of rebels to fight Tutsi soldiers. Tactics of rebellion during his tenure included “a heavy reliance on the use of drugs and magic; in each case the attacks were conducted in the most indiscriminate fashion, and were accompanied by senseless cruelties; and in each case violence took place within a very rudimentary organizational framework…many of the Burundi rebels sought sustenance in hemp smoking, and invulnerability to bullets through resort to magic. Some were identified as wearing white saucepans stained with blood as helmets, their bodies tattooed with magic signs as immunity against attacks." It is crucial to note that these rebels included both military men and civilians. The Tutsi army immediately fired on the rebels and killed as many as 2,000 in the initial stage, with the province of Bururi claiming the heaviest losses. As the rebellion continued, at least 2,000 more civilians were killed. Ndadaye was also assassinated a few months later by Tutsi army officers. (Prunier, 2008, Pg. 39).

Similar to Burundi, Rwanda’s history of division between Hutu and Tutsi groups was intensified during colonialism. Prior to their independence, the Belgian colonizer separated Rwanda in the form of a Tutsi monarchy and a Hutu peasantry, similar to Burundi. In A History of Genocide in Rwanda, Lemarchand (2000) mentions that the monarchy was given orders by the colonizer to victimize Hutu masses. Tensions were already high among both groups prior to the colonial period, however, they became more apparent by the constraints and discriminations introduced by colonial overrule. One method of agitation by the colonizer was to alter the way that Tutsis thought of themselves. The colonizer categorized them as a different race from their Hutu counterparts. Lemarchand states, “Under Belgium rule Tutsi identities were radically altered by racial myth, the Hamitic myth that tended to turn Tutsi into settlers, thus setting in motion a settler/native dialectic which reached its horrendous climax in a genocidal apocalypse.” (Lemarchand, 2000, pg. 308).

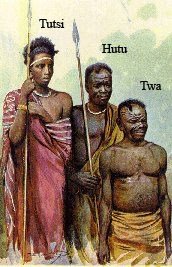

Making an ethnic group believe that they are a different race is a form of agitation that creates external differences. Lemarchand further explains that the Belgian colonizer practically figured that as a political identity, ethnicity marked an internal difference, whereas race signified an external difference. External difference motivates people to fight as similarities between them and their opponents become blurred. The colonizer favored Tutsis over Hutus because Tutsi had somewhat European physical characteristics. The Tutsi ethnic groups tend to be leaner, taller, and have a lighter skin tone. Hutu people tend to be heavier with darker skin tones. The below images shows physical differences between a Tutsi and a Hutu person as portrayed by the colonizer.

In 1995 Mobutu the second president of the DRC, then Zaire, was facing great criticism from the international community especially the United States for ruling the country for 32 years without paving the way to democratic elections. He, therefore, saw the influx of Rwandan and Burundian refugees in eastern DRC in 1994 as an opportunity to show the world that he was capable of ruling the Congo and that re-election was not necessary. In the Massacre of Refugees in Congo: A Case of UN Peacekeeping Failure and International Law, Emizet asserts that Mobutu himself utilized the tension between Hutu and Tutsi groups that migrated to the DRC to cause more conflict and as a result agitate Nande and Hunde groups of the DRC into motivation to chase the Banyamulenge (Hutu and Tutsi groups as labeled by the Congolese) out of the DRC. Mobutu secretly sided with the ex-FAR, the Hutu Rwandan Armed forces and provided assistance to them to overthrow the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Tutsi dominated political and military front. One method of agitation that he used to motivate them was to use posters referring to Tutsi groups as “inyenzi” (cockroaches), a term well known to Hutus that was used widely in their home countries to refer to Tutsis. This further incited the Hutu ethnic group to keep fighting the Tusti group and the RPF.

Emizet further explains that with French support, Mobutu simultaneously ordered his own soldiers to exterminate all the Banyamulenges (Hutu and Tutsi groups from Rwanda and Burundi) including the Hutu ethnic group that he sided with before. He again used imagery to motivateNande and Hunde groups of Congolese origin to unite and fight Banyamulenges inGoma, Kivu and Bukavu regions. Some of the images of the massacres during theconflict between Nande-Hunde Congolese people and Banyamulenge people wereposted on people’s homes to remind them that there was something that needed tobe done and that the Banyamulenge had to leave the DRC for the country to be at peace. (Emizet, 2000, pg 10).

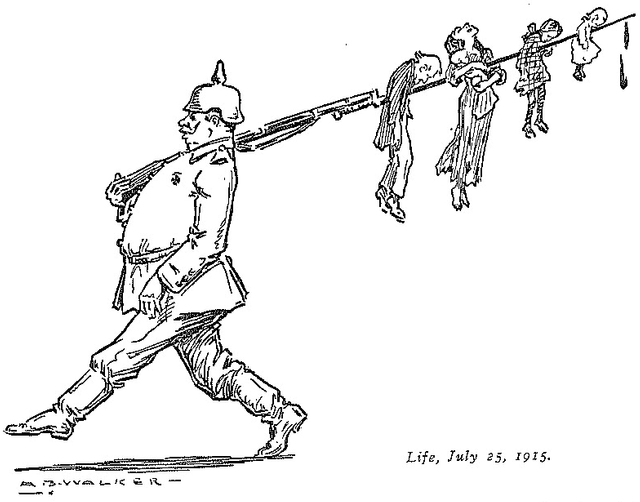

A similar tactic was used during Woodrow Wilson’s appointment in 1916 in the middle of the First World War. In Media Control: The Spectacular Achievements of Propaganda, Chomsky explains that the US population in 1916 were reluctant to get involved in the war, which they perceived as a European war. The Wilson administration however, being committed to war, felt that they had to do something about it. Chomsky states that “the means that were used were extensive. For example, there was a big deal of fabrication of atrocities by the Huns, Belgian babies with their arms torn off, all sorts of awful things that you still read in history books.” (Chomsky, 2002, pg. 8). According to Chomsky, the propaganda of dead babies and other atrocities succeeded in turning a pacifist population a“hysterical war-mongering population which wanted to destroy everything German, tear the Germans from limb to limb, go to war and save the world.” (Chomsky,2002, pg. 7).

The Ways that media and Integration Propaganda fueled ethnic conflict in Rwanda, Burundi and the DRC:

As mentioned earlier, politicians often immediately apply integration propaganda after they have gained power though propaganda of agitation. In most Central African ethnic conflicts, integration propaganda is mostly used to remove doubt or guilt from the dominant oppressing group and therefore further encourage them to adhere to the politician’s desired patterns. It is also used as a way to lead the subordinate oppressed group into non-action by accepting patterns set up by politicians.

Following the quick removals of Hutu politicians by Tutsi military leaders, the Hutu ethnic group has become less resistant to Tutsi insurgency and most have preferred to flee than to fight from the year 2000 until now. In Explaining the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, Hintjens (1999) explains that after the assassination of Habyarimana in 1994, more or less pristine theories of racial struggle and racial hierarchy became activated and politically charged during a period of severe economic and social stress. (Hintjens, 1999, pg. 242). After gaining power in 2000, Paul Kagame has advertised to a great extent the social conformism and obedience of Rwandans. This psychological message implies that there is a Tutsi superiority that must be accepted for there to be less chaos in the country. Obedience in the Rwandan social setting also alleviates guilt from Tutsi groups who may feel some kind of remorse towards their Hutu counterparts. Instead of seeing themselves as terrorists, obedience and conformism allows them to view themselves as patriotic citizens following set patterns by the president.

In addition to obedience, Kagame has further reinforced the racial divide set by the colonizer and continues to advertise that Tutsis are a different race from Hutus. The distinction in physicalappearance and genetics, although stark at times, is not always the case. Hintjens further states that, “Since at least the 1950s, average Batutsi and Bahutu [“ba” referring to a group of people in most Bantu languages] have been identical in the language they speak, in their religious beliefs, in their educational and income levels, and in the acres they farm and the number of children they bear. Both in height and looks, differences between Bahutu and Batutsi are not as clear-cut as most historical and anthropological accounts suggest.” (Hintjens,1999, pg. 242). In fact during the genocide in 1994, mistakes were reported to have been made as several mixed marriages had occurred before the genocide and continue to occur. Most of the tension originated from clashes between the Rwandan Patriotic Front(Tutsi) and the Rwandan Armed Forces (Hutu). Yet, during and after the genocide many local civilians even those who were living in harmony were propagated to side with a group. The 1994 genocide in Rwanda claimed an estimated 500,000-1,000,000 lives. (Hintjens,1999, pg. 247). After the genocide, however, more and more Hutus have become less resistant to Tutsi leadership. Some have decided to flee to neighboring countries while others have remained in the country and continue to be persecuted by the Rwandan Patriotic Front.

Burundi also experienced similar integration propaganda at the hands of politicians after gaining political office. As mentioned earlier Habyarimana utilized radio stations to propagate the message that Tutsis were cockroaches that had to be crushed. This agitated people to fight and lead to genocide in 1993 until he was assassinated in 1994. Right after becoming president in 1973, Habyarimana’s method of integration was the promise of national unity. (Shah, 2006, pg. 2). As a newly appointed president, Habyarimana implemented many reforms, such as modernizing the civil service, making clean water available to virtually everyone, raising per capita income, and seeing an inflow of money from Western donors. Not long after that, two or three years later, his method changed to absolute totalitarianism. Anyone who dared to oppose his orders was publicly executed in the countryside as an example. Once he sensed a great amount of resentment from the opposition or Tutsi ethnic group, Habyarimana’s method of integration changed to democratic by allowing the political opposition to assume government posts, while simultaneously secretly establishing death squads within the military. This strategy lasted him 11 years in power until he was assassinated in 1994. (Shah, 2006, pg. 4).

Sentiments of racism and prejudice in Rwanda can be found even today. In the era of social media, hutu groups have taken to social media to continue to insult Tutsis and call them cockroaches. Below is a tweet in French where a member of the Hutu ethnic group requests that "Frodebu show patriotism to those cockroaches."

Sentiments of racism and prejudice in Rwanda can be found even today. In the era of social media, hutu groups have taken to social media to continue to insult Tutsis and call them cockroaches. Below is a tweet in French where a member of the Hutu ethnic group requests that "Frodebu show patriotism to those cockroaches."

Unlike politicians in Rwanda and Burundi, Mobutu’s method of integration did not require much effort. Although he used imagery to agitate the Nande-Hunde people to fight against the Banyamulenge, he did not put as much effort to get people to side with him. Part of the reason was that Mobutu was a well-respected leader in much of Africa despite being a dictator for 32 years. Another part of the reason was that he had plenty of supporters from the international community which made him someone to fear. As Chomsky notes, while responsible men question how they can get into a position where they have the authority to make decisions, they serve people with real power to get there. Mobutu understood this very well. He spent his presidency feeding the values and interests of Western countries and the state corporate nexus that represented it. Once he started looking into feeding power of his own interest, he was sent into exile in 1997.

Much effort was however put in during the beginning of his presidency when he was trying to gain people on his side. One example is when he changed his name from Joseph Desire Mobutu to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, loosely translated as "The all-powerful warrior who because of endurance and will to win, will go from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake." In addition to changing his name, he also changed the country’s name from Congo to Zaire, which means River or the earth. Furthermore, he designed the flag of Zaire to portray a man of the earth carrying a burning torch while enduring the sun. His national symbol was designed as a leopard overlooking justice, peace, and work. Much of this imagery incited fear in people in Zaire and neighboring countries. Mobutu structured the beginning of his presidency on the fact that Congolese people wanted a tough leader who would save them from the hands of the colonizer.

Because Mobutu had established his presence earlier on during his tenure, it was very easy for him to get people to follow set patterns even without using terror. Mobutu’s very presence became of a form of integration propaganda. His costumes were made of leopard print and he started most of his speeches with “Mobutu awa, Mobutu Kuna, Mobutu partout,” loosely translated to Mobutu here, Mobutu there and Mobutu everywhere to imply that he saw everything. During the 1995’s influx of refugees from Rwanda and Burundi into the DRC, no one dared to oppose Mobutu. His orders were followed throughout the country, confusing people to fight against one another while he remained in power. His demise came in 1994 when the United States ordered him to leave the DRC in 1997. He silently traveled to Morocco where he died of prostate cancer. (Wrong, 2000, pg. 104),

I posit that propaganda and social media in Central Africa should be used as a means that should aim to change people’s minds for positive goals such as forgiveness and reconciliation and sharpen their focus to lead them to take action on these positive goals. One group that has utilized social media for positive results is the group “ To Sangana,” a facebook community that seeks to reunite Congolese tribes through theater and dance. Congolese musicians of different tribes have also come together during and immediately after Laurent Kabila’s death to sing about reconciliation in several different languages of the DRC. One example is the song Hommage a Mzee Kabila which calls for people to have a Congolese identity rather than an ethnic one and build the country as one people. Many Rwandans have also utilized videos to advocate forgiveness and reconciliation. A lot more have also taken to social media to advocate reconciliation even if sentiments of conflict and ethnic superiority still persist after years of negative propaganda by greedy dictators.

References:

Chomsky, N. (2002) Media Control: The Spectacular Achievements of Propaganda.

Seven Stories, pp. 5-58Conrad, J. (2007) Heart of Darkness and The Congo Diary. New York: Penguin Classics.

Emizet, N.F.K (2000). The Massacre of Refugees in Congo: A Case of UN Peacekeeping

Failure and International Law. The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 38, No. 2, 163-202. Retrieved from JSTOR Database.Ellul, J. (1965). Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. New York: Vintage.

Hintjens, H.M. (1999). Explaining the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda. The Journal of Modern

African Studies Vol. 37, No. 2, 241-286. Retrieved from JSTOR Database.Lemarchand, R. (1975). Ethnic Genocide, African Studies Association, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1-16. Retrieved from JSTOR Database.

Lemarchand, R. (2000). Review Article: A History of Genocide in Rwanda, The Journal

of Modern African Studies Vol. 43, No.2, 307-11. Retrieved from JSTOR Database.Mwakikagile, G. (2001). Modern African State: Quest for Transformation. Nova Science

Publishers, Inc.Plouffe, D. (2009). The Audacity to Win: The Inside Story and Lessons of Barack

Obama's Historic Victory. Viking.Prunier, G. (2008) Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making

of a Continental Catastrophe. New York: Oxford University Press.Shah, A. (2006). Media, Propaganda, and Rwanda. Retrieved on 16 December 2013 from

web: http://www.globalissues.org/print/article/405Taylor, P. (1995). Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda from the Ancient

World to the Present. Manchester University Press.Wrong, M. (2000). The Emperor Mobutu. Transition. Vol. 9, No. 1, 92-112. Retrieved

from JSTOR database.

Hello, I'm Oatmeal Joey, and are there dinosaurs in Africa?

Hi Oatmeal Joey. There are currently no dinosaurs in Africa.

Maybe some dinosaurs hiding in the Congo. You know the jungles are pretty big and there are parts of the jungles that may not have been explored in many years or ever.

Could be. It would be cool to have dinosaurs in the Congo.

Only thing better than dinosaurs are girls.

the found some dinosaur fossils in egypt today

Wow, awesome. Do you have the article?

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/01/new-egyptian-dinosaur-africa-europe-asia-cretaceous-spd/

Awesome. Thanks!