The Philosophy of Physics: What is Space? – Episode 1

Reaching a sufficient understanding of the nature of Space and time has been an everlasting problem. Leibniz and Newton, both great pioneers of Science, have devised ideas to explain what Space actually is. Newton backed the Substantivalist theory; a theory that Space is merely a container containing material, where this container itself is also a physical entity, as well as the bodies that it contains [1]. In other words, all the objects you see around you are objects contained within this container that we call Space, that is also a physical object. Leibniz, on the other hand, opposed Newton’s theory and argued that this container does not exist. He believed Space is explained simply by the spatial relations between material bodies [2]. This ideology was aptly named Relationism. Both theories have convincing arguments explaining why they are correct, but in this article, I will be supporting Newton’s Substantivalist view by assessing various arguments based on experiment and settling with a conclusion.

Substantivalism: The Rotating Bucket Argument

Having made countless discoveries regarding inertial and non-inertial motion throughout his life, there is no surprise that Newton chose to support a Substantivalist view as opposed to those of a Relationist [2]. He crafted an experiment entitled ‘The Rotating Bucket Experiment’ in order to disprove Relationism. I shall explain in depth what this experiment is, how it attempts to disprove Relationism and some of Relationism’s opposing arguments made in attempt to counteract those of a Substantivalist.

What is it?

The rotating bucket argument is a simple and easily carried out experiment that starts off with a bucket of water being hung from a rope, in space. It is this simplicity that makes this argument so eloquent as the outcome is undeniable even to someone who has no concept of the laws of Physics, just from observation.

The Experiment

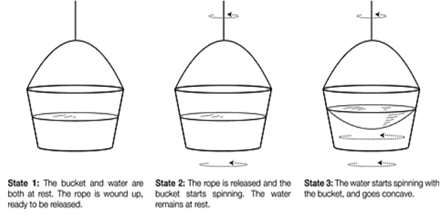

The aforementioned rope is wound up until twisted tight, held (to ensure the water is static) and released. From this experiment, three important observations can be obtained. Firstly, the bucket and the water both appear to be at rest before release. Secondly, the bucket begins to spin upon release; with the water appearing to still be level and at rest. Thirdly, the water starts to co-rotate with the already rotating bucket, causing the water to recede from the centre and travel up the sides due to the forces imposed on it, thus forming a concave shape [3]. This is shown in figure 2 below.

Experiment Observations

The concave shape formed is due to the acceleration of the water with respect to absolute acceleration of space and is of great significance in putting together the Substantivalist argument. Why? Well, from a Substantivalist point of view, any motion is relative to absolute space. In other words, all bodies move relative to an absolute acceleration of space; where the definition of ‘space’ is that defined by the Substantivalist, mentioned in the introduction. This is all bad news for a Relationist; as motion in Relationist terms must be relative to another material object. Considering: a) the water does not rotate with the bucket as soon as the bucket is released and b) the water begins to accelerate for some time after the bucket is released, eventually forming a concave shape, as shown in State 3 in figure 2, implies the water cannot be spinning relative to the bucket; it is in fact accelerating relative to absolute space. This is because once the rotating bucket reaches ‘State 3’, the speed of the water is the same as that of the bucket, meaning from the bucket’s frame of reference the water is not moving and from the water’s frame of reference the bucket isn’t moving. At this point they are not moving relative to each other. If the movement of this water is not relative to the bucket, what can it be relative to? This is answered by the notion of acceleration of absolute space which is inherent to a Substantivalist’s concept of the container of space.

Relationism’s opposing arguments

Since the motion of a material object should be relative to another material object, from a Relationist point of view, there are no doubts that an argument was to be constructed to oppose this Substantivalist theory. The Relationist may argue that the water is rotating relative to a fixed object in the room, for example a chair; but remove said fixed object and you are left with an invalid argument as the water still behaves in the same manner. In a better attempt to bridge the gap, Ernst Mach, a Relationist physicist, used the ‘fixed stars’ argument to explain why the water was not moving relative to the bucket. He states that the Earth’s rotation is relative to the motion of Stars surrounding it [2]. In other words, if we took all material bodies out of the Universe and left just the spinning bucket, we would have no way of knowing how this spinning bucket would behave. In an empty Universe, the bucket and water would appear at rest, even though both are rotating. Essentially, Mach suggests that it is not the motion of absolute acceleration of the Universe that causes the water to act in this abnormal manner, but in fact, it could be the celestial bodies of outer-space. We have no way of knowing the impact of such bodies on this experiment, therefore who’s to say that they weren’t the cause of the motion of the water? However, this doesn’t sufficiently disprove the notion of absolute space, it just picks a small loophole in Newton’s theory.

Summary

Unlike Relationism, the effects of inertial forces can clearly be explained by Substantivalism, in this experiment. Although the ‘fixed stars’ argument picks a significant hole in a Substantivalist view of Space, it doesn’t provide an alternative, definitive explanation from a Relationist stand point, for the motion of the water. The only way the argument would be definitive, is if the hypothetical ‘empty Universe’ can be possible; which it cannot. As a result, one can conclude that Relationism fails to fully counteract and explain the Rotating Bucket ideology.

Coming up in Episode 2…

In this episode I have spoken about Substantivalist views of the nature of Space; i.e. it being a container containing material bodies. In the next episode, I will be discussing the nature of Space from a Relationist point of view.

If you have any questions, leave them below and until next time, take care.

~ Mystifact

References:

[1]: https://minerva.leeds.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/

[2]: Sklar, L. 1992. Philosophy of Physics. United States of America: Westview Press.

[3]: http://images.slideplayer.com/16/5235889/slides/slide_13.jpg

Please note; no copyright infringement is intended. All images used have been labelled for re-use on Google Images. If any artist or designer has any issues with any of the content used in this article, please don’t hesitate to contact me to correct the issue.

Relevant articles:

Our Solar System, Our Home

Will Teleportation Ever Be Possible?

Can We Download Our Brains and Live FOREVER?

Previous articles:

How to Turn a Traffic Light Green

Where Does Burnt Fat Go?

How Do Touchscreens Work?

Follow me on: Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and be sure to subscribe to my website!

Clearly monads are the way to go.

Really wonderful contest you are a really successful person

Interesting read, thanks for this, I'll read on to episode 2 :)