Philosophy Introduction and Chapter 1

Note: This book was first published for the Kindle platform in 2013. It is also available on a free Wix site here: http://tomblackstone1.wixsite.com/whyweneedphilosophy. Over the next few months, I will be periodically re-publishing its chapters to the immutable Steem blockchain.

Eventually, the entire book will be available on Steemit. For this reason, it will still be available in the event that Amazon.com and Wordpress become unable or unwilling to carry it on their servers.

Philosophy: What It Is and Why We Need It

By Tom Blackstone

Copyright 2013 – Tom Blackstone and Benevolent Universe Publishing, Second Edition

“What is the point of studying philosophy? Will it help me to get a job? Will it make me more money? Can I use it to gain a greater station in life and more respect in the world? And what is philosophy? Isn’t it just a bunch of crazy people who think that reality doesn’t exist and we can’t know for sure whether we are conscious? Isn’t philosophy just a matter of opinion? Why bother with a subject that can’t give us any real knowledge and which is always disputed?”

These questions are typical of the attitude of the average person who has never studied philosophy. To the uninitiated, philosophy seems to be a subject that has very little relevance to the problems and concerns of every day life. Knowledge of philosophy is not something that most employers are looking for; neither is it a thing which gives a person great respect in the world: scientists, engineers, and doctors are far more loved in our society than philosophers. And although studying philosophy can be fun, it is also a lot of work and is certainly not very relaxing. If one is looking for a way to calm oneself after a hard day’s work; music, video games, and television are better things to concentrate on than philosophy.

And yet, philosophy is a subject that has been written about and argued over for thousands of years. Many philosophers have been imprisoned or even killed for the things that they taught. In other cases in the past, philosophers have been held up as positive examples to the rest of society. Why has such a seemingly useless subject had so much of an influence on history?

Were previous generations making an error when they paid so much attention to it? Or is there something wrong with our society today? Is philosophy really a subject filled with bizarre theories that have nothing to do with real life? Or is it something else, something extremely valuable and yet relatively unknown? These are the important questions which I hope to answer over the course of this book.

In order to know what philosophy is, we must first understand its history: how it arose, what purpose it was believed to have served, in what ways it developed over time, and how it came to its present state. In order to know whether philosophy is useful to us, whether it is capable of giving us genuine knowledge of the world around us or whether it is instead simply a mish-mash of arbitrary opinions that clash with each other endlessly and is therefore of little value, we must first know what it is that philosophy teaches. We must know what the theories are that are alleged to be arbitrary, irreconcilable “matters of opinion” before we can know whether it is truly impossible to decide between them. Only then can we decide if philosophy is or is not useful to human beings.

My own view is that philosophy is the study of the fundamental nature of the Universe, of human beings, and of human beings’ relationship to the universe, through the use of reason, and that it is vitally important to human life. My justification for this view is that it is the only understanding of the subject which is consistent with both its history and the current practice of its most convincing advocates.

I argue that the current popular view of philosophy as a debating society which has little to no relevance to practical, every day life is itself a product of false philosophical theories. These false theories became popular in universities in modern times because of the inability of earlier philosophers to deal with the arguments made in favor of them.

However, these arguments have now been answered by a new tradition in philosophy that began outside of the university system and is still not accepted within it. The tradition I am referring to is Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism. Although Objectivism has become extremely popular amongst students in the last ten years, it is still not granted the respect it deserves amongst professors of philosophy. In my view, it is this lack of respect for Objectivism that is the cause of the continuing inability of philosophers to command the attention of the average person.

If this were only a problem for philosophers, it would not be worth writing a book in order to combat it. But this book is not written for the benefit of philosophers. It is written for the person who has come to doubt that philosophy is worth studying.

The person who turns away from the great questions of philosophy on the grounds that there are no objective, rational answers to them is putting his own life and happiness at a great risk. Questions like “What is goodness?”, “How should I live my life?”, “How do I know what is true and false?” and “What kind of universe do I live in?” are not questions that can be brushed aside without consequences. In order to live, a person must decide on an answer to these questions. His only choice is whether he will consciously decide to determine , based on his own rational judgment, what the truth is or whether he will simply accept whatever he is told by the authority figures in his society, regardless of how irrational or self-destructive are the things that he is told. Every human being owes it to himself to investigate these questions and to make up his own mind about them. To do otherwise is to give up on having the best that life can offer and to accept instead a life that is less than ideal.

For this reason, it is necessary to defend the idea of philosophy as a field of objective knowledge against its modern critics, and this means defending Objectivism, a “rogue” philosophy, against its critics in academia. However, this book is not simply an explanation or defense of Objectivism. There are other books written with that purpose in mind which do a much more thorough job than this one. Although Objectivism is discussed in detail in this book, so are many other philosophies such as Kantianism, Utilitarianism, Logical Positivism, etc.

The purpose of this book is to introduce the reader to the grand debates that go on in the world of philosophy and to justify further study in the subject. Even a reader who is not convinced of the truth of Objectivism should come away with genuinely valuable knowledge by the time he finishes this book.

This book begins by tracing the history of philosophy from its origins in Ancient Greece to its contemporary form in universities all over the world. It then continues by discussing some of the most important questions of philosophy, starting with the most practical “What is goodness?” or “How should I live my life?” and continuing into deeper questions like “How do I know what is true?” and “What is the nature of reality?” I will argue that philosophy can provide us with objective, rational answers to these questions. These answers may not be susceptible to the kind of proof we find in mathematics or the physical sciences. Yet, by considering all sides of a philosophical issue, we can come to conclusions which have good enough evidence to support them that we ought to believe in them.

But first, before we consider these issues, let us go back to the very beginning of philosophy. In fact, let us go back even further, before there was any philosophy at all, at the dawn of humanity. . .

Chapter One:

Philosophy’s Precursor, Ancient Religion

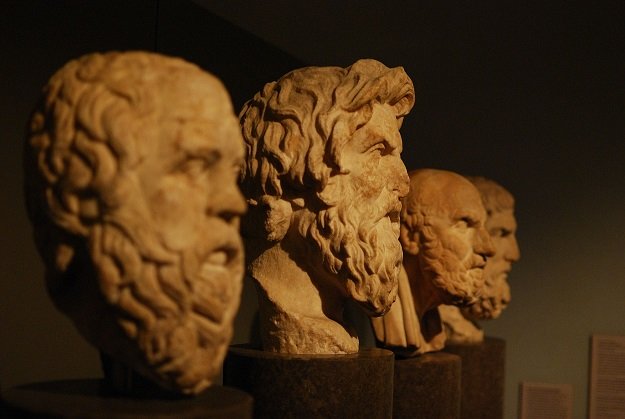

Philosophy first came into existence around 2,600 years ago, in Ancient Greece. But long before then, human beings were creating systematic explanations of the world around them. The need for such explanations was obvious, even to the most primitive humans.

The world that these early humans inhabited was filled with chaos. Clouds would form and rain would fall at random moments. Sudden earthquakes and floods could destroy entire communities. Diseases would kill hundreds of people with no warning at all. At times, the Universe seemed to be subject to the capricious whim of an unknown power.

Over time, every human society was faced with the need to make sense of this seemingly incomprehensible world. And in each case, a set of stories evolved and was passed down from generation to generation, explaining the origin and nature of the Universe.

These stories portrayed the Universe as a product of one or more conscious beings who controlled it. These beings were similar to humans in that they were prone to feelings of joy, anger, jealousy, and even remorse. They, through their control of natural events, held the fate of human beings in their hands. For this reason, the attempt to please these “gods” held a central place in human existence.

But these stories and the practices that sprung up around them, which we call “religion”, did more than simply try to make sense of the chaotic hand of nature. External threats, the “acts of the gods” in the form of natural disasters were not the only threats that human beings faced. They also had to contend with internal, psychological dangers. Fear and sadness could paralyze a person and prevent him from achieving a goal that was necessary to his life. Anger could cause him to act rashly and put himself in danger. Desire could place him in conflict with others and lead to dangers which he had not foreseen.

For this reason, human beings needed a set of principles that would allow them to act for their long-term interests, as opposed to acting for short-term, emotional gratification. The moral codes advocated by these ancient religions provided human beings with such a set of principles. A cursory glance at just a few of these systems of belief provides evidence of their great value to humans.

In the Indian religion of Hinduism, for example, the chaotic world that we see around us has been understood as inhabited by a myriad number of gods which control every aspect of it. However, all of these gods and the entire material world are seen ultimately as an illusion. According to this view, the world we see around us is nothing more than a manifestation of a deeper reality, known as “Brahman”. Brahman, true reality, is to be contrasted with “Maya”, the world of the senses. Human beings are urged to seek escape from Maya and to reunite with Brahman. They can do this by living moderate lives and refraining from unnecessarily harming others. This will allow them to escape the cycle of rebirth that has caused them to be reincarnated into the world of Maya each time that they die. By escaping the world of Maya, they will be free of the pain and misery that accompanies it. Thus the chaotic, seemingly incomprehensible world of the senses is explained by a deeper order that lies beneath it and human beings are given guidance as to how to avoid the suffering that they are confronted with.

In traditional Chinese religion, the world is inhabited by ghosts of the ancestors of all human beings^1. These ghosts have the power to intervene in human affairs, to heal diseases and to prevent natural disasters. However, in order to please these ancestors, a person must live a morally upright life. He must work at a useful occupation and not cause discord in the society around him. By doing so, he is acting in accordance with “the will of Heaven” and will, therefore, find peace and happiness on earth. Thus, both the natural world and the place of humans within it are explained.

In the ancient Hebrew religion of Biblical Judaism, the Universe is the creation of and ruled by one God, called “Yahweh”, who has made a pact with human beings in which he has agreed to grant them prosperity in exchange for obedience to his commandments. His commandments include a prohibition against murder and dishonesty, amongst other things. In this way, Biblical Judaism attempts to make sense of the world and to provide human beings with guidance in their lives.

There is no question that these religions, and others like them, provided great value to early humans. Today, millions of people still live entirely by the guidance of these systems of belief, without having studied philosophy at all.

But there are good reasons why a modern person should pause and question whether these religions can provide all of the answers to the fundamental problems of human existence. Although good arguments can be made for the value of a code of morality to guide human beings in their lives and for the idea that ancient religions do provide some aspects of such a code, there is also evidence that they often fail to provide adequate moral guidance. In some cases, they even advocate things that any reasonable person would have to conclude as being immoral, since they lead to the oppression of certain groups of people.

For example, under ancient Hinduism, society is divided into four rigid, hierarchical castes. At the top of the social hierarchy are the Brahman (priestly class). Below them are the Kshatriya (warrior class), Vaisya (merchant class), and Sudra (servant class). At the very bottom of the social ladder are the “untouchables” who are considered caste-less. A person born into one caste cannot move into another, no matter what his accomplishments. At least, he cannot do so in this life. Members of the lower castes are cut out of the wealth and influence of the higher castes, with the “untouchables” being treated so badly that they are often regarded as little more than animals. When asked how to justify such a state of affairs, a traditional Hindu will reply by saying that a person will not be born into a lower caste unless he has done something immoral in a previous life. Thus, according to this view, it is just for him to suffer for his past transgressions.

In traditional Chinese religion, we see similar attempts to oppress and control certain groups of people. Children are required to obey their parents even into adulthood, women must adopt subservient attitudes towards men, and subjects most obey their rulers no matter what. To do otherwise is to not act in accordance with the will of Heaven and is to bring shame upon one’s ancestors.

In Biblical Judaism, we see similar attempts to justify oppression, with exhortations to put homosexuals to death and to massacre entire cities of people, including women and children^2.

Modern advocates of these religions often argue that these oppressive doctrines are no longer taken seriously by current practitioners. To a certain extent, they have a point. In practice, modern versions of these religions do tend to be less oppressive than they were in the past. However, these religions have become less oppressive precisely because human beings have stopped blindly believing in everything that they say. It is because human society has become more rational, objective, and philosophical that these religions, at least in their traditional form, have begun to have less influence in the world.

And when we speak of things becoming more “rational” or “objective”, we come to the heart of the issue. All human beings lie within the same Universe. We all breathe the same air and walk the same earth. We survive in the same ways, by hunting and gathering or by planting crops and herding animals. We associate with each other in similar ways: we get married, have children, and build political systems.

Yet each human society has developed a different set of stories to explain the origin of the Universe. Each human society has created a different religion.

These religions differ from each other in profound ways. The Hebrews claimed that there was only one God while the Hindus say that there are many. The Chinese religion does not mention a god but relies on the abstract concept of “Heaven” along with the ghosts of ancestors. The Hindus believe in reincarnation while the Hebrews did not (and the Hebrews’ modern equivalents, Christians and Rabbinical Jews, do not).

Each of the religions that human beings have created contain numerous contradictions with all other religions. Thus, no more than one of them can be true. And yet, there is no obvious

method a person can use to decide between them.

The primary means that religions use to justify their ideas is by appeals to popularity. Hindus in India “know” that Hinduism is true because nearly everyone in their society believes in it. The same is true for Christians in Europe and the Americas, Muslims in the Middle East/Southwest Asia, and Chinese religion in China.

These appeals to popularity are convincing as long as human beings do not learn about cultures other than their own. But the moment a person escapes his ignorance and sees the multiplicity of worldviews that surround him, he begins to wonder if any of these religions can be trusted to answer the most important questions he faces in his life. Religion, to such a person, appears to be something that is merely “subjective”, a matter of opinion; an irrational, arbitrary point of view.

What such a person needs is a system of belief that is objective, that is true independently of anyone’s attitude towards it. What such a person needs is a set of beliefs that are rational, that have good enough evidence to warrant accepting them over every other set of beliefs. It is only such a system that can provide a modern human being with a satisfactory understanding of the Universe he lives in and his place within it.

But is such a set of beliefs possible? Is there such a thing as objective truth? Are there any rational answers to the questions of human existence? Are there moral principles that are not merely arbitrary rules designed to oppress certain members of the populace?

These questions seem to come in an onslaught without end. But there is an end. In order to find it, we must depart from this discussion of ancient religion and begin to consider the birth of philosophy.

#objectivism, #ancientreligion, #whyweneedphilosophy

Notes:

1. Traditional Chinese religion is a combination of Confucionism, Daoism, Buddhism, and certain folk practices native to China.

2. Lev. 20:13, Josh 6:17, 20-21

Steemit is mostly immutable...I believe Steemit Inc. can still take down content if it violates copyright law.

My understanding is that it can still be seen on other web portals if that is the case.

Interesting read...Ayn Rand was never accepted as a philosopher because her thoughts didn't fit the generally accepted narrative which has moved even further from Objectivism. Look forward to reading more.

If you don't want to wait, I left a link to the whole book in .pdf form near the top of the page.

Congratulations @tomblackstone! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCongratulations @tomblackstone! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @steemitboard: