Decartes' Substance Dualism

Descartes refers to the ‘I’ as “in the strict sense, only a thing that thinks. That is, I am a mind.” He calls the ‘I’ the author of thoughts. The body, on the other hand, is not who the ‘I’ is, but rather a thing which the ‘I’ has—or, at the very least a thing which the mind perceives itself to have. “I am not that structure of limbs which is called a human body.” “I ha(ve) a face, hands, arms, and the whole mechanical structure of limbs which can be seen in a corpse, and which I (call) the body.”

By these definitions the mind and body must be two distinct entities. While the body is something the mind has, the mind, Descartes claims, is a doer of things. “(I am) a thing which thinks, … a thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, is willing, is unwilling, and also imagines, and has sensory perceptions.” It then follows that “to be” is “to do”—at least a certain kind of doing.

To doubt, understand, affirm, deny, be willing, or be unwilling one must analyze information. That is, to think is to interact with information. Information must first be received for analysis to occur. Descartes mentions two possible ways to receive information: sense perception & imagination. To sense perceive is to receive information I consider to be real from that which I do not consider to be myself. But, imagining is perceiving what is non-real, that is, to imagine is to take in information which I consider to be unreal from that which I consider to be myself. The doing we call “thinking” is based on either an interaction between a real self and a real non-self or an interaction between a real self and a non-real self. He says, “this puzzling ‘I’ … cannot be pictured in the imagination.” This is because to imagine (or sense-perceive) there must be an interaction with a real self. If ‘I’ were able to imagine a self, it could only be a non-real—as it would be composed of information the real self obtained from a non-real self or a real non-self.

The I cannot be pictured in the imagination.

Descartes’ mind/body dualism is the result of three considerations—namely the epistemic, those of physics, and those of comparison between animals and machines. First he asks what we can know and how much certainty we can claim. The senses deceive. This is because we do not perceive reality itself, but our thoughts regarding reality. “(when I) see men crossing the square … I normally say that I see the men themselves … Yet do I see any more than hats and coats which could conceal automatons? I judge that they are men.” Thus, the senses are filtered through the mind. The ability to discriminate between two things is built up from our past experiences. The senses send a limited range of information—for example, we do not see microwaves, but only visible light waves—our brains compare that information to remembered objects and events, and then tell our minds that we have witnessed a thing which is like a specific set of things in a certain way and unlike other sets of things in certain ways.

If I ask you to think of “apple” without further context, our minds parse through all the things which we have in past labeled “apple”: Granny Smith, Golden Delicious, Honeycrisp, Fuji, McIntosh red, Apple Macintosh, MacBook, iPhone, Steve Jobs, Apple Corps., the Beatles… Your mind accepts that it has perceived these real objects in past and has fit to them the label “apple.” Having no further filtering information, it doesn’t stop on the first one which comes to mind, but skims through all items thus labeled.

Knowledge of the body and its existence relies on imperfect sense perception and the mentioned filtering process. Knowledge of the mental self, however, doesn’t require either. As Descartes says, “It is possible that what I see is not (real) … It is simply not possible that I who am now thinking am not something.” Which is to say, because I am aware of my thinking, ‘I’ at least must exist.

He also discusses that we can be fooled into believing that dreams are reality. So, we cannot be certain that any non-self thing is indeed real. From both of the above he concludes that the mind exists necessarily, while all else—including the body—exists contingently.

Decartes’ third consideration is as tenuous as his second. It is as follows:

① The bodies of men and animals are analogues.

② The physical principles which govern bodies are the same.

③ No matter their mental abilities, men can make their thoughts understood to others through language.

④ Despite having the organs necessary for utterance, animals don’t demonstrate skillful use of language.

⑤ Animals cannot demonstrate what they are thinking.

⑥ ∴ “They have no intelligence at all.”

Descartes also states that human-like machines would be unable to fool people into believing that they are humans. This has yet to be proven false, but Alan Turing described the conditions under which he believed it could be done. Modern programmers and artists have so far been frustrated in their attempts to surmount the “uncanny valley”—the unsettling feeling experienced when people “meet” human-like machines.

Beyond the objections above listed, thinkers since Descarte have rejected his substance dualism. The sciences depend on externally observable phenomena and the mind cannot be observed objectively. This has led to a split in academia. On one side are biologists, psychologists, and most anthropologists stating that we can only scientifically study the objectively true—the physical brain, behaviours, and cultures, respectively—and thus that which is quantifiable. On the other side sociologists and some anthropologists, many of whom reject the concept of objective truth, depend on subjective and qualitative data.

Psychologists focus on behaviour because it is both highly observable—by external agents—and highly manipulable—again, by external agents. It is the most cost-effective and time-effective method for obtaining “mental” data. Moreover, because scientists cannot objectively observe the “mental” or “spiritual”, the terms are meaningless. This leads to a substance monism in which everything has a physical basis.

Attributions

Images:

- "Mind/body dualism" via Max Pixel, CC0: public domain.

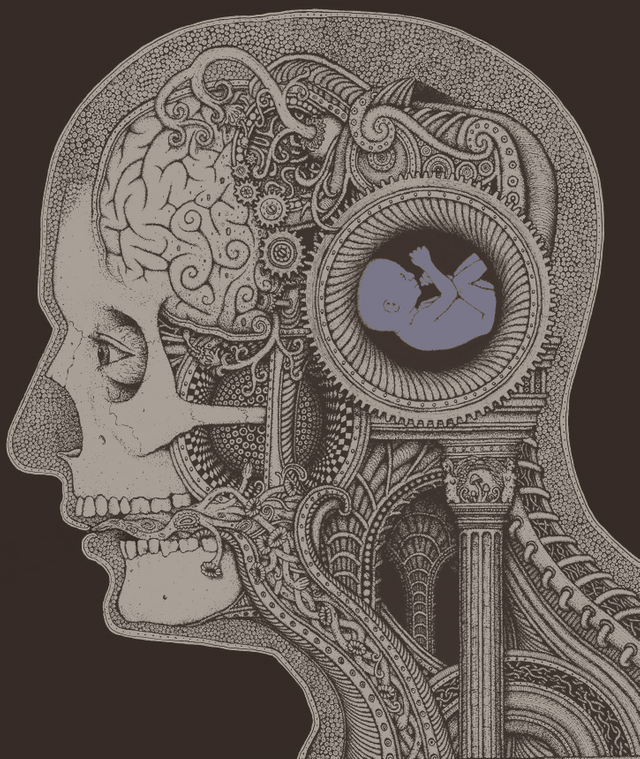

- "Homunculus of the mind" via Soen's Cognitive album cover, modified by article author.

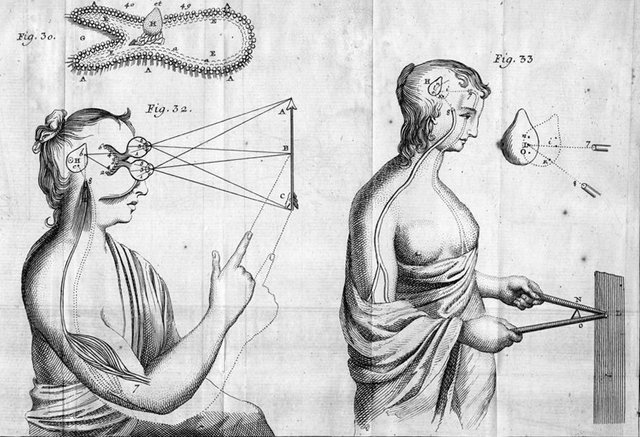

- "L’homme de René Descartes, et la formation du foetus" via Wikimedia Commons, public domain due to age.

- "Kanzi" via Wikimedia Commons (William H. Calvin, PhD), CC Share Alike 4.0 International license.

- "Uncanny valley of the dolls." via PxHere, CC0: public domain.

Quotations:

- Second Meditation & Sixth Meditation from Meditations on First Philosophy in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are demonstrated by René Descartes, 1641

- Part Five Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences by René Descartes, 1637

I use Binance to exchange digital currencies.

I use Coinbase to exchange digital currencies to USD.

Author chooses to invest rewards for this article in the SteemIt platform.

I consider Descartes' cogito to be one of the most ingenious discoveries and undeniable truths in philosophy. And yet it's not considered that way by most, if one may judge from their lack of enthusiasm. If I recall, Thomas Nagel went as far as to claim in a paper that it's a circular argument and so it proves nothing, much less that I exist.

It's worth noting that just because I can doubt something being me, doesn't mean it's not me. It might mean it's not necessarily me (I could have different bodies), but it doesn't mean it's not contingently me (kill this body and you kill me too).

Overall, anything beyond the cogito itself falls into the area of consciousness, and it's a really hard topic. Could robots have minds? Apes probably have minds but do cockroaches have them? How do I know for sure another person is not a robot? Am I just using a kind of 'argument to the best explanation' when I infer that other humans, too, are conscious? Quite tricky topics...

Absolutely! I recently realized a fun argument stemming from these sections of Meditations. If the only thing I can know with absolute certainty is my own existence, and that is a subjective experience, then should we really discount subjective experience as being less descriptive of truth than objective experiences?

Senses fail and dreams can seem real. Hell, we don't even sense the actual thing. As Descartes said, “(when I) see men crossing the square … I normally say that I see the men themselves … Yet do I see any more than hats and coats which could conceal automatons? I judge that they are men.” That is, our minds filter our senses based on past experiences. We cannot trust our senses because all previous experiences could be false (eg., pre-programmed, or experienced only within a simulation).

That's very true: the thing we are most certain about is the thing most impossible to prove objectively. This goes for qualia in general: doctors don't even have a precise objective definition for pain, and usually just have you indicate which emoji printed on a paper describes you more!

I guess the area of phenomenology tries to do what you're saying: put the horse of consciousness back before the cart. But I almost don't know anything about phenomenology so I might be wrong about their intentions.

I guess the reason for not putting consciousness first is because - unless we want public discussion to degenerate back to 'you said VS I said', as is done with religion which leads to fighting and wars - we should only accept as objective truth what can be publicly verified by all. Otherwise what do you say to a person who is quite convinced he is God incarnate?

My own approach to this whole argument that the senses betray us, is to ask "how do you know?", to which the answer is, "well, further inspection by the senses convinces me this is so". So the senses come out back on top.

In other words, I interpret most of these arguments to be of the form: "The senses (in specific occasions) mislead us. Therefore the senses (in toto) cannot be trusted." This is quite uncalled for if you realize that the only reason you know the specific sense impressions are misleading you is because of the senses in toto. The skeptics are, in effect, saying: because the senses (in toto) led me to the truth regarding some cases where I was misled, therefore I cannot trust them. It's like saying "person X showed me I cannot trust person Y, therefore people are not trustworthy". But if you don't trust person X then you don't have any evidence that any person is misleading you. So you need the senses to prove that certain sense impressions are misleading. But if you can prove that, then you can trust the senses.

At any rate, that's the summary of my own pet project in how I intend to deal with this kind of skepticism.

Sorry for the long comment, I tend to be verbose :D

Well, sure, objectivity is the most practical approach, but that doesn't make it the most representative of truth. Similarly, solipsism isn't useful, but is logically sound—or we usually talk about the past and future as actually existing when we can't prove that they are. What this then comes down to is which we value more highly, utility or truth.

Regarding the senses being used to error check the senses, at best we can say that the later sense perception seems more reasonable than the earlier because it is more consistent with what we believe we have previously perceived. The determination is based only on consistency.

If you were to write a piece of code that worked sometimes and not others, you would have to admit that the code is faulty or should be rewritten. You are arguing for writing a second piece of code for finding consistency in the outputs of the first piece of code and then throwing out inconsistent data from the final output. Unless the second chunk is very good you run the risk of undue biases, for example, confirmation bias. For example, both the theist and atheist will remember the experiences that confirm their core belief and forget those which challenge it. The adept programmer would rewrite the first function from scratch to reduce fault points.

Beyond that, there are other means for testing for truth, for examples reason & introspection. Of course, the kicker is that without having boot loaded ourselves based on sense perception experiences early in life, both reason and introspection would have nothing to think about other than the 'I'.

Good reply!

Well I suspect we value believing in other minds and the past and future cos we believe in them, not because there's utility in it. I think we view our inability to disprove solipsism as more of a logical puzzle, like the ones by Zeno of Elea, rather than something to take seriously.

But this just places intuition above logical proof, I guess.

Congratulations @rubellitefae! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCongratulations @rubellitefae! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Man I wish I had a meme to show you how happy this made me