Episode 2: Aristotle's 4 Causes in Biology & Economics

Transcript:

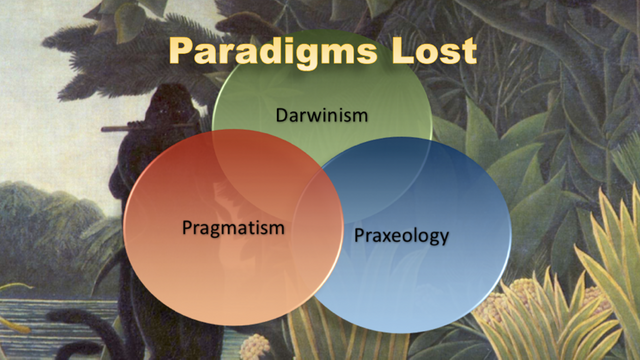

Hello everyone and welcome to episode 2 of Paradigms Lost: A Genealogical Synthesis of Darwinism, Pragmatism and Praxeology. In this episode, I will discuss the (arguably) greatest mind to have ever lived: Aristotle. His understanding of scientific inquiry provides a sort of common ground between the Darwinism, Pragmatism and Praxeology that I wish to synthesize since the inventors of all three schools of thought were extremely well-read in and influenced by Aristotle. This episode will thus focus on Aristotle’s four causes and will point toward the lingering influence that these four causes still have within modern biology and economics.

This episode will build upon the 7th lecture of the series “Great Minds of the Western Intellectual Tradition” by Philip Carey. While the Teaching Company offers several lectures dedicated to Aristotle, I choose Prof. Carey’s for this episode since he is the most explicit about understanding Aristotle from a biological rather than a physical point of view.

The most important step in grasping Aristotle: to pretend that Galileo and Newton never happened. We should thus resist seeing the natural world in terms of atoms in meaningless mathematical motion. This was actually the view of the Atomists who Aristotle was specifically trying to refute!

Instead, we should see the natural world as being populated by chairs, houses, people, crops, animals and all the other things around us that have a purpose or function built into them in any sense. (click) We moderns typically take Newtonian physics to the be the paradigm of natural science and then see biology as a special case of physical matter in motion.

Aristotle, by contrast, almost reverses this assumption by taking the functional objects of engineering and biology to be the naturalistic rule against which meaningless matter in motion is a kind of degenerate exception.

Aristotle thus saw purpose or teleology everywhere in the natural world such that nearly everything had some end-purpose or function. For example, just as the teleological end of a heart is to pump blood and that of legs is to walk, he would also say that the teleological end of stones is to fall towards the earth and that of fire is to rise up towards the sky. These are all the teleological ends towards which each object or process naturally and - non-accidentally - tends or culminates.

Our modern concept of “potential energy” would probably be the closest, Newtonian equivalent to what Aristotle had in mind: Heat differentials or chemical reactions naturally and non-accidentally seek to minimize their “potential” energy. Thus, for Aristotle different things had different potentials which they naturally realized - unless something interfered with the actualization of that potential.

Remember, Aristotle is still considered to have been one of the greatest biologists, logicians and political theorists to have ever lived. It would be a grave mistake to see him as anything less than the genius that he truly was.

With this biological default in mind, we can now discuss his doctrine of the four causes. Aristotle thought that an understanding of the natural world requires us to answer the 4 questions that correspond to his four causes:

i. What material is the thing made of?

ii. What form did the material take?

iii. How did the material take its form?

iv. For what purpose did the material take its form?

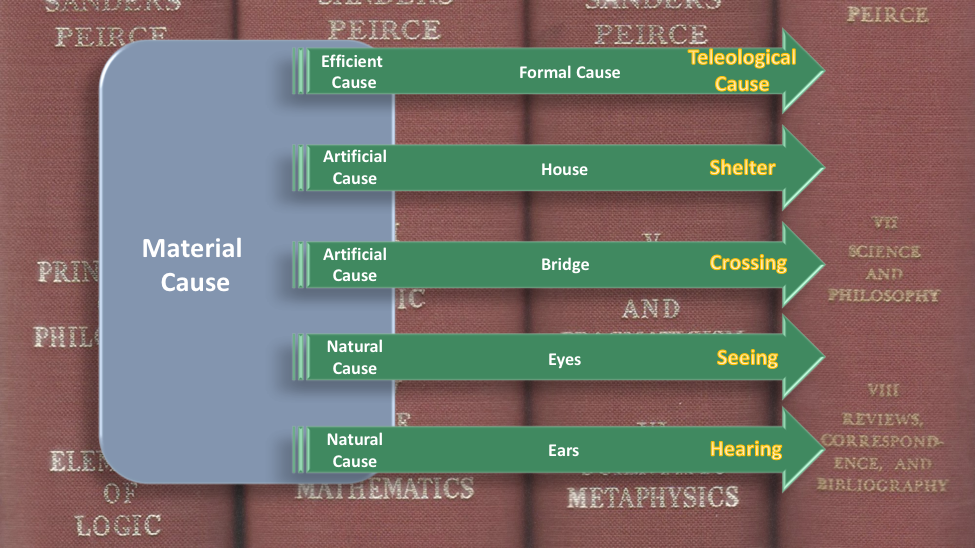

(1) The material cause answers the question: What is the thing made of? For example, (click) houses can be made of either stone or wood, both men and dogs are made of flesh, and so forth. While everything must have some material cause or another in order for it to naturally exist, we must not follow the atomists in thinking that there is nothing more to a house than the wood that its made out of. Indeed, Aristotle would probably say that the material cause is the least informative of his four causes – in stark contrast to the atomists who he opposed.

(2) The formal cause more or less corresponds to our understanding of a definition of something and answers the question: What type of thing is it or what form did the material cause take? As noted, the same material cause can give rise to very different types of forms. (click) Houses or bridges can be made out of stone or wood. (click) Flesh can take the form of eyes or ears. And so on. The main point is that our understanding of the formal cause or definition of “house” can never be fully reduced without remainder to an understanding of “stone” or “wood”. While Aristotle is definitely a materialist of sorts, he is absolutely not a reductionist.

(3) The efficient cause answers the question: How did the material cause take on the formal cause that it now has? While this cause is the closest to what we moderns mean by the word “cause”, we must be remember to take a teleological science like biology as our default understanding of causation rather that of modern physicists. While Aristotle did indeed say that one billiard ball bumping into another was the efficient cause of the second balls movement, it would be misleading for us to take this as a paradigm case.

What Aristotle has in mind, rather, is “what brings a form into existence?” a question which is primarily concerned with a creative or developmental process that relatively little to do with Newtonian physics. An efficient cause thus seeks to explain the bringing into existence of a form from its material cause that previous had no form.

Efficient causation thus comes in two flavors: artificial and natural.

- An artificial cause is when the efficient cause lies is the external action of an artisan or artist. How did wood come to be shaped into a house? An external artisan built the house out of the wood. The realm of conscious human action and engineering are the paradigms of artificial causation.

- A natural cause, by contrast, is when the efficient cause is internal to the form in question, as in the case of biological functions: Eyes, ears, leaves, roots and dogs all come into existence naturally without any of the outside, artificial inference that houses and bridges need in order to come into existence.

Again, I should reiterate that Aristotle did see physical motion as a case of natural causation. I’m convinced, however, that if he were alive today, he would absolutely draw a distinction between the meaningless motion of billiard ball mechanics and the creation of ears from amino-acids. In other words, I think he would grant that Galileo and Newton are right about meaningless motion of brute, physical matter, but not about the creation or development of functional organs and organisms.

(4) Finally, the teleological cause answers the question: For what end-purpose or reason did the efficient cause give form to the material cause? In the same way that (click) houses are built to shelter people and bridges are built to cross rivers; (click) eyes are for seeing and ears are for hearing. In all such cases, the teleological cause is the culminating end or purpose for the sake of all the efficient cause happened. In other words, the teleological cause explains the efficient cause in that if eyes could not see, or if houses did not shelter people, they would have never come into existence in the first place. It is only because of the teleological cause that the efficient case happens at all. An efficient cause that gives form to matter without some teleological cause is, by definition, an accident – and Aristotle’s position is almost defined by its central claim that neither eyes nor houses come into existence by accident.

This was Aristotle’s main objection to the atomists who rejected all teleological ends and were thus forced to see nature as one accidental event after another. Imagine a biologist trying to explain eyes, without the prior, guiding assumption that their “purpose” is to see things. The same logic applies to the case of artificial causation: It is precisely because a builder first seeks to shelter people (the teleological cause), that he only then gathers wood (the material cause) and actively shapes it (the efficient cause) into a house (the formal cause).

In contrast to mechanistic physics, an Aristotelean approach to the biological and the social sciences insists that we must understand material, formal and efficient causes in terms of their respective teleological causes and not the other way around. This position has been strongly contested within both types of science. In the biological sciences, this teleology-first approach is called Adaptationism and lies at the heart of the recent “Darwin-wars” between Daniel Dennett and Stephen Jay Gould. Within the social sciences, this disagreement essentially defined the differences between Mises’ Praxeology and the Behaviorists. The issue at stake in these debates has been whether the methods of biology and economics should be Aristotelean or Galilean in nature.

As a final note, I should also point out that Aristotle thought that his 4 causes were all qualitative in nature thus requiring a qualitative analysis. Aristotle thus saw relatively little use for mathematics in understanding the natural world. Again, think of the limited use that mathematics has to play in paleontology in comparison to chemistry or physics. This naturally raises the question of how well mathematical methods in economics can be used to analyze qualitative economic action?

Alright, I want to thank everybody for watching. Next Episode I’ll pick up where I left off here and address Aristotle’s compositional account of living forms and the ways in which some biological and economic methods have mirrored Aristotle in this second respect. My discussion will elaborate upon the 12th lecture in Daniel Robinson’s series “Great Ideas of Philosophy” if you want to listen ahead.

Be sure to click the subscribe button and if you’d like to comment on the video or read the transcript, please follow the link below to my Steemit page. See you next episode!

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by fingers from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews/crimsonclad, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows and creating a social network. Please find us in the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.