Ep 3: Aristotle's Souls in Biology & Economics

Transcript:

Hello everybody and welcome to the 3rd episode of Paradigms Lost: A Theoretical Synthesis of Philosophical Pragmatism and Praxeological Economics. In this episode, I want to continue my previous discussion of Aristotelean inquiry and its relation to the methods of modern day biology and economics. In particular, I wish to discuss Aristotle’s compositional account of living forms and his understanding of souls. As before, there will be a focus on the ways in which Aristotelean inquiry differs from the more Galilean approach that we are typically taught in science classes. I will also suggest that the methods of biology and economics might actually be closer to the former than they are to the latter - at least in some aspects.

This episode will be an elaboration upon the 12th lecture in Daniel Robinson’s series “Great Idea of Philosophy”. I choose this lecture because of its clear articulation of the differences that Aristotle saw between the non-rational animals that are studied by biologists and the rational animals that can also be studied by economists. So without further adieu, let’s jump into it…

Recall from last episode that, according to Aristotle, all natural things have a formal cause which we today would think of as the structure or form of a thing. In the case of living organisms, however, Aristotle called this form or structure a “soul”.

We must be careful, however, not to misunderstand what he means by “soul” since his use of the term has exactly nothing to do with any religious or mystical connotations. By “soul”, Aristotle simply meant the principle which animates and moves any living thing. For example, he said that if an eye were an organism, then “sight” would be its soul. A soul, then, is basically what we today call a biological system such as an immune system, a reproductive system, a nervous system, and so forth.

As such, a soul is not an entity or substance that can be separated from the material body any more than we can separate a digestive system from all the intestines and stomach within the body. What Aristotle means by “soul”, then, is clearly not a potentially disembodied thing that might survive the death of the material body since a living body just is a soul in the exact same way that a dead body just is a corpse. The soul no more leaves the body at death than the corpse enters that same body at that same moment.

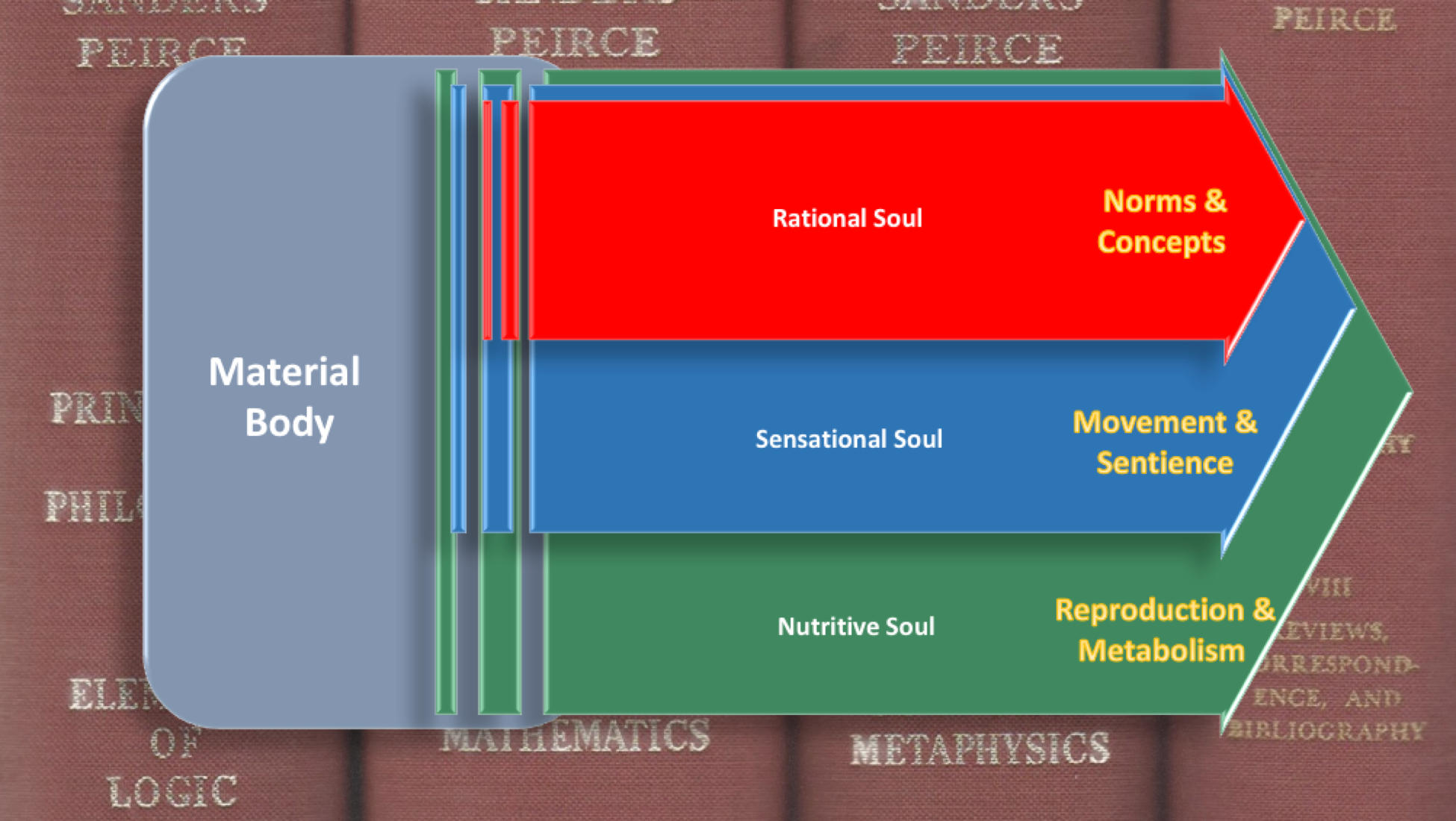

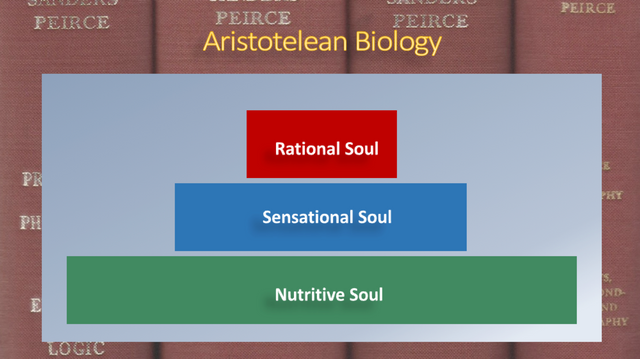

Aristotle thought there were essentially three types of souls and the most fundamental of the three is the nutritive soul that is common to all lifeforms. The teleological end of this soul is what we today call reproduction and metabolism. By saying that all lifeforms have a nutritive soul, Aristotle was simply saying that all lifeforms reproduce and metabolize. Plants, Aristotle continues, are defined as those organisms that have a nutritive soul and no other. As such, nutrition and reproduction are the only potentials that plants are meant to naturally realize.

While all living forms have a nutritive soul, animals also have what Aristotle calls a sensational soul. The teleological end of the sensational soul are those that we today associate with the nervous and muscular systems, namely sense-experience and locomotion. Many of the more developed types of sensational soul even have some capacity for problem-solving. We should not underestimate the level of sentience that Aristotle was willing to attribute to many non-human animals. In fact, he would probably say that the human slaves of his time lived most of their lives according to their sensational souls, leaving the potential of their rational souls largely unrealized.

Finally, some living forms not only have nutritive and sensational souls, but also have rational or a better translation might be epistemological souls. While animals have varying capacities for sentience, humans alone have the capacity for sapience in virtue of our possessing this third and highest type of soul.

The rational soul thus corresponds to the unique access that we humans have to normative and symbolic systems such a language. It is what allows human beings to understand normative concepts such as “right and wrong”, “true and false”, “valid and invalid”. The rational soul is was gives human beings the potential - which few realize - to transcend the self-interested passions of our “lower”, sensational souls in order to acquire the “rational broad-mindedness” necessary for civil service and politics.

This rational soul is precisely what gives humans the capacity for - what philosophers now call - a priori reasoning about the natural world. While the sensational soul is fully capable of accumulating and remembering its experienced interactions with the environment, the rational soul is what allows us to understand our environments in terms of natural laws that hold true beyond the limits of our sense-experience.

As such, Socrates does not have to die before I can learn that he is mortal. Instead, I only need to know that he, like all living forms, has a nutritive soul and by understanding the natural laws associated with that nutritive soul, I can also know that Socrates must be mortal prior to his dying. Aristotle’s taxonomic understanding of a priori reasoning is thus intimately bound up with the asymmetrical dependency that naturally holds between different types of souls and forms.

To reiterate: Aristotle did not think there was anything mystical, supernatural or transcendent about this compositional account of living forms and their souls. In the same way that plants naturally reproduce and fish naturally swim, humans naturally deliberate and reason, and Aristotle simply saw no need for any immaterial realm in which minds and ideas might exist.

I know want to briefly point to the ways in which modern biology and economics both employ modified versions of Aristotle’s hierarchy of souls:

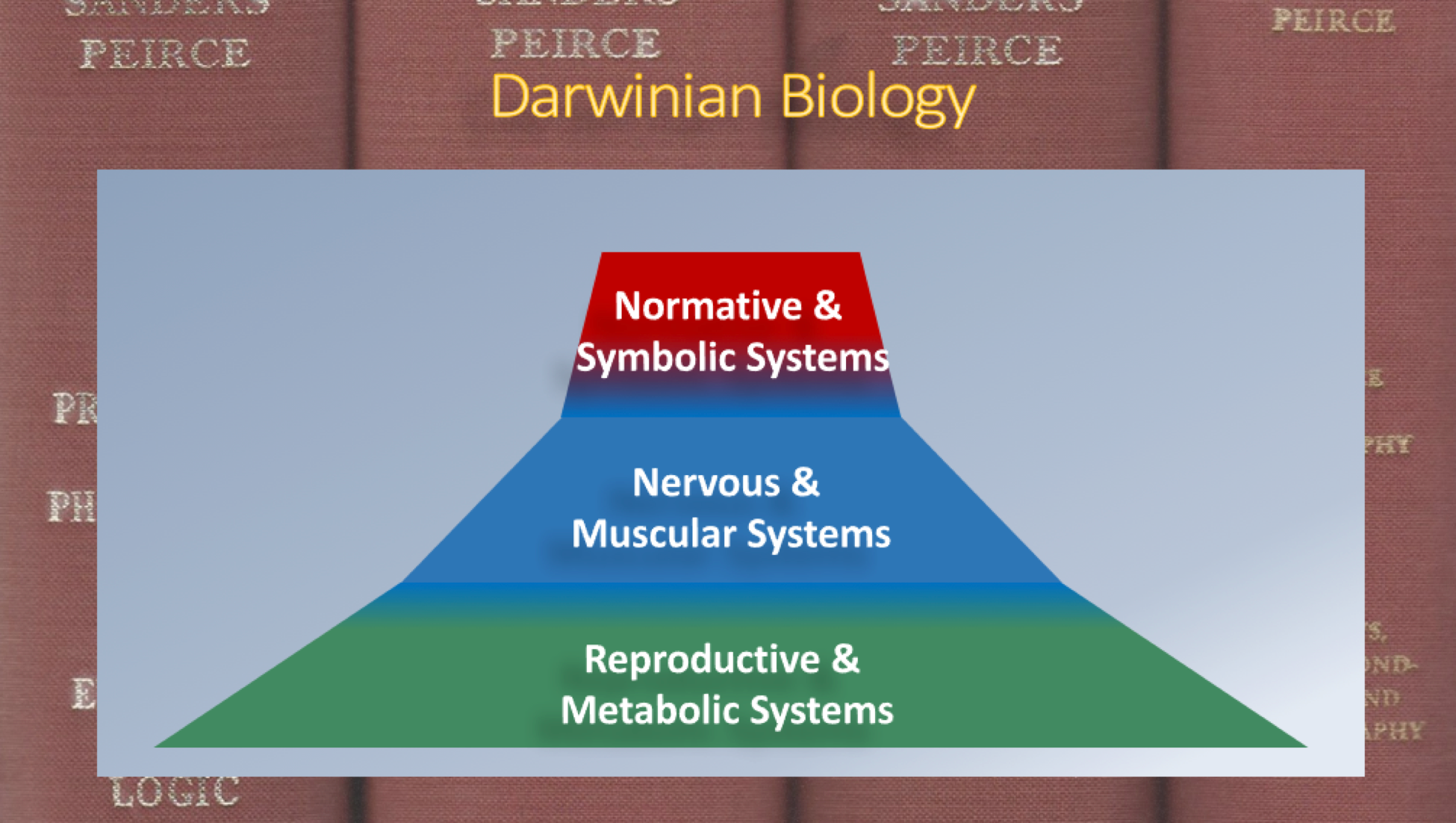

The relationship between Aristotle’s approach and biological anatomy should be fairly obvious. To the extent that biologists think in terms of reproductive systems, nervous systems, and so forth, they are merely carrying forward the Aristotelean torch. Such biological systems closely parallel Aristotle’s souls in being defined first and foremost by the functional role that they play within an organism and only secondarily by the specific mechanisms and organs according to which they carry out their functions.

Of course, modern biology has both deepened and complicated Aristotle’s rather primitive analysis of lifeforms. Aristotle thought there to be 3 basic types of unchanging and categorically different souls. Darwinian reasoning has destroyed all three of these assumptions. The number of biological systems easily numbers more than three, these systems are no longer seen to static over long stretches of time and the presence or absence of a system within a species can no longer be seen as a black and white issues with a yes or no answer.

That said, I think the basic structure of Aristotle’s hierarchical account still hold up pretty well: Biologists would be absolutely shocked to find an organism that clearly had both nervous and muscular systems, but did not just as clearly have reproductive or metabolic systems. They would be similarly shocked to find a fully sapient life-form that had unambiguous access to normative and symbolic systems without also being equipped with nervous and muscular systems. Such bold and categorical predictions far outstretch any set of sense-experience and are rather obvious in their Aristotelean influence.

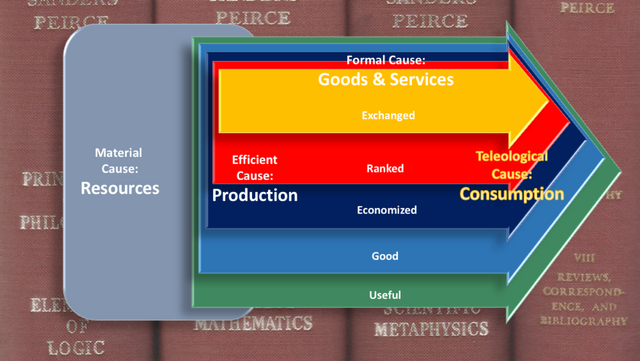

For better or worse, this Aristotelean approach is not quite so explicit within mainstream economics. A notable exception to this, however, is found within the Austrian tradition initiated by Carl Menger. Menger’s contribution to the marginalist revolution was far more Aristotelean in nature than were the more Newtonian approaches of Jevons, Walras and Marshal.

Whereas the latter thinkers had approached marginalism in terms of equating the first-order derivatives of aggregate rates of exchange between various goods, Menger instead provided a qualitative analysis of the nested conditions under which an object is:

• Useful

• Good

• Economized

• Ranked

• Exchanged

Here we again have a hierarchy of conditions such that exchange cannot happen without economization and usefulness first being in place, and so on. This allowed Menger, in his analysis of the higher categories of exchange, to help himself to the assumptions and conditions that characterize the lower categories in an a priori fashion that far exceeded any set of empirical data. To put this method in more Aristotelean terms, in the same way that the rational soul necessarily implies the nutritive soul, so too market exchange necessarily implies the conscious economization of goods on the part of market participants.

Alright, I want to thank everybody for watching. Next Episode I’ll bring my discussion of Aristotle to a temporary stopping point by laying out those aspects of Aristotelean inquiry that I think economics and the social sciences in general should and should not embrace. After that, I will move on to Descartes and his direct assault on these Aristotelean methods.

Be sure to click the subscribe button and if you’d like to comment on the video or read the transcript, please follow the link below to my Steemit page. See you next episode!

Congratulations @paradigms.lost! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @paradigms.lost! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!