The sensory appraisal of objects to judges the quality of taste, art and beauty

Close your eyes and imagine a bronze statue of a cat. But now imagine the statue is placed at the top of a staircase at some big university. Since college students can get up to all kinds of tricks, school officials have placed a chain around the neck of the statue, securing it to its podium, to keep it from being spirited away on some raucous Friday night.The statue, as created by its artist, was unchained. But the chain has been in place for so long, that generations of students have come to know the statue as the “chained cat.” Now here’s the question: is the chain a part of the artwork? Is it a chained statue of a cat? Or has it become a statue of a chained cat?

Maybe you’re one of those people who doesn’t really care about art – even if it is art of cute cats. If that sounds like you, I want to argue that you are just thinking about art too narrowly. Think about your day. If you’re like most people, you devote a lot of your time to aesthetic enjoyment, the pleasure you get from sensory experience and sensory emotion.

Do you listen to music as you drive your car?

Source

Are there posters on your walls,

Source

maybe some stickers on your laptop?

Source

Do you feel your spirits lift when you take in a sunset,

Source

or a colorful bird,

Source

or even an attractive stranger?

Source

Do you savor the first bite of your favorite meal?

Source

Are you emotionally invested in the characters in your favorite shows and books?

Source

All of these experiences are examples of aesthetic appreciation.

Philosophers who ponder how and why aesthetic objects have such a hold on us, and what value they serve in our lives, are known as aestheticians.

And one major question that aestheticians deal with is: what actually is art?

That’s a pretty heavy topic, but one way of tackling it is to start with the objects that we find ourselves admiring aesthetically.

An object of aesthetic recognition is defined as something that prompts valuable aesthetic emotions in us.

As humans, we seem to be drawn to these objects. We choose cars

Source

and phones

Source

and shoes

Source

not solely and sometimes not at all based on function, but also on the basis of beauty. Aestheticians typically divide objects of aesthetic recognition into art objects, which are human-made, and objects of natural beauty.

But as you might expect, there is some dispute about this division, and each category is fraught with intriguing problems. For one thing, where does an art object begin, and end? The frame around a painting, the chain on the cat, the skips in your vinyl recording of The White Album – are those things part of the artwork?

And, does the value of the art come from what’s put into an art object, by the person who created it?

Or does its value depend on the experience that it triggers in the audience?

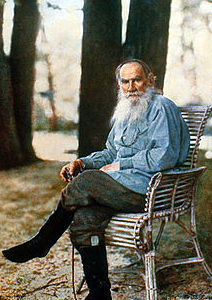

Some people, like 19th century Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy,

Source

understood art primarily in terms of the artist, as an expression of the ineffable emotions of the person who created it. In this view, an artist creates as a way of communicating feelings to other people – oftentimes, feelings that can’t be expressed in mere words. But in some cases, the creation of art might not be about communicating at all – it might just be a way to purge overpowering emotions that are raging inside of the artist.

Some thinkers argue that the intention of the artist is really important – that the artist must want to evoke some valuable emotion in the audience for their work to be considered art. But others think an object can be art even if it wasn’t created with that intent – that art could come about accident! And this possibility raises a lot of questions, too. Because: If an artist’s intention is important in determining what art is, then that rules out the possibility that, say, a natural object could be art, even though it still might be an object of aesthetic recognition.

And in that case, can a non-human animal can create art? Is a finger-painting ape an artist? Iff a skunk walks through paint and leaves footprints on a sheet of paper – has she created art?

Maybe you think that the skunk is not an artist, but that the result of her activities is still art.In any case, not everyone agrees with Tolstoy and his focus on the artist.

Some argue that what makes something art is the aesthetic emotion that it brings out in the audience. So, rather than the point of creation, the real key moment is when the audience encounters, and is affected by, an artwork.

It’s possible that right now you’re realizing that you thought you knew what art was until you started thinking about it. And the more you think, the more impossible it seems to define.

So maybe the answer is to take a Wittgensteinian approach, and argue that the concept of art defies definition, but you know it when you see it. That’ll do, I guess. But it won’t help you decide whether the chain on the cat statue is part of the artwork or not.

To help out here, let’s head over to the Thought Bubble for some Flash Philosophy. Say there’s a row of visually identical paintings hanging on a wall. They’re all square canvases painted the exact same shade of red.

Source

However, each of these paintings has a different backstory. One was designed as a close-up still-life of an empty tablecloth.Another is meant to represent the Red Sea after the Israelites had crossed. Another is a Soviet political statement. There’s also one that wasn’t intended as a finished work of art at all. It was just a canvas that had been primed red in anticipation of being painted, but because it looked like all the others, it was hung up by mistake.

So what’s the difference between these paintings? Can we judge one of them to be a better artwork than another? And if we can, on what basis?

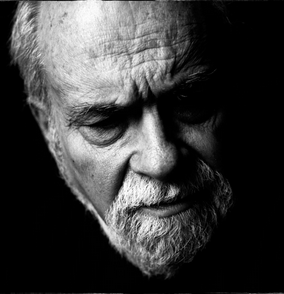

20th century American aesthetician Arthur Danto

Source

the same philosopher who brought us the example of the cat and the chain – presented this thought exercise to prompt us to think about the ontology of artworks.

When you consider works that look identical, but you still manage to recognize differences between them, you’re almost forced to conclude that there’s some non-physical element that makes something worthy of being called “art.”

But what is that thing?

Is it something that exists in the minds of the artists, or the audience, or some historical facts about the works’ creation, that makes the works different?

Aesthetics falls into the broad category of value theory – which also includes ethics. But unlike ethics, where many people think there are absolute right and wrong answers like, killing is wrong, and helping people is good – many people think that beauty is simply in the eye of the beholder. In other words, aesthetic recognition isn’t the kind of thing you can be wrong about – it’s all just a matter of taste.

And this might how you feel about art. But remember, if you really think beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then no one can be wrong about their aesthetic beliefs.And if that’s the case, then we can’t really have a conversation about it, because we’re all the ultimate arbiters of aesthetic goodness.

There are some philosophers who have realized that our intuitions about art tend to be conflicting. Like, on one hand, it all seems subjective, but on the other hand, there have to be some kind of objective criteria. Enter 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume.

Source

He said that when we think about art, we should take care not to confuse the question, “Do I like it?” with the question, “Is it good?” Hume said that, as long as you’re being honest, you can’t be wrong about whether or not you like something. Because that’s totally subjective. But, the question of “Is it good?” is another matter entirely. Hume thought that aesthetic value was objective to some extent, and that we’re all predisposed to find certain objects and patterns to be aesthetically pleasing.

For example, he said that humans are naturally drawn to images of health, but we’re repelled by depictions of decay. And we tend to like symmetry and dislike imbalance. And Hume said that, just as we have a sense of smell and sight and hearing, we also have a sense of aesthetic taste – an ability to detect and evaluate the aesthetic properties of an object. But we may each use our aesthetic tastes in different ways, and be better at appreciating some things more than others. Think about something you know a lot about like a sport, or a musical instrument. Maybe you’re a wine snob. When you encounter that thing – when you go to a game of basketball, or a concert, or try a new cabernet – you’ll notice all sorts of nuances that other people would miss. You recognize small mistakes, and you also appreciate complicated details that others might overlook. Hume said that some people naturally have a refined sense of aesthetic taste, so they might get more out of watching Stephen Curry play, or having a glass of Old Vine Grenache. But, he added, if you don’t happen to have natural “good taste,” it can still be learned over time.

You can study and discover what others appreciate about an aesthetic object that doesn’t currently speak to you. And over time, you’ll recognize it, too, just like you did with basketball, or the bassoon, or the red wines of Washington State – whatever your areas of expertise are.

Now, maybe you don’t agree that some of us are born with so-called “good taste,” or are inherently better at creating, or understanding or appreciating works of art.

But you might share Hume’s view that an ability to appreciate things can be acquired, and that greater aesthetic recognition can be valuable for its own sake, because it gives you pleasure and it lets you understand things about the world, and other people, that you might otherwise miss.

Wow! Incredible article! You really put an incredible amount of work into this and it definitely paid off. Those thought exercises were illuminating. Thank you!

Thanks!