The Crowns of the Pharaohs

In Ancient Egypt, the gods and kings (pharaohs) were depicted with a crown, which, according to Egyptologists, were also taken into the grave for the afterlife. These crowns however have never physically been found, neither inside nor outside graves. Have these crowns really existed or did grave robbers take them all? Not all the graves were looted before archaeologists discovered them and this strengthens the idea that the crowns were only used in depictions and statues to indicate a certain, important phase in the life of a pharaoh.

Therefore, it is not special that no crowns have ever been found, nor any of the artefacts that accompanied the pharaohs like for instance: the crook or the flail and the ankh or the was-sceptre that accompanied the gods.

There used to be different types of crowns like the red crown or Desjret as the symbol of Lower-Egypt, the white crown or Hadjet as the symbol of Upper-Egypt, the double crown or Psjent as a combination of the white and the red crown, the war crown or Chepresj of which is little known, the Atef crown worn by the first mythical king Osiris and the Nemes headdress. Combinations of mentioned crowns were also used. Goddesses and Egyptian queens were often depicted with a hood in the shape of a vulture. A pharaoh in times of war was depicted with the war crown and showed the status in the life of that pharaoh and his kingdom. Therefore a particular crown is linked to a specific era.

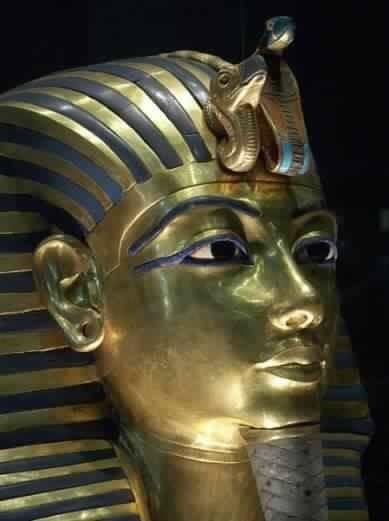

Gods were depicted with crowns because they were the first mythical kings in the time before creation and prior to the first Egyptian dynasty about 5.000 years ago. The pharaohs were the chosen ones and descendants from these gods in Egyptian mythology. Therefore they were provided with a crown to show their divinity. Different crowns represent the life of the pharaoh and the last crown or Nemes headdress marks the conclusion of earthly life and the beginning of life hereafter. The blue-striped Nemes headdress as a death mask. The best example is the death mask of Tut-Ankh-Amen (image 1)

The Nemes headdress or royal blue striped headdress isn't a real crown but a cloth that often covered a crown and the backside of the head. Two parts of the cloth hung downwards alongside the ears on the front side of the shoulders and on the backside the cloth was tied together in a braid and provided with rings. The mythical Uraeuscobra, worn by gods and kings, was often combined with this headdress and symbolised the power and dominion on virtility and prosperity of the land. Only in the case of Tut-Ankh-Amen the Uraeuscobra was depicted in combination with the vulture to symbolise his divinity as the 'feathered serpent'. Just like Quetzalcoatl, the serpent god in Aztec mythology. This makes the young king Tut-Ankh-Amen a very important pharaoh, despite other assertions. He is the only pharaoh depicted with the Nemes headdress provided with both the Uraeuscobra and the vulture.

The Nemes on the death mask of Tut-Ankh-Amen is made of gold and lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli is an azure blue gem, which, in Ancient Egypt, was often laid inside graves to accompany the deceased one in the afterlife. Lapis lazuli was believed to be as a sacred stone with magical powers and was also called heavenly stone because of the connection with life after death. A stone used as an azure 'star map'; the road sign for the soul of the deceased. The Nemes headdress of the death mask shows the combination of gold and lapis lazuli as well as the contrast and agreement between life (gold-sun-life) and death (heavenly stone lapis lazuli). Life embraces death as expressed in the Nemes headdress as a death mask, which functions as a funeral card of the deceased one. A funeral card with the age of the deceased person in solar years. The Nemes as a death mask provides us with this information.

It doesn't matter if the depiction is a statue or a death mask. In both cases it marks the end of the earthly life, either with or without the false beard that decorates so often the depicture of the pharaoh

The ancient Egyptians also used the solar year for the period the sun needed to return to the same point. An Ancient Egyptian year on the calendar begun with the flooding season of the Nile and counted, like in present times, three hundred and sixty five days.

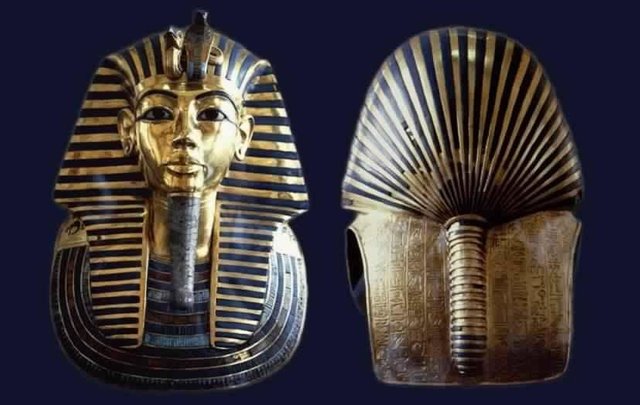

The age of the deceased pharaoh is told through the number of rings (golden life rings) of the braid of the Nemes headdress (image 2). In the case of the death mask of Tut-Ankh-Amen the braid counts nineteen rings and that corresponds to his stay on earth in solar years.

This can also easily be verified with other statues of pharaohs wearing the Nemes headdress with braids divided into rings. In Egyptology it is often not exactly known how old a pharaoh really became.

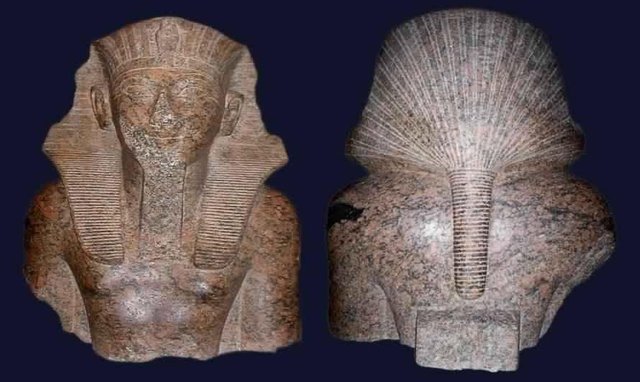

Another example is the granite statue of pharaoh Thutmosis IV, to be found in the Louvre (Paris) of who is said he probably reached the age of thirty-three years. The braid of the Nemes headdress of this pharaoh counts thirty-two rings.

This method may shine a different light on the chronology of Ancient Egypt and the life of the pharaohs and deserves further examination. Unfortunately only few pictures have been taken from the backside of statues or death masks and that shows us that we, in our current society, literally and figuratively are limited in our observation. It is the difference between looking and really seeing.

Just a revelation.

By Willem Witteveen