Trump becomes more dovish toward North Korea, but surrounds himself with hawks

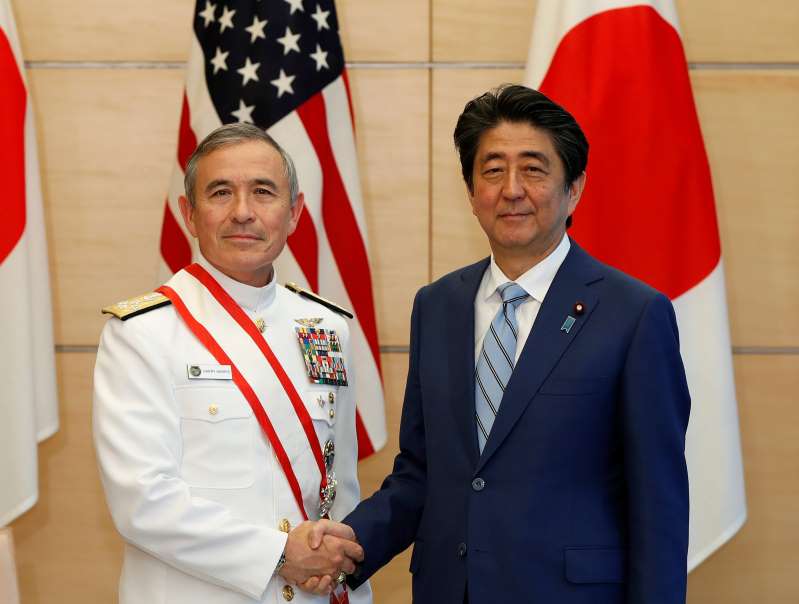

As the top commander of the U.S. military forces in the Pacific, Adm. Harry B. Harris Jr. has been such an outspoken China hawk that he was reportedly subject to a gag order by the Obama administration and targeted with a smear campaign by Chinese state media.

Now, Harris is set to become a key player in the Trump administration’s attempts to craft a diplomatic deal with an even more hostile and threatening East Asia power: North Korea.

Harris is expected to be nominated to fill the long-vacant ambassadorship to South Korea, one of new Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s first decisions last week. The move, just weeks before President Trump is planning to meet with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un, could thrust the 61-year-old Japanese American into the weighty role of translating Trump’s unpredictable strategy to a Korean Peninsula that has been whipsawed between war threats and, more recently, talk of historic peace.

It also reflects an important dynamic in the growing diplomatic thaw between Washington and Pyongyang. Even as Trump softens his rhetoric in hopes of easing tensions with Kim, the president has assembled a team of foreign policy hawks that will be with him at the negotiating table and assume responsibility for hammering out the crucial details if the leaders announce a broad agreement to pursue a nuclear disarmament deal.

Pompeo, who last year expressed a desire for regime change in Pyongyang against long-standing U.S. policy, has taken the lead on coordinating the North Korea summit, meeting with Kim in Pyongyang over Easter weekend. National security adviser John Bolton suggested in March, a month before joining Trump’s staff, that the United States should consider a preemptive strike on the North, noting that the Kim family regime has acted in bad faith in diplomatic talks for 25 years.

And Harris took a hard line during an appearance before the Senate Armed Services Committee on March 15, six days after Trump’s stunning announcement that he was willing to accept Kim’s invitation to meet. Harris, who at the time was not being considered for the post in Seoul, told senators that Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign had successfully brought the North to the negotiating table but added that his view of any nuclear disarmament deal would be to “distrust but verify.” He emphasized that, in his view, Kim wanted the nuclear arsenal as leverage to fulfill the dreams of his father and grandfather to unify the Korean Peninsula under his family’s control.

Asked about military options, Harris responded that, despite media reports, the military was not developing plans for a limited “bloody nose” strike aimed at sending a warning to Pyongyang.

“I believe if we do anything along the kinetic region of the spectrum of conflict, we have to be ready to do the whole thing,” he said, meaning full-fledged military assault against Kim’s million-man army. “And we’re ready to do the whole thing if ordered by the president.”

White House officials did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Foreign policy analysts who know Harris predicted he, Bolton and Pompeo would aim to set guardrails to protect the unpredictable Trump from being hoodwinked by empty promises from Kim. The North Korean leader has suggested he will freeze his nuclear program, but analysts have warned that Kim could easily reverse himself or conduct secret tests once the United States agrees to lift economic sanctions or remove troops from the peninsula.

“You don’t want the president to sign away the alliance,” said Patrick Cronin, an Asia-Pacific security expert at the Center for a New American Security. “With Harry and Bolton and Pompeo, it’s unlikely to be a weak deal. Kim may reject it, but then at least Trump has done everything possible to try to reach a deal.”

It is a high-pressure spot for Harris, who has spent four decades in the Navy since graduating in 1978 from the U.S. Naval Academy and has no background in formal diplomacy. But colleagues and friends said he could be an inspired choice, given his knowledge of the region and ability to navigate incoming political fire.

“Harry is never afraid to be in the center of everything — never afraid,” said Victor Cha, a former high-ranking Asia policy official in the George W. Bush administration. Cha had been Trump’s initial choice for the Seoul posting until the White House abruptly cut him loose in January over a policy disagreement.

“Others might run from fire,” Cha said. “Harry has no problem walking toward the fire.”

Foreign policy analysts speculated that Pompeo, eager to fill the embarrassing opening in Seoul, turned to a well-respected officer with bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. Harris had been in line to become ambassador to Australia before Pompeo yanked his nomination a day before his confirmation hearing to redirect him to Seoul.

In Seoul, Harris’ appointment was met with relief after the top job at the U.S. embassy sat vacant for more than 15 months. Yet his background as a commander could raise eyebrows given that there is already another four-star U.S. commander, Vincent K. Brooks, stationed in the country overseeing nearly 30,000 troops in the United States Forces Korea.

South Korean’s liberal president, Moon Jae-in, has pursued greater diplomatic engagement with the Kim regime, welcoming a delegation from the North to the Olympics in PyeongChang in February and temporarily freezing joint military exercises with the United States.

Harris’s former colleagues said he developed an understanding of diplomacy while serving as the military’s liaison to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

“He’s a stone-killer operator, and simultaneously gets the diplomatic piece,” said James Stavridis, the former Supreme Allied Commander at NATO who is now the dean of The Fletcher School at Tufts University. “When we’re paying him to be a four-star admiral, he’s of course going to be the guy who sounds extremely focused on combat operations and he lives inside those war plans. But everything about Harry Harris tells us he’s able to step outside the military role and inside the diplomat role.”

Mark Lippert, who served as the ambassador to South Korea from 2014 to 2017 under President Barack Obama, said Harris “has the expertise, judgment, and influence at the highest levels in Washington and in the region to be a highly effective ambassador.”

Yet Harris, a varsity fencer at the Naval Academy, is not shy about hand-to-hand combat. In 2016, his intensive criticism of China’s maritime assertiveness in the South China Sea — he derided the construction of artificial islands as a “great wall of sand” — prompted then-National Security Adviser Susan E. Rice to impose a “gag order” ahead of a meeting between Obama and Chinese leader Xi Jinping, according to a report in the Navy Times. Harris called the report “simply not true.”

Beijing responded by launching a smear campaign to discredit Harris, emphasizing his Japanese heritage to suggest he is untrustworthy. Harris was born in Yokosuka to an American father serving as a U.S. Navy chief petty officer and a Japanese mother.

“He still presents in meetings and in public in a manner that comes across at times fairly harsh, but as a military adviser-planner-leader he’s just what the doctor ordered,” said Danny Russel, a former State Department official in the Obama administration who often sat next to Harris on foreign trips with Clinton. “He was the guy in the business of constantly planning for the worst-case scenario. He may feel at times that he needs to showcase the risks to U.S. interests and the legitimate concerns in terms of national security and let the chips fall where they may.”

you have committed a violation please do not repeat again

Such critical time we are in @takibul120