This T-Shirt Sewing Robot Could Radically Shift The Apparel Industry

When the Chinese clothing manufacturer Tianyuan Garments Company opens its newest factory in 2018, it will be in Arkansas, not China, and instead of workers hunched over sewing machines, the factory will be filled with fully autonomous robots and their human supervisors.

Once the system is fully operational, each of the 21 production lines in the factory will be capable of making 1.2 million T-shirts a year, at a total cost of production that can compete in terms of cost with apparel companies that manufacture and ship clothing from the lowest-wage countries in the world. The factory will be one of the first to use a technology that could herald immense changes in how the apparel industry works.

“Our goal is giving a tool for manufacturers to manufacture convenient to their customers,” says Palaniswamy Rajan, CEO of SoftWear Automation, the company that developed the robotic technology that will be used in the new plant.

Sewbot–SoftWear Automation’s clothes-making robot–was developed at Georgia Tech’s Advanced Technology Development Center in a process that began a decade ago. In 2012, researchers got a grant from the Defense Department’s tech innovation wing DARPA to develop the concept and formed a company to commercialize the technology. By 2015, the company was selling a more basic version of the robot that could make bath mats and towels. The newest version, to be deployed in the Little Rock factory, can make T-shirts and partially sew jeans.

Sewing technology in apparel factories, in the most basic respects, has changed relatively little since sewing machines were invented in the 1800s. While others have attempted to automate particular steps of the process of sewing, it’s only now that technology is becoming capable of creating an entire garment autonomously.

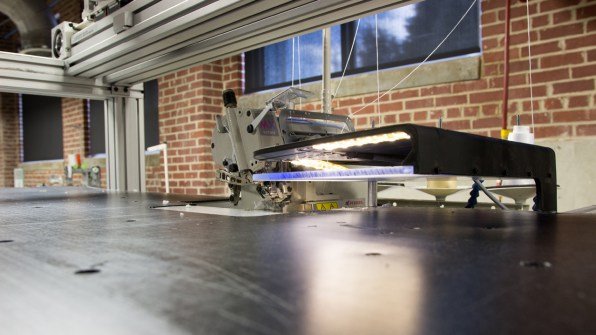

SoftWear’s technology uses computer vision to watch and analyze fabric so the system can move the material while sewing. “What we did was approach it and look at it from how a seamstress actually operates,” says Rajan. “The first thing they do is use their eyes, and based on their eyes, they do micro and macro manipulations of the fabric with their fingers and hands and elbows and feet. So a robot replicates all of those functions.”

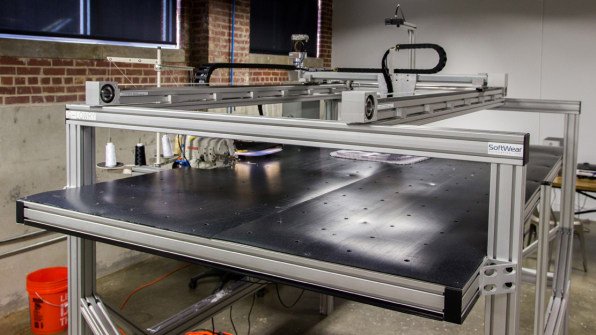

Each T-shirt production line is roughly the length of a typical factory sewing line staffed by humans, or about 70 feet. Along a table, robots perform each step of making a shirt–adding a label, sewing a shoulder seam, adding sleeves, and so on–while the system’s vision technology guides the fabric.

The company is focused first on T-shirts and jeans because the robots’ strength is producing huge quantities of clothing. “People buy 11 billion T-shirts a year,” says Rajan. “That’s an interesting market where automation makes sense, where our robots make sense, because our robots produce a very high volume of product.”

While the technology is still developing, and will eventually make more complicated items of clothing, Rajan believes that some higher-end clothing will always be made by humans. “We’d never do a bridal dress,” he says.

In this respect, he argues that the technology could have a positive impact in countries with large garment manufacturing industries. Workers might shift into doing more artisanal work, at higher wages. If robots make it economical to manufacture more clothing in the U.S. or Europe, where regulations better protect both the environment and labor, low-wage countries might be forced to improve their own performance to compete. “It might create the pressure among them to treat their workers fairly,” Rajan says.

In practice, the transition is likely to be messier. Sewing robots may only threaten certain jobs in developing countries; the machines are expensive (the company won’t disclose the cost) and the company is initially only selling them in the U.S., where manufacturers can save money on the total process because they can avoid factors such as higher industrial electricity bills in some other countries, and can benefit from a “Made in USA” label (the military, for example, is required to buy clothing that’s made in the U.S., while factories that can produce that clothing are dwindling, and the average garment worker is nearing retirement).

They can also have faster turnarounds on orders. For factories in India or China producing cheap T-shirts for a local market, cheap local labor will still make more sense than investing in robots. But some jobs are likely to be displaced. That displacement may grow as others develop similar technology and the cost drops. Another designer is also working on a T-shirt-sewing robot. Amazon filed a patent in April 2017 for “stitch on demand” technology that would sew clothing after an order is placed.

In Bangladesh, where garment workers make far less than what is considered a living wage–often enduring abuse and working in the kind of conditions that led to the 2013 factory collapse that killed more than 1,000 people–the majority of the country’s exports are clothing. More than 4 million people work in the industry. If H&M and Walmart choose to relocate production of some apparel to North America and Europe, people in Bangladesh and other low-wage countries will probably lose jobs, though, in theory, they might also have an opportunity for something better.

“It’s very hard to know how things will play out,” says Sanchita Saxena, executive director of the Institute for South Asian Studies at the University of California-Berkeley. “My guess is that there’s going to be a lot of displacement without any sort of safety net in place, because that’s how these countries work.”

In Little Rock, Arkansas, the new Tianyuan factory will eventually provide 400 jobs. While the robots are fully autonomous, three to five people will be employed to work with each production line; others will work in logistics and other parts of the factory. SoftWear says it has calculated that a robot can create between 50 and 100 jobs downstream, either within factories or in related industries. Some manufacturers may choose to begin buying more local cotton, for example, to use in U.S. factories, increasing farming jobs.

By producing closer to consumers, and by reducing material waste as it sews, the technology can also reduce brands’ carbon footprints. Fashion for Good, an initiative to improve the sustainability of the fashion industry, calculated that the Sewbot can help cut emissions by around 10%, and is supporting SoftWear through a scaling program.

Rajan believes that, on balance, the robot will have a positive impact, both on labor and the environment. (In contrast, one of the first inventors of a sewing machine, in 1832, decided to bury his invention because he was worried about the potential to put seamstresses and tailors out of work.) As another 2.5 billion people are added to the global population, we’ll need more clothes, and apparel is one of the most polluting industries–the robot can help produce those clothes with less pollution. “The efficiencies we can bring are important for humanity’s survival,” Rajan says.