Togo, the dog that saved an Alaskan town from an epidemic

The film "Togo" recounts an act of heroism during the outbreak of a deadly epidemic in an Alaskan town. Actor Willem Dafoe describes what it was like to play the man who starred in it and why "Togo" pays a well-deserved tribute to a canine hero almost a century later.

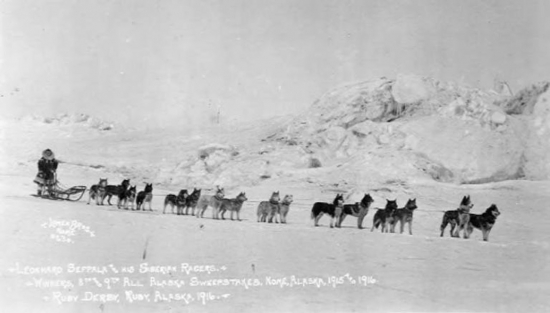

Leonhard Seppala with his sled dogs, ca. 1925. Togo (far left) and Seppala are the protagonists of a new film that narrates the "serum race" of 1925.

PHOTOGRAPH OF CARRIE MCLAIN MUSEUM / ALASKA STOCK

It seems like a story from the Jack London novels. In the dead of winter, a deadly disease afflicts children in an Alaskan gold rush town, isolated between a frozen sea and wild terrain buried under snow. Residents' only hope is an imprecise plan to bring treatment vials from a linehead hundreds of miles across the mountains, across frozen inlets and through a storm. Dog sledding.

But this story is not fiction. The 1925 serum race (as those who know her call it) was an event of such importance that a statue was dedicated to her in New York's Central Park, a space that she shares with 29 other artistic commemorations, such as representations of Christopher Columbus, the characters of Shakespeare and Alice in Wonderland and the John Lennon Memorial Mosaic.

It is a statue of a dog with a stout build and heroic pose that children love to climb on. For those who see it as more than a goal, it is a testament to loyalty, tenacity, and the duty to work for the greater good. The dog's name, carved from the base of the statue, is Balto. I should probably say something else.

The story of a heroism usurped in a way (one that is the very definition of triumph having everything against it) is the basis of Togo, a new original Disney + film that tells a well-known story, but with some unknown names. One is that of the eponymous hound that perhaps deserved to be the one carved in bronze and the one that children climb on; the other is that of its owner, a failed Norwegian immigrant and gold digger-turned-dog breeder named Leonhard Seppala.

(The Walt Disney Company is a majority shareholder of National Geographic Partners.)

The Balto statue in Central Park, New York. Although the plaque dedicates the monument to the "endurance, fidelity, and intelligence" of the serum sled dogs, the canine inspiration is unmistakable. The artist was Frederick Roth and Balto himself attended its inauguration in 1925.

PHOTOGRAPH OF ANTOINE BOUREAU / PHOTONONSTOP / ALAMY

None of the names is known as much as it should, much less for Willem Dafoe, the actor who would end up playing Seppala in which he would be a first step in the world of a man he did not yet know. "I knew the basic story about the serum race," he told National Geographic UK. «The story of Leonhard Seppala and Togo, not so much. Normally, when people know the story, they know Balto. Why?

Isolated and terrified

Nome, high up on the west coast of Alaska in the Bering Sea, is a border town built on the gold and fur trade. It was founded in 1901 and is closer to Siberia than to the state's largest city, Anchorage. Its remote location would present a nightmare situation when, in 1925, an illness began to affect the children of the town. By the time the authorities found out that it was not a serious outbreak of tonsillitis, it was too late: it was diphtheria.

Diphtheria, a contagious bacterial infection that attacks the upper respiratory tract and causes inflammation of the tissues in the throat, can be fatal. So it was in Nome: in late December, two iñupiaq children had succumbed to the disease when it was discovered that the only supplies of antitoxin from the small local hospital had expired. By January 24, four children had died and it was presumed that more had died in the surrounding native Alaskan communities. In a telegram to Anchorage, Nome's doctor Curtis Welch said he had established a quarantine and requested that a million units be shipped to them, claiming that the "diphtheria epidemic is almost inevitable."

Nome in 1916. Nome's population multiplied in 1899, when gold was discovered, and it became a city in 1901, with some 12,500 residents.

CREATIVE COMMONS / WIKIMEDIA PHOTOGRAPHY

Front Street, Nome, in modern times. The city is the goal of the famous Iditarod Race, which was partly inspired by the 1925 serum race. When the gold rush subsided, the population declined and at the time of the diphtheria epidemic had about 1,000 inhabitants, although An estimated 9,000 Alaska Natives lived in at-risk settlements outside the city.

PHOTOGRAPH OF P.A. LAWRENCE, LLC. / ALAMY

The fact that this outbreak was unprecedented was even more terrifying. "In Alaska's history, the 1925 diphtheria outbreak in Nome was one of a series of epidemics in the area and in the rest of Alaska," says David Reamer, historian and writer for The Anchorage Daily News who has written extensively about the diseases of the state's history. “Nome and the surrounding native villages were by far the Alaska communities most affected by the 1918-1919 flu pandemic, the Spanish flu. Hundreds of people died in the region. There were babies who died frozen in the arms of their mothers, who had succumbed to the flu, "he says. "This horror, just seven years earlier, was a vivid memory, and it was undoubtedly on the minds of residents when they saw diphtheria spread among their children."

With some of the worst winter conditions in decades and the lowest temperatures in 20 years, Nome authorities quickly understood that transporting a small supply of antitoxin in Alaska by conventional means would be too slow or impossible before the disease swept the location. The port was frozen and flying was unsafe from the cold, let alone land. With no other way to bridge the massive 1085-kilometer gap between the linehead at Nenana and Nome (a route that messengers used to take a month to travel), they turned to a dog breeder and champion musher named Leonhard Seppala (a musher is the driver of the dog sled).

Seppala's own history spanned many miles. Sepp, a Norwegian immigrant, had traveled to Alaska in search of gold and worked for a mine. Disillusioned by his work, he became superintendent. Their job was to care for the ditches and transport cargo and passengers between dog sledding camps and in a pupmobile designed to run on railroad tracks.

"He is a character from a certain era in history," says Dafoe, whose appearance in Togo as a mysterious-looking Seppala has received public and critical acclaim. "It reminds me of men I have known throughout my life, like my father. People said he was a very pragmatic guy. Not taciturn, just pragmatic. It is that adventurous spirit of getting ahead on your own, of being independent, of learning things. To take care of yourself and not accept charity from anyone ».

Encouraged by his work and charged by default with the training and maintenance of the mine's dogs, Seppala found his vocation. Because he had connections with the entrepreneurial owner of the mine, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen commissioned Seppala to train and groom a team of puppies like sled dogs to try to reach the North Pole from Alaska. Given the prospect of World War I, they canceled the expedition and gave away the dogs that were going to participate in Seppala.

Leonhard Seppala with his "Siberian runners" in 1916.

CREATIVE COMMONS PHOTOGRAPH

Leonhard Seppala with Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen in 1932. Amundsen was the man who beat Robert Falcon Scott in Antarctica in 1911 and for whom Seppala trained a team of dogs for an expedition to the North Pole in 1914. The expedition was canceled. and they gave the dogs to Seppala.

CREATIVE COMMONS PHOTOGRAPH

Sled racing was a natural and collateral activity for anyone working with dogs, be it the Alaskan Malamute, the Husky (derived from esky, short for "Eskimo"), and the Siberian dogs brought to Alaska by the Chukchis in 1908 The propulsive pace of these dogs, their resistance and intelligence made them the perfect engine to cross difficult terrain. The trained dogs for Amundsen were Siberian huskies, so Sepp (who now had his own team) began competing in Alaskan races. Beginning in 1915, Seppala had three consecutive victories in the All Alaska Sweepstakes, a 656-kilometer unhindered race from Nome to Candle that followed the route of the telegraph line. Seppala's victories were credited to his light-built dogs, which other mushers called "Siberian rats." That and the instincts of the leading dog, a position that Seppala would soon assign to a particular dog.

Togo's history

Named after the heroic Japanese admiral Heihachiro Togo, Togo was born in 1913. His future in dog racing didn't look very promising at first. He had a mottled color that gave his hair a grubby appearance and was raised by Seppala's wife Constance when she was a puppy due to a sore throat, a circumstance that could account for her smaller build, willing temperament, and ingrained loyalty. to his owner. Togo often escaped to run after Seppala when training or running errands. As he considered it a nuisance, after seven months he gave it to a friend as a pet, but Togo fled and returned home. At this point, Seppala noticed an indirect virtue of the dog: his determination and his ability to find the shortest distance between two points.

Norwegian Leonhard Seppala left the search for gold to dedicate himself to the training and breeding of sled dogs. In Togo, he is played by Willem Dafoe, an American actor nominated for an Oscar.

ALAMY / DISNEY PHOTOGRAPHY

Dafoe, whose interpretation of the mysterious Seppala in Togo has received wide acclaim, believes the Norwegian saw something of himself in the dog. Seppala was quite determined. He was of small constitution, was an immigrant and had had some disappointments in his life, "he says. “So, in a way, that was analogous to his projections in Togo, which was kind of doomed to failure. He was too small, he was modest, he was undisciplined and he was basically branded as failure. Maybe he identified with it.

Although perhaps he was a bad gold digger, Seppala ended up finding his own niche. "I think it is always very helpful to play a character who has a very central action, or experience, or passion, or profession," says Dafoe. "I always feel that the way to get into the characters is to know how they do what they do or adapt to their way of thinking in the most practical way possible."

For Togo, that meant taking the reins and physically learning Seppala's chosen profession. "You think it seems easy ... it's a guy sitting in the back and the dogs are the only ones that pull," he jokes. But it's not that simple. You have to meet the dogs, hone the tension of the rope, face the discomfort, the cold, keep your balance, read the terrain; are a lot of things. It takes a very tough character.

Royal Togo (left) Remains in the lineage of the Siberian Seppala, whose owners often trace them back to their heroic ancestor. One of them is the dog that appears in the film, Diesel (right), a Siberian husky who is a direct descendant of Togo.

CREATIVE COMMONS / DISNEY PHOTOGRAPH

Fed up with the constant escapes from Togo, Seppala ran into him with the team, first behind, then later and finally in the lead, where the dog really shone. In The Cruelest Miles of Gay and Laney Salisbury, Seppala is quoted as saying that in Togo "declared a born leader ... something he had tried to raise for years." The two would become inseparable and, in the coming years, on their many expeditions, they would save the other's life.

The "great race of mercy"

When the diphtheria outbreak came, Seppala was already a famous musher all over Alaska (they called him "king of the trail") and his cunning and tiny Togo was equally revered as a guide dog. On the night of January 14, 1925, the authorities of Nome called Seppala to head the one that would become known, in the hyperbole of the many subsequent headlines, the "great race of mercy." As the round trip for the nearly 2,100 kilometers separating Nome from Nenana was impossible for a single team, diphtheria antitoxin vials (the only 300,000 units in Alaska) transported by sled dog teams from Nenana to Nome to through a media scale in Nulato. In this way, each journey would be just over 1000 kilometers.

The dangers were considerable. Seppala would handle the treacherous sections of the interception stage from Nome and be forced to get around the Norton Sound coastline, a strait that bore the chilling nickname "The Ice Factory." The most dangerous part of the trip would be shortcut through the frozen strait, a shortcut that would save you a day, but which was riddled with high winds and unstable and sharp ice floes. It was a stage that many (including Seppala) knew that only he could manage with Togo's instincts to read the danger and the terrain. But even this would be a difficult task: At that time, Togo was already 12 years old.

Seppala left on January 27. As the outbreak and weather conditions worsened, Seppala would move on without knowing that the already improbable plans had been changed on the way. Thus, they were at considerable risk of skipping an encounter in the rustic cabins or "paradores," the only respite along the route. As the Nome outbreak worsened, more mushers and kits were added to relieve pressure and speed up the transit of the medication, ampoules wrapped in hair and sealed in a metal container.

The relay from Nenana advanced faster than expected. By sheer luck, Seppala intercepted the serum of a musher named Henry Ivanoff outside Shahtoolik and returned to Nome in worse condition.

"It takes a very tough character." Willem Dafoe as Leonhard Seppala in Togo.

PHOTOGRAPH OF DISNEY ENTERPRISES LTD

In the region, temperatures were -35 degrees with thermal sensations of -65. Seppala relied on Togo's instincts when he couldn't see the way due to the foam, headwind, and deep snow. Due to his exhaustion and that of his dogs, Seppala was forced to stop at Golovin with 125 kilometers to reach Nome. Since the start, the team had traveled a total of 420 kilometers and crossed Norton Sound twice on treacherous ice. Later, a musher named Charlie Olsen transported the antitoxin about 50 kilometers from Nome, where Gunner Kaasen was waiting with a team of 13 dogs led by Balto.

Balto's resulting fame, alongside that of Musher Kaasen, was an unfortunate but unintended consequence.

The 1085-kilometer journey of the antitoxin took five and a half days, a world record witnessed by a public on embers. It was accentuated by the recent adoption of radio by the American middle class, which turned the history of the serum race into a phenomenon broadcast remotely. In Nome, five to seven people died, although the death toll among native Alaskans outside the town was not recorded and is likely to be much higher. Still, it was clear that further loss of life had been miraculously prevented. The story became a sensation, and also its heroes.

Balto was the dog that led the final stage to Nome and allowed Kaasen to deliver the antitoxin on February 2. A simple glance at the mileage would have contextualized that erroneous credit: Balto and Fox, with Kaasen, covered 80, 85 or 88 kilometers (sources vary), while Seppala, with Togo, transported the serum along 146 kilometers through terrain much more technical and dangerous. In total, Togo traveled 420 kilometers door to door; Balto, just over 160.

Gunnar Kaasen with Balto, the guide dog of the last stage of 80 kilometers to bring diphtheria antitoxin to Nome in 1925. As they were the final messengers who transported the serum, both became famous.

BROWN BROTHERS / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS PHOTOGRAPHY

Balto would inspire a statue, several books, a dramatized documentary, and a cartoon movie.

ALAMY PHOTOGRAPHY

But the public wanted a hero and they chose Kaasen and Balto, the faces of Nome's salvation. Their photos appeared on the front pages of the newspapers and their names would go down in history, eclipsing not only Togo and Seppala, but the other 18 people and about 150 dogs that participated in the relay. "Generally speaking, Balto's fame hides the other mushers, including many Alaskan natives whose contributions were much more forgotten."

A deserved recognition

Kaasen and Balto's stage was also heroic: although they did not do so many kilometers, the conditions were so bad that Kaasen, who circulated at night, hardly saw the dogs. During the ride, the sled overturned and he had to look for the antitoxin package in the snow with his bare hands, which caused him to suffer frostbite injuries.

All in all, the competitive Seppala was not very happy with the flattery Balto received. Although he was the owner, breeder and handler of the dog that Kaasen had used in his team, Seppala maintained that Balto was a "second-rate dog" compared to his beloved Togo and that Balto had co-led with a dog named Fox for those last few kilometers. . The New York Times added to the confusion in 1927, when it reported that Balto was not the true hero of the serum race, but Fox. The rest of the brief story, which did not mention Togo, was devoted to Balto's alleged whereabouts.

The latter had suffered a cruel twist of fate. After the serum race, in addition to the Central Park statue, Balto was awarded the (bone-shaped) key to the city of Los Angeles, acted in a movie, and toured the contiguous United States in front of an admiring audience. But when Kaasen got fed up and wanted to return to Alaska, Balto and his fellow dogs were sold (no one knows by whom) to a vaudeville side show. There he suffered abuse until a fundraiser got him admitted to the Cleveland Zoo, where he lived until the end of his days.

Although small, the 2001 Togo statue in Seward Park, New York, gives the dog a presence in the same city where Balto's much larger statue is.

PHOTOGRAPH OF DISNEY, INC

Truth vs. legend

As Balto's name has already enjoyed fame, books, statues, and even a cartoon movie (dubbed in original by Kevin Bacon and in Spanish by Juan Antonio Bernal), Alaskan historian David Reamer is pleased to see that the new movie will clarify the matter. "The film manages to correct a historical injustice without getting bogged down in minutiae," he says. "The story doesn't need any more drama, that's for sure."

The serum race also inspired the world's most famous sled dog race - Iditarod, which runs a similar route between Nome and Nenana before continuing south to Anchorage. Togo's lineage continues in the Siberian Seppala and the 107-year-old dog "lives" at the Iditarod headquarters in Wasilla, exposed in a glass case (Seppala mounted his hair after his death). The dog and the race date back to a time in Alaska history when the sled dog was vital to human survival in wild terrain.

Aunque es pequeña, la estatua de Togo de 2001 en Seward Park, Nueva York, aporta al perro una presencia en la misma ciudad donde es´ta la estatua mucho más grande de Balto.

FOTOGRAFÍA DE DISNEY, INC

Verdad vs. leyenda

Como el nombre de Balto ya ha disfrutado de la fama, los libros, las estatuas y hasta una película de dibujos animados (doblado en versión original por Kevin Bacon y en castellano por Juan Antonio Bernal), al historiador alaskeño David Reamer le complace ver que la nueva película aclarará el asunto. «La película logra corregir una injusticia histórica sin empantanarse en minucias», afirma. «La historia no necesita más drama, eso seguro».

La carrera del suero también inspiró la carrera de perros de trineo más famosa del mundo: Iditarod, que recorre una ruta similar entre Nome y Nenana antes de seguir al sur hasta Anchorage. El linaje de Togo continúa en los Seppala siberianos y el can de 107 años «vive» en la sede de Iditarod en Wasilla, expuesto en una vitrina (Seppala montó su pelo tras su muerte). El perro y la carrera se remontan a una época de la historia de Alaska en la que el perro de trineo era vital para la supervivencia de los humanos en un terreno salvaje.

"Alaskan literature is full of stories about dogs being born leaders like Togo ... with an almost amazing ability to assess obstacles," Gay and Laney Salisbury wrote in The Cruellest Miles. "Without those dogs, many Alaskans believe that Alaska could not have developed."

Likewise, the race itself had another legacy: it saved thousands or even hundreds of thousands of lives from the subsequent generation. "At a time when supplying much-needed antitoxin was not feasible by air or by sea (coupled with determination and tenacity to save the children of Nome), the story of the dog sledding relay fueled the need and the importance of vaccination, ”says Dr Basil Aboul Enein of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. "It is a story that still echoes in the annals of the history of public health."

"It is a story that still reverberates in the annals of the history of public health." A scene from Togo.

PHOTOGRAPH OF CHRIS LARGE / DISNEY ENTERPRISES

The problem of the Balto statue in Central Park also continues to echo. In late 2019, a petition was created on Change.org to replace the statue of Balto with that of Togo. In New York's Seward Park, there is a small Togo statue that opened in 2001 and was recently moved to a more prominent location during the park's renovation (Seward is the surname of the Secretary of State who bought Alaska from Russia in 1868).

Regarding the film, Willem Dafoe is sure that the story of Seppala and Togo goes beyond correcting the usurpation of a dog's fame. “It is going to have different meanings for different people, like everything. I suppose the main thing is to open up to the place where you fit in the world, "he says. "The interdependence between us and nature, us and the animals ... so that it leads to a better way of life and to better understand why we are here."

"Everyone wants to be useful. I think this was his moment, he felt it was something he had to try. I don't think I had any choice.

Togo is now available on Disney +.

Thanks for stopping by my post, I hope you have a good day. Regards