Nam June Paik: Seeing the Buddha in TV Buddha

Dear Steemit friends,

After enjoying a great day in Breda with @chhayll and @chhaylin among others, I have decided that I would like to share my artistic and academic work on Steemit to give my friends and the Steemit community an idea about the things I make and the things I think about :)

In the next few days, I am going to post work on Steemit that has been produced in a school context (I study a Bachelor in Fine Arts course at Sint Lucas School of Arts and Design in Antwerp) so mind you, these works would normally not see the light of day outside of this academic context. I have always found the hermetic art scene horrible and had always imagined art should and would move dynamically in spaces beyond the art scene, so that the works become even more multidimensional and more importantly exposed to those (like myself) for whom the artistic environment is not a given.

Yet hypocritically, I did the exact same thing the last two years of art school - keep the work embedded in the tiny arts scene in Antwerp. It is horrible, because I speak highly of not dumbing down content under no condition and not underestimating audience(s) yet I catch myself being judgy and thinking: will people understand the rich context in which my academic and artistic work has been crafted on a place like Steemit? And I can answer that question very easily, now: yes.

So, you can expect some work produced by myself in the next coming posts!

Today, I will start with an essay, which is not something traditionally related to art school nor do I see it as an artwork. I study Fine Arts in Belgium and I am under the impression that the Belgian school system values an outdated kind of academia, such as forcing the students at 'attempting' to write academically. I don't agree with it at all: I feel that the school does not have the right support system to want to claim such works from their students, nor do I feel that it is neccesary as an artist to understand academic writing. Nevertheless, I do enjoy writing and out of pure enjoyment I wanted to share this essay with you.

I wrote this essay last semester for my course on Art History for dr. Sofie Verdoodt (Sint Lucas Antwerpen). We were free to choose a topic of our liking under a few themes. My theme was on Arts and Religion. I focused on the oeuvre of the Korean-American video artist Nam June Paik, whom I greatly admire(d) and I was always under the impression that he worked in a very Orientalist context, which is what I wanted to explore. In this essay, I do a modest attempt of sketching this Orientalist context and give a morphological analysis of one of his famous works called "TV Buddha".

Please excuse me as I have treated Buddhism very lightly in this essay and I don't necessarily 'argue' in this essay. At this particular school no single lesson focused on arguing in an essay - which is horrible for essaywriting in my opinion - and there's more or less a focus on 'seeing it your own way and writing about it', which I kind of tried here... Anyway, read away!

PS: apart from the image below I have added more images to the essay to enrichen the text, which were not included in the original essay.

Seeing the Buddha in TV Buddha

A year ago, when I was reading about Nam June Paik’s artistic career and carefully studied TV Buddha in my textbook a few questions popped up in my head: How do works like TV Buddha situate in the context of an Asian artist working in the West, particularly at a time when Zen Buddhism became popular among post-war American artists? As a self proclaimed non-Buddhist does he solely refer to Buddha as an icon in Western or Asian context, or is there no difference? Did he see it in a religious (Buddhist) or a cultural (Asian) sense? Does the context of the Zen-inspired Fluxus movement and his relationship with John Cage influence how critics see Paik’s work? The question I therefore seek to explore in this essay is: Are Nam June Paik’s works, especially TV Buddha, about (Zen) Buddhism?

Many critics believe so, especially in the case of TV Buddha. The following is an excerpt of an analysis by Edith Decker (Smith, 2000) which is representative of most of the commentary: “The Buddha, who wishes to keep himself free of all external impressions in mystic contemplation, now sits confronted by his own image. . . . In zazen, (which is) concentrated, motionless sitting in front of a wall, the intention is to suppress the ego to enable unity with cosmic energy, but TV Buddha represents a superficialization of this principle of self-confrontation. The artist’s Buddhist origins show on a number of levels in this work; rooted in the Zen tradition he formulates a visual koan.”

I want to challenge these Zen interpretations by firstly creating a broad and associative overview of ideas and arguments surrounding these analyses and secondly by creating an analysis of my own.

.jpg)

Challenging Zen analyses through themes and ideas

Whether Paik’s work is about Zen Buddhism or not, his work is often discussed from a Western perspective. Smith (2000) opts for an intercultural perspective. According to him, Paik is the embodiment of interculturalism, having been born in Korea, educated in Japan and Germany and worked most of his life in the United States. Smith states that intercultural artists use and borrow imagery and motifs from the different cultures they work and live in, and that critics often are vague and cryptic when they address Asian imagery in Paik’s art. This could indicate a serious flaw in critic’s analyses and interpretations which in turn could had ripple effects on analyses that have followed. Some hints of Orientalist ideas are evident in commentaries surrounding Paik and in my eyes illustrate this idea of Eastern ignorance. He was often seen as John Cage’s Zen monk, even though he said he was not a Buddhist (Mellencamp, 1992), and his declaration “Yellow Peril! C’est moi” (1963) reads as an ironic comment of his racial position in the West at the time.

Perhaps the well-known friendship between Paik and John Cage and the affiliation with Fluxus inspired the Zen analyses. John Cage was a well known Western patron of Zen Buddhism and the influence of John Cage and the existence of their friendship and mentorship is well documented. Many descriptions of quotes and passages in numerous texts exhibit the life changing moment of Paik meeting Cage. Dramatic quotes of Paik such as “My life began one evening in August 1958 in Darmstadt. 1957 was 1 BC (Before Cage). 1947 was the year 10 BC” (Daniels and Inke, 2012) and “[M]y past 14 years is nothing but an extension of one memorable evening at Darmstadt ‘58” (Larson, 2012: 389) are not rare. Both quotes refer to Cage’s lecture on Zen Buddhism in Darmstadt Paik attended. Paik claims Cage was his sole reason to move to the United States (Ha, 2015) and he has made many hommages to Cage, e.g. Hommage à John Cage (1959), the score Gala Music for John Cage’s 50th Birthday (1962), the videotape A tribute to John Cage (1973) featuring Cage himself, the sound piece Empty Telephones (1987), the 1990 video sculpture Cage from Family of Robots, Cage in Cage

(1993) and the drawing Cage Waves (1996) (Tanasoaica, 2013).

A tribute to John Cage, Nam June Paik, 1973-1976

Despite Paik’s exhibiting love for Cage, this does not mean he automatically agreed how Cage interpret Zen. Larson (2013: 401-402) writes that according to Cage, Paik seemed to have no interest in “Suzuki’s diagram on ego” and his defined discipline in his life and path, citing this to be one of the irreconcilable differences between Paik and him. Even though Paik was initially sceptical of Cage Zen but changed his mind after the Darmstadt lecture (Tomkins, 1975), there is no evidence Cage activated Paik to become a (Zen) Buddhist or to create Buddhist art. Some scholars state that Cage merely used Zen as a strategy to create a new experimental form of music (Low, 2007) and that he disregarded Zen’s social and historical context and wasn’t concerned with ritual practices (Monroe, 2013), which Paik might have deeply understood.

Paik was rarely explicit about Zen Buddhism, only in the June 1964 edition of cc fiVe ThReE he wrote extensively about Zen: “Now let me talk about Zen, although I avoid it usually, not to become the salesman of "OUR" culture like Daisetsu Suzuki, because the cultural patriotism is more harmful than the political patriotism, because the former is the disguised one, and especially the self-propaganda of Zen (the doctrine of self-abandonment) must be the stupid suicide of Zen…. Zen is anti-avant-garde, anti-frontier spirit, anti-Kennedy. Zen is responsible of asian poverty. How can I justify ZEN, without justifying asian poverty ??” (Doris, 1993). On the question if he were a Buddhist, he replies: “No, I’m an artist…. I’m not a follower of Zen but I react to Zen the same way as I react to Johann Sebastian Bach” (Mellencamp, 1992).

It is not unusual for artists to deny particular interpretations of his or her work or to distance him or herself from specific themes. In the case of Paik, critic Herzogenrath states that he is silent on the subject of symbolism and that he likes, in the tradition of Fluxus, multiple analyses and interpretations, as for him the acquisition of a work of art by the viewer is a component of the work (Munroe, 2009). It echoes the philosophy of Duchamp, one of Paik’s mentors, where the artist is a mediumistic being who does not really know what he is doing or why he is doing it. It is the spectator who deciphers and interprets the work’s inner qualifications, relates them to the external world, and thus completes the creative cycle.

It begs the question whether Paik’s intention in his work actually matter and how much of his own ideals can alter the symbolism the works express. If he is so anti-Zen, why has he created so many Buddhist related titles, such as Zen for Film, Zen for TV, TV Buddha, Zen for the Head and his ‘63 Wuppertal performances Zen for Hand, Zen for Face, Zen for Walking, Zen for Wind, Old Zen? Should we believe Paik when he said he came up with the title Zen for Film solely as an artistic coincidence (Hölling, 2017) and not as a conscious choice?

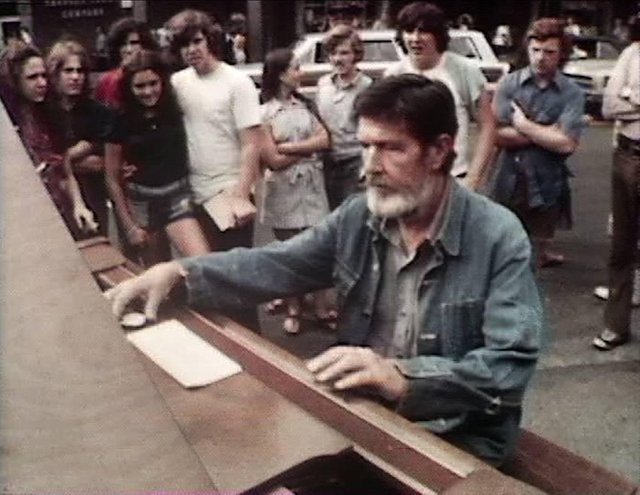

Zen for Head, Nam June Paik, 1962

He has mentioned some Buddhist notions in explaining some of his works (karma, samsara or nirvana). For instance, when explaining cybernated art, he says philosophically: “Cybernetics, the science of pure relations, or relationship itself, has its origin in karma.... The Buddhists also say: Karma is samsara. Relationship is metempsychosis” (Shanken, 2002). In his rhetoric as an advocate of video, Paik proposed that: “[p]eople can create their own art and send it to their friends through video-telephone lines and elevate their mood by watching or attaching certain medical electronic gadgets and control their own brainwaves in order to achieve an instant Nirvana” (Munroe, 2009). The most obvious of all referrals I find was when Paik for opening night of his installation work TV Buddha in 1974, sat on a platform in a lotus position looking at his own live frontal image on a video monitor and became, in his words, a “LIVING BUDDHA” (Winther-Tamaki, 2011).

Analysis

In the spirit of Fluxus’ where all interpretations prevail I will to attempt to analyse TV Buddha myself (see appendix, 1.1) and end with a personal conclusion of both this essay and my analysis.

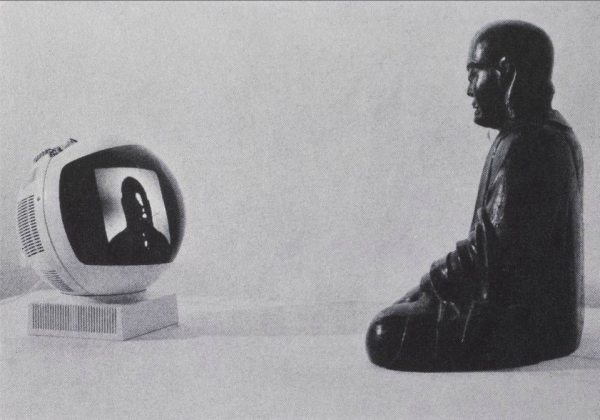

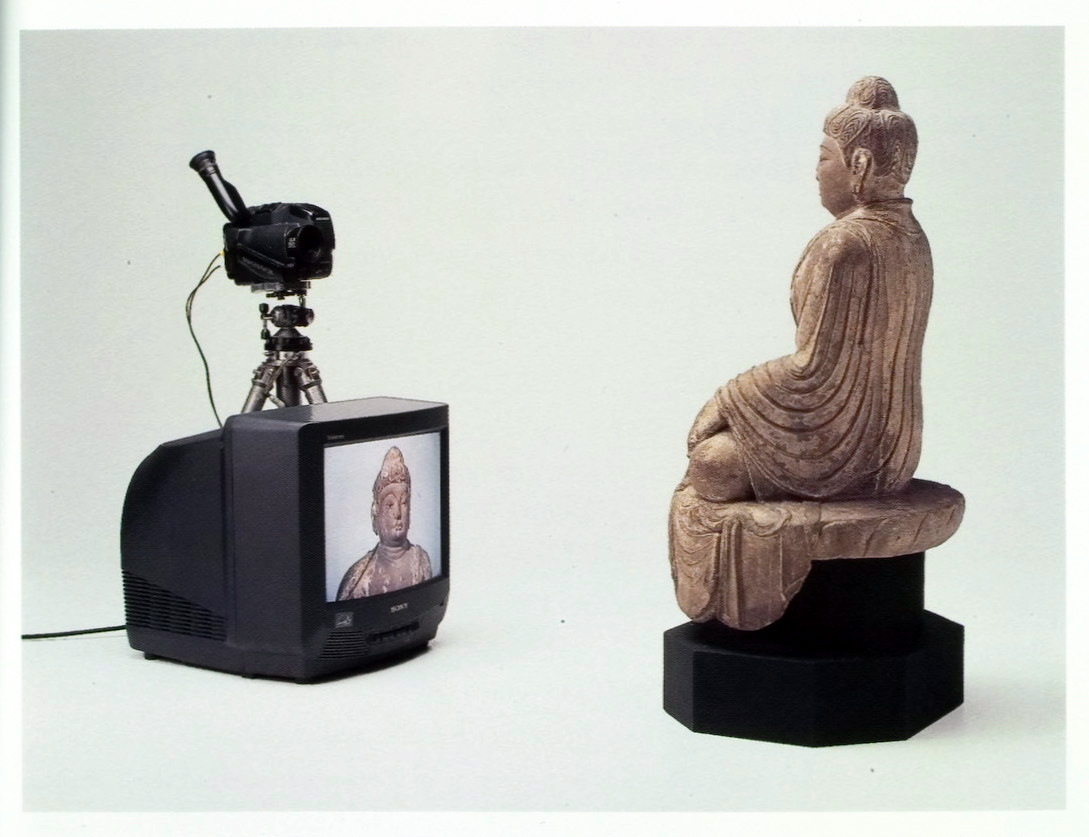

The work we are looking at is a spatial installation consisting of 4 objects, including the pedestal. The pedestal is a white cuboid, and on one end there’s an object that looks like a statue of a sitting Buddha painted in black. On the opposite side is a generally white spherical shaped object on its own small pedestal. The rectangular blue image of the object suggests a screen, and the object altogether of a television or monitor. The monitor’s aesthetic has futuristic connotations, as technological objects that are white and round are associated in popular culture with spaceflight. Behind the pedestal is an object consisting of a pole and a cuboid with a sphere reminding us of a glass or lens. The object altogether looks like a video camera. The aesthetics of this video camera is of a closed circuit television camera, which is often used in the public space for monitoring. The CCTV lens is directed at the Buddha statue. We are under the impression that the projection on the screen is what the CCTV captures: the Buddha statue.

The CCTV camera with wires and the round monitor are symbols for surveillance and human technology. They are associated with ideas of real time, monitoring, the government, cliched ideas of the future, Orwellian society and being interconnected. The Buddha statue is associated with religion and spirituality. Ideas include karma, nirvana, meditation and enlightenment. The Buddha statue also has worship, temple and monk associations. The Buddha statue is faced towards the monitor and its appearance is being broadcasted.

If the Buddha were to be a real person, it would be looking, and in this position, it would be looking at itself. It’s a playful thought to, as a grown person, imagine that the Buddha has eyes and a conscious and is actually looking at itself or even watching “TV”. Even animists who carry beliefs that non-living objects house spirits do not literally phantom that a Buddha statue is ‘alive’ with eyes and arms - but children do with their toys. I feel it is ironic and witty. Even though there is a juxtaposition in material between the Buddha and the monitor, CCTV (being wood and plastic), they are both manmade and made with a particular precise level of execution. They both are made to appeal to human’s experience of imagining or seeing parallel worlds. As they face each other, they seem to compete, but as the Buddha is mirrored, the competition fades and they merge.

What I read is an ironic and playful way of juxtaposing two objects that house a different kind of spirituality in such a way that they speak to each other. I am aware that other critics have written about this works in terms of Eastern tradition and Western technology (Sohet, 1986 in Smith, 2000), Duchamp type irony (Hanhardt, 1982 in Smith, 2000), of course Zen (Mellencamp, 1995 in Smith, 2000; Decker, 1993 in Smith, 2000) and perhaps my analysis is flat and shortsighted. But in the spirit of Fluxus that everyone’s interpretation matters and not just Paik’s opinion or Western critics: as a non practicing Buddhist of Khmer origins heavily influenced by folklore and Khmer animism I feel like this work speaks to me as a friendly wink or nudge to my own work. This year I created a work with a beamer projection and smoke machine, where dancing hands inspired by the Apsara dance gestures are projected in a bric a brac hologram way and in retrospect I feel I wanted to express my kind of ridiculous belief of animism in 21st century. Perhaps it’s the same thought Paik wanted to express: the complex system of human beings and our vulnerable spirituality, the advancement in technology, the potential and danger of moving forward and the inevitability of this continuing imbalance between spirituality and technology.

Conclusion

What Paik’s intention was and how we should read his work is almost completely overruled by the Fluxus’ tradition he tried to uphold: that multiple interpretations become part of the work and his intentions does not matter. Nevertheless it is interesting to try and understand the context in which Zen inspired analyses were created and how they juxtapose the few words Paik has uttered about Zen: Paik has written an anti-Zen statement where he blames Zen for Asian poverty and claimed he was not a Buddhist. Yet to give credit to the his Zen inspired critics: many of his works have Zen references, for instance in titles, and he has not shied away from using Buddhist concepts in explaining his works. It is important to note that there is a chance his critic’s were influenced by his well known relationship with John Cage or by Orientalist ideas through lack of interculturalist understanding. In my own analysis of one of his most ‘Eastern’ work TV Buddha I have concluded that this particular work is not about Zen Buddhism but about the precair condition of mankind’s spirituality in times of technological advancement.

References

Daniels, D & Inke, A. (eds.) (2012). Sounds Like Silence. John Cage - 4'33" - Silence Today. Leipzig: Spektor Books

Doris, D.T. (1993). Zen Vaudeville: A Medi(t)ation in the Margins of Fluxus. New York, New York: Department of Art History, Hunter College

Ha, B. (2015). A Pioneer of Interactive Art: Nam June Paik as Musique Concrète Composing Researcher. In ISEA Vancouver, International Symposium on Electronic Art

Hölling, H. B. (2017). Paik's Virtual Archive: Time, Change, and Materiality in Media Art. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

Larson, K. (2012). Where the heart beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the inner life of artists. New York: Penguin Books

Mellenkarnp, P. (1995) The Old and the New: Nam June Paik. Art Journal 54, 4, p. 44.

Munroe, A. (2009) Buddhism and the Neo-Avant-Garde: Cage Zen, Beat Zen, and Zen. In A. Munroe, (ed.), The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989,(pp. 199–215). New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications Shanken, E.A. (2002). Cybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in the 1960s. In B. Clarke & L.D. Henderson (Eds.) From Energy to Information: Representation in Science, Technology, Art, and Literature. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press

Smith, W. (2000) Nam June Paik's TV Buddha as Buddhist Art._ Religion & the Arts_, 4.3, 359-73.

Low, S. C. (2007). Religion and the Invention(s) of John Cage. Syracuse: Syracuse University

Tanasoaica, L. (2013) Nam June Paik: Escaping Cage . Retrieved May 8, 2017, from https://medium.com/history-of-art/nam-june-paik-escaping-the-cage-d5f6fdfdd750

Tomkins, C. (1975, May 5) Profiles: Video Visionary, Nam June Paik. The New Yorker. p. 47.

Winther-Tamaki, B. (2011). The ‘Oriental Guru’ in the Modern Artist: Asian Spiritual and Performative Aspects of Postwar American Art. In S. Inaga (ed.) Questioning Oriental Aesthetics and Thinking: Conflicting Visions of ‘Asia’ Under the Colonial Empires; the 38th International Research Symposium (pp. 321-33). Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies

Photos

TV Buddha, 1974, Stedelijk.nl

Yellow Peril !, 1963 – 1964, Medienkunstnet.de

Hank Oneal Photo.com

A Tribute to John Cage, 1973-1976, SFMOMA.org

Zen for Head, 1962, multimedialab.be

Tv Buddha, asianjunkie.com

Tv Buddha, Pinterest.com

I have a new post about Nam June Paik at https://steemit.com/art/@bardionson/nam-june-paik-a-robot-sculpture-of-the-south-korean-artist