Inside the Weird, Dangerous World of Japan’s Girl ‘Idols’

The marketing of pop stars (male and female) is a huge business in Japan, generating billions of yen in revenue for the management. It’s sometimes a dirty business as well, with the young idols being used and abused until their “expiration date” has passed or they “graduate.”

Every now and then something brings to light the dark side of the industry; tongues are clicked, bows are made, and things go back to being the way they were.

But when an assault on a member of the popular idol group, NGT48, came to light this year, and the victim then apologized “for creating a commotion,” a storm of outrage blew up—and new revelations surfaced like bombshells washing in with the tide.

As a result, the controversy may finally hit managers in a place that makes them reconsider the way they conduct business: in the pocketbook.

What Are Idols?

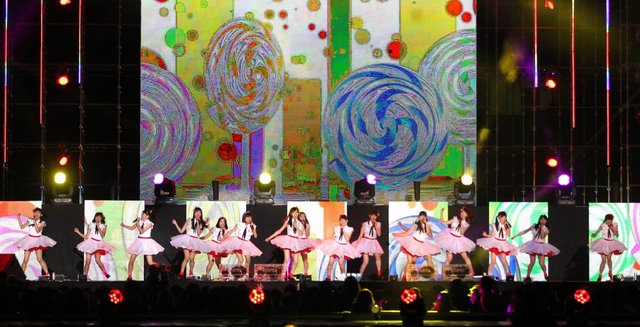

The word “idol” doesn’t have negative connotations in Japan; there are no “false idols,” only profitable ones or unprofitable ones. “Idols” or aidoru refers mostly to the young women and girls who sing, dance, and act for their adoring fans, most of whom are male.

They project an image of purity and friendliness and are touted as role models for many kids. AKB48, the biggest idol group, oddly enough does photo-shoots printed in Japan’s pornographic Weekly Playboy magazine (no relation to the U.S. Playboy) and also had a corner in a newspaper for children.

Idols face tremendous pressure to please their fans and make money for the management. Many sacrifice their adolescence in the process.

Last March, one young idol, aged 16, killed herself. Her parents sued the management company for damages; they also demanded clarification of the events leading up to her death. The case is still pending and a major witness is expected to take the stand on Feb. 18 this year, according to her lawyers.

The latest victim exposing abuse was 23-year-old Maho Yamaguchi. She was in the group NGT48, founded in 2015 in Niigata Prefecture where it has helped bring attention to Niigata and promote tourism. It’s a 48-girl ensemble, and a sister group of AKB48, Japan’s best-known idol group.

On Dec. 8, two 25-year-old men attacked Yamaguchi in front of her home, grabbing her by the face and roughing her up. The Niigata Prefectural Police came to the scene and arrested the two men on assault charges. The men claimed that they were just eager fans and although the police filed charges, the Niigata prosecutor’s office decided on Dec. 28 not to indict. The two men were let go.

The case was not reported in the news; the Niigata police made no announcement.

Yamaguchi, apparently frustrated with the cover-up and the lack of protection from her own management, a firm known as AKS, publicly uploaded a video on social media on Jan. 8 tearfully explaining what had happened.

She said, “I can’t remain silent because this might happen to other members... I’d like to tell the whole truth but I can’t. They [the managers] said they’d get rid of the bad members but they don’t. I can’t bear to think of other members having the same terrifying experience, at least I was lucky this time and was saved [by someone].”

On her Twitter account, she went into further detail, although most of the tweets later were taken down.

Not only did Yamaguchi reveal that she had been assaulted, she implied that another member of her own group was involved in the attack. The management later admitted that one of her co-workers had revealed to the attackers her personal details including what time she usually came home.

It’s not clear who, if anyone, urged the men to attack her, although former idols suggest that rivalry among the girls is so fierce that it wouldn’t be out of the question for one girl to orchestrate an attack on another.

In this case what was was revolutionary was an idol coming forward to tell her story—and criticize the management while doing it. In Japan’s extremely crooked entertainment world, that would usually result in banishment.

Amina Du Jean, a former idol now studying sociology in England, says, “It’s a godsend that Yamaguchi has had the courage to speak up. We’re now seeing idols from all across the board speaking out. While crazed fans aren’t the overwhelming norm, when they do overstep boundaries, idols are often told to be a neutral party to maintain their public persona. What Yamaguchi Maho and the other idols have done by coming out now is groundbreaking. You would’ve never seen this before in the old days with Onyanko Club [a mega idol group in the 1980s]. It would’ve been career suicide. Really, social media has allowed for this to happen.”

The whole story, with all the elements of mystery and cover-up, made Japan’s cybersphere explode with speculation and outrage. If you watch the video of Yamaguchi tearfully and sincerely pleading her case, it is indeed heartbreaking.

With her story out in the open, Japan’s public broadcaster, NHK, and other news outlets picked up the news, reporting on the assault and that the Niigata police had indeed arrested two young men who were not indicted.

The NGT48 management company, AKS, remained silent. Then, on Jan. 10 at a concert celebrating the anniversary of the group’s founding, Yamaguchi took the stage publicly and apologized for “causing a commotion.”

Many fans thought the apology must have been forced. They shouted encouragement for her and anger at AKS: “You’re not the one at fault! They are!”... “You don’t need to apologize!”... “Don’t give up!”

AKS posted a comment on its homepage but the controversy just keeps going. On Jan. 12, weekly magazine Bunshun published a detailed report online, including a chart explaining who was involved in the assault and hypothesizing about what really happened.

By Jan. 14, AKS held its first press conference to address the matter. Its spokespeople were not very convincing.

Executives of the AKS, who manage the NGT48, attend a press conference after Maho Yamaguchi of NGT48 was attacked by fans in front of her house on January 14, 2019 in Tokyo, Japan.

The Asahi Shimbun/Getty

We reached out to AKS for comment and eventually were referred to its most recent posting on the official NGT48 website. In a press release which translates with the title, "Concerning the series of disturbances related to Maho Yamaguchi," the management apologized for “causing problems for the fans of NGT48 and making them worry.”

It responded to allegations of a team member being involved in the attack by saying that if there had been an accomplice the Niigata police would have filed charges on more than two men with the prosecutors. They did vaguely state that there might have been inappropriate words and actions by other girls.

AKS has pledged to set up an independent committee to look into the matter, clearly hoping the story will die.

On Jan. 20, the managers of NGT48 published a message directed to the mass media: “There has been much reporting that is going too far, talking to neighbors, speaking to family members, late night visits… Please restrain yourselves from overzealous coverage as this is stressing the family members, and violating privacy.”

It is also stressing out Yasushi Akimoto, the man pulling the strings of both NGT48 and AKB48.

While the media have been pounding AKS management, very few Japanese periodicals have been willing to question the responsibility of Akimoto, the man in charge of the AKB48 group, of which NGT48 is a subsidiary. But he is the ringmaster of the idol circus.

AKB48 was founded in 2005 by Yasushi Akimoto and his partner Kotaro Shiba. Shiba, according to police sources and reports by weekly magazines in Japan, was an associate of the Yamaguchi-gumi Goto-gumi crime group, and a former loan shark. AKB48 management has never offered a denial. The Goto-Gumi disbanded in 2008. AKB48 continues.

Some of the group’s business practices are reminiscent of the yakuza, who are adept at milking people out of their money by any means possible.

From the start, the group has been a massive money-making machine, and the prototype for other groups. AKB48 has 48 members ranging from 12 to 26 years of age. They perform daily at the AKB48 stadium in Japan’s otaku mecca, Akihabara, and generate millions of dollars for their production company. (Otaku is a broad term used to refer to avid fans of Japanese anime, idols, cosplay, and manga.)

According to labor rights activist and author Shohei Sakagura, little of that revenue reaches the girls working for the firm, and upon “graduating” (getting too old to be an idol) many of them have few job skills, having wasted their best academic years in a low-paid job. Some of the girls have drifted into pornography and other less savory professions.

In order to foster the fantasies of the male fans, the girls are forbidden to have boyfriends, lovers or any kind of sexual relations. This encourages the idea of virtual love: gijiai.

Idols who are caught falling in love have had their heads shaved and made public apologies. Idols have been sued by their managers for daring to have loved someone. The problem is so bad that even a Japanese judge once reprimanded a managing firm, ruling that, “forcing a woman to abstain from loving someone as part of a contract is a violation of basic human rights” and rejected their lawsuit.

While the girls can’t have boyfriends, they can have contact with their admirers, at a distance.

The girls often have “handshaking events” with their fans, in which the sweaty young and old males who idolize these girls get to touch their idols— for a price of course.

In May 2014, a mentally ill man with a folding-saw injured two young AKB48 girls and a staff member at one of these events. The events were stopped for roughly three months before reopening.

The day before the official announcement that the handshaking (and money-making) would start again, Akimoto did an interview with the Yomiuri Shimbun in which he proclaimed, “These girls who have been injured have decided to stand up and go forward,” framing the decision as a courageous act.

The Yomiuri Shimbun and many other companies have been happy to avail themselves of the marketing power of AKB48. The group is a big draw and manages to sell millions of CDs–(yes, CDs!)–every year when they release a new song.

That’s because with each copy of the CD is a ballot to vote in the AKB48 general elections. The number of votes are used to rank the popularity of the group’s many vocalists and dancers. The higher an idol’s rank, the more prominently her singing and dancing is supposed to be showcased in AKB48 performances and future songs. Fans can vote for their favorite AKB48, SKE48, NMB48 or HKT48 members multiple times. They have to buy a CD for each vote.

The group’s newest song, “Teacher, Teacher,” went double platinum, with over 2.5 million CDs sold in two days.

Most of the CDs ended up being tossed in the garbage.

AKB48 members are usually tossed in the garbage only after they become too old, too independent, or too troublesome.

It seems that the outspoken Yamaguchi is headed for the trash heap already. Before the concert on Jan. 10, AKS management contacted reporters at tabloid newspapers and suggested that Yamaguchi was mentally ill, hoping to discredit her in advance.

In this most recent scandal, it’s not only the fans that are angry about the way Yamaguchi has been treated; so is the general public. Even companies are starting to notice. One in Niigata Prefecture, Ichimasa, which is famous for its kamaboko (processed seafood) products, had been using NGT48 in its commercials. After the scandal broke, the company announced that it would be pulling the ads for the time being, and its stock price shot up 46 yen. The media reported that Ichimasa had gained public favor for reacting to the crisis faster than NGT48 management.

The Niigata Chamber of Commerce took out of public domain a video that had featured NGT48. Other local businesses that have been using NGT48 in promotions also are reconsidering their use of the group.

In press conferences, the media has even been questioning why the Niigata prosecutors dropped the charges. The Niigata police made the arrests and investigated the case, but the prosecutors let the alleged assailants go free. People wonder why.

Of course, in Japan, many cases of non-sexual assault against women are not indicted. In cases involving sexual assault, only one out of five women even go to the police, knowing that the odds there will be a serious investigation are slim, and the odds of an actual indictment 50 percent or less.