Pro-poor = pro-growth, turns out

When I was 24 years old, the 1990s had just ended, and I was in Botswana on a USAID project. An Australian economist said to me, "It's ok to be a Marxist when you're in your twenties. In fact, if you're not a Marxist when you're in your twenties then you haven't got a heart. However, if you're still a Marxist when you're forty, then you haven't got a brain."

It was a turbulent time, mentally, for me. My background was in the liberal arts, but I wanted to do much more than sit around and be jaded and world-weary, or to conjure up emotional, self-indulgent notions of changing the world which go nowhere (which is mostly what, it turns out, a liberal arts degree is good for).

It was June, 2001, to be more specific. The infamous terrorist attacks that would come three months later have so transfigured all subsequent remembering that it is very difficult, nowadays, to put oneself in a June 2001 frame of mind. But let's try. Economic neo-liberalism was at the apex of its momentum. Our fearless leaders at the World Bank and IMF, intoxicated with the idea that "capitalism" had recently triumphed over "communism", commanded developing nations to slash their social safety nets and throw open their markets, or else. There was talk of the "end of history". You could hardly go anywhere without someone shoving the "Lexus and the Olive Tree" or "The Wealth and Poverty of Nations" in your face.

And so this was the turbulent thing. With a heart full of Kafka, Marcuse, and Foucault, I set out to comprehend Friedman, Greenspan, and Fukuyama. This was intellectually painful because, as a general rule, the Marcuses and Foucaults (and such) of the world anticipate and describe the Fukuyamas and Greenspans with startling exactitude; while the curators of the conventional wisdom (the neoliberal policy wonks in this case), on the other hand, demolish armies of straw Marcuses and Foucaults with sickening, animal farm arogance--which they (and their New York Times "critics") then mistake for analytical prowess--oftentimes without ever having read the works of their targets.

The rest is (a very sad) history. Marx said that history always repeats itself--first as tragedy, second as farse. But it seems to me there is something about this latest incarnation of well-worn historical cycles that is both tragic and farsical--and not in a hip, Samuel Beckett way, nor in any other remotely redeeming way.

Anyways, you don't hear much from the trickle down people these days. You'd hardly know they ruled the world a short time ago. Oh, and hey, you wanna know two books that no one is shoving in my face anymore? (Figure 1)

Finally, terms like "pro-poor" and "financial inclusion" are moving to the center of mainstream development discourse. Most importantly, I think, are a crop of recent (IMF-funded!) studies that put to rest the horseshit about a "rising tide lifting all boats". On the contrary, the data show that growth has no impact, positive or negative, on income inequality. Moreover, the findings show that capital-intensive growth spells which exclude large sections of society tend to be fragile and short-lived, whereas labor-intensive growth spells with large participation from society are relatively robust and long-lived (Berg & Ostry, 2011; Berg, Ostry, & Zettelmeyer, 2012; Dabla-norris & Kochhar, 2015; Ostry, Berg, & Tsangarides, 2014).

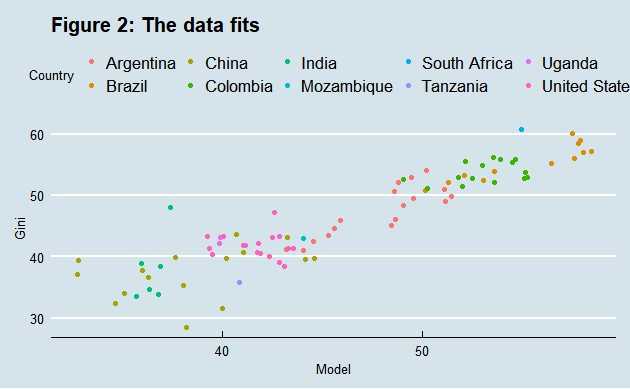

There is enough data lying around these days that you can readily check this for yourself. Using the World Bank's World Development Indicators (WDI) and the United Nations University Income Inequality Database (WIID 3.4), I estimated income inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) as a function of growth, rural population size, education and age of population, R&D expenditures, and natural resource rents (see table and Figure 2 below). The model is in logs, so the coefficients reported below can be interpreted as percentage impacts on inequality.

The coefficient on the growth variable ("GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$)") is zero, confirming the recent work metioned above. Inequality is "growth-neutral", i.e., growth, generally speaking, does not "lift all boats", nor do its benefits "trickle down", nor any such nonsense.

The coeffients on the control variables are what we'd expect, indicating inverse relations between income inequality, on the one hand, and education and R&D investments on the other. The coefficient on the population youth variable is also to be expected, considering that young populations are often symptomatic of broken or non-existent healthcare systems, one of the more obvious hallmarks of deeply dysfunctional, impoverished nations. Basically, these three coefficents are just your standard, glaringly obvious evidence in favor of government investments in education, science, and healthcare.

Turning to the natural rents and rural population variables, we find an even more damning statement about the relation between growth and inequality. I wasn't at first sure how to interpret the rural pop. variable. In my experience, large rural populations are usually associated with highly unequal societies in Africa. However, considering that agricultural/food systems are naturally labor-intensive sectors with high participation from the lowest centiles of the income distribution, I think it's fair to interpret this variable as a proxy for the relative size of labor-intensive, socially inclusive sectors in the economy. Conversely, the natural rents variable can be interpreted as a proxy measure of capital-intensive, socially exclusive growth.

The coefficients on these variables therefore indicate a 70% correlation between inequality and socially exclusive growth, and a 38% correlation between equality and socially inclusive economics. This goes beyond the growth-neutral statement. This says that--not only does growth generally not lift all boats--capital intensive forms of growth may cause many boats to sink.

References

Ostry, J. D., Berg, A., & Tsangarides, C. G. (2014). Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth. IMF Staff Discussion Note, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484352076.006

Dabla-norris, E., & Kochhar, K. (2015). Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality : A Global Perspective. IMF Staff Discussion Note. https://doi.org/DOI:

Berg, A., & Ostry, J. (2011). Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin? International Monetary Fund Staff Discussion Note, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Berg, A., Ostry, J. D., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2012). What makes growth sustained? Journal of Development Economics, 98(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.08.002