Rory End to the Regginbrow

In the seventh clause of Finnegans Wake’s second paragraph, James Joyce combines Biblical imagery and Irish history for the fifth and final time. The first draft, however, contains no allusions to Irish history:

& bad luck to the regginbrew was to be seen on the waterface. (Hayman 46)

This passed through four successive drafts before Joyce hit upon the definitive version. It was only in the fourth draft that Joyce finally found a way of including a piece of Irish history:

& worse end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsun the waterface.

& bloody end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsun the waterface.

& rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome the waterface.

and rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome on the waterface.

(Hayman 46)

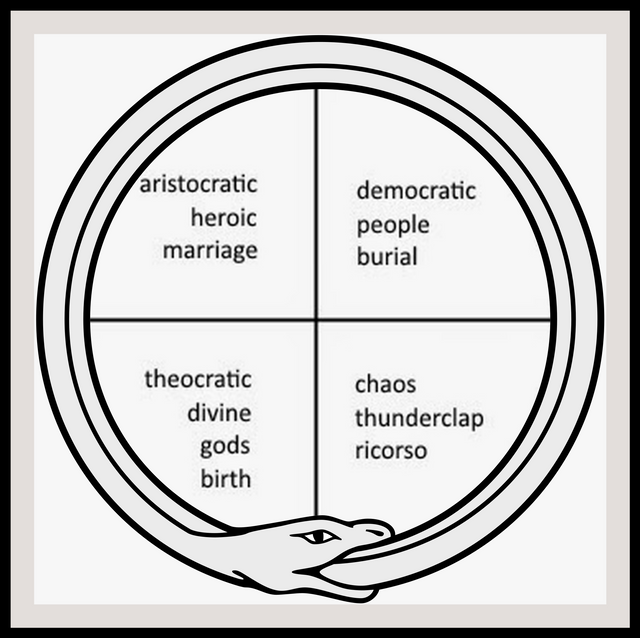

Beginnings and Endings

The overriding theme of Finnegans Wake is the endless cycle of human life and history. The fall of one generation always coincides with the rise of the next generation. This is embodied in Giambattista Vico’s cyclical philosophy of history, in which beginnings and endings coincide. It is captured visually by the ouroboros, the image of a serpent swallowing its own tail. So it is entirely appropriate for Joyce to end this paragraph by bringing us back to the Creation of the World and the opening chapter of the Bible:

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. (Genesis 1:2)

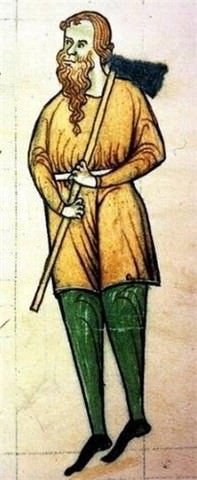

And with the very same words with which he invokes the beginning of one world Joyce laments the end of another world: rory end alludes to Rory O’Conor, the last High King of Ireland, whose reign coincided with the Anglo-Norman Invasion of Ireland and the loss of native independence:

“Rory” connotes Rory O’Connor who was High King of Ireland when the royal brow [regginbrow = regal brow] of the conqueror, Henry II, came up over the eastern [rory end = orient] horizon. This brow was the coming of a new age, as was the rainbow [German: Regenbogen] in the time of Noah. (Campbell, Robinson & Epstein 29)

Over the centuries, this man has been known by many names:

- Ruadri Ua Conchobair

- Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair

- Ruaidhrí Ó Conchobhair

- Ruairí Ó Conchúir

- Rory O’Connor

- Rowrie O’Conor

- Roderic O’Connor

- Roderick O’Connor

- Roderick O’Conor

Joyce seems to have preferred the latter, Roderick O’Conor, so this is the form I will use.

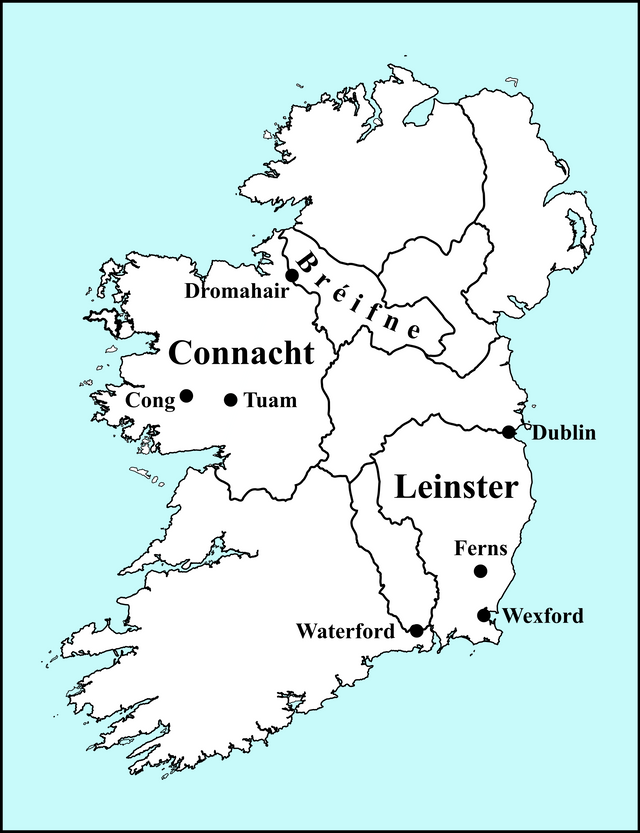

Roderick was born around 1116, probably in Tuam. His father, Turlough O’Conor, was King of Connacht. When Roderick was four years old, Turlough became High King of Ireland “with opposition”—he claimed the kingship by force of arms, but his claim was not universally acknowledged. Turlough was a fecund individual: he was married at least six times and fathered more than two dozen children. Roderick and his sister Mór were the only issue of Turlough’s third marriage, to Cailech Dé Ní hEidin.

In 1136, Roderick and his half-brother Aedh staged an unsuccessful rebellion against Turlough. Aedh was blinded for his trouble, but Roderick was protected from his father’s wrath by the Archbishop of Connacht. Seven years later, Roderick again tried to unseat his father. This time he was imprisoned for a year before the intercession of the clergy secured his release.

When Turlough died in 1156, Roderick succeeded him as King of Connacht. The next ten years were spent in unremitting conflict with his rivals, but by the end of the decade Roderick had made himself the most powerful man in the country. In 1166, he was inaugurated as High King of Ireland in Dublin. He was fifty years old at the time. Like his father before him, he had no hereditary right to the crown, but claimed it by force of arms.

Roderick had the misfortune, however, to back the wrong horse in a domestic dispute between two powerful rivals, Diarmait Mac Murchada (Dermot MacMurrough) and Tigernán Ua Ruairc (Tiernan O’Rourke). This feud, which Mr Deasy discusses with Stephen Dedalus in the Nestor episode of Ulysses, furnished Henry II of England with a pretext for invading Ireland.

The story is a complicated one and the details are still disputed, but the best authenticated version has it that it was this way:

Tiernan O’Rourke is the King of Bréifne, a small kingdom roughly encompassing the modern counties of Leitrim and Cavan. In 1126, Dermot MacMurrough becomes the King of Leinster. He is only sixteen at the time. Turlough O’Conor is High King of Ireland and fearing this young rival, he and his liegeman Tiernan invade Leinster to remove him. Their campaign is bloody and brutal, and Dermot is forced to flee. Six years later, however, he is restored with the help of his allies in Leinster. There follow two decades of uneasy truce, during which Dermot and Tiernan sometimes find themselves fighting on the same side against a common foe.

Fast-forward to 1152: Tiernan is now an enemy of Turlough’s and it is Turlough and Dermot who are ravaging Tiernan’s kingdom. Revenge is sweet. Dermot rubs salt into the wound by carrying off Tiernan’s wife Derbforgaill (Derval) and all her possessions. Over the next fourteen years, Dermot consolidates his power in Leinster. By 1162 he is even powerful enough to depose the Norse King of Dublin, Asculf, and make himself ruler of the fledgling city.

It is now 1166. Turlough is dead and his son Roderick has made himself master of the island. Dermot’s only powerful ally, Muircheartach Mac Lochlainn, who had succeeded Turlough as High King, has just been killed in a separate dispute. The time is ripe for Tiernan’s revenge. Together, Roderick and Tiernan march on Dublin. Asculf is restored, and Roderick is crowned in the city as the new High King of Ireland. Dermot is formally deposed from the Kingship of Leinster: his abduction of Derval fourteen years before is commonly cited as justifying his deposition:

Since the days of Adam, there has been hardly a mischief done in this world but a woman has been at the bottom of it. (Thackeray 5)

Despairing of his Irish allies, Dermot flees to Britain and then to Aquitaine, where he enlists the aid of Henry II. In 1167 Dermot returns to Ireland with an army of Norman knights at his back. Because of this, he will be forever cursed by Irish tongues as the man who let the English rat into the house.

In 1170, reinforcements arrive at Bannow Bay in the south of Leinster. They are led by Strongbow, also known as Richard de Clare, the 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Dermot has promised the hand of his daughter Aoife to this dangerous and ambitious warlord, and he makes Strongbow his heir, or tánaiste. The Norse city of Waterford is stormed and taken, and Strongbow is married to Aoife amidst the ruins. Dublin is subsequently captured and Asculf is again deposed.

The following year, 1171, Dermot dies and Asculf is killed attempting to retake Dublin. In the same year, Roderick besieges Dublin but his army is surprised by a sally and routed. Four years later, after defeating Strongbow at Thurles and ravaging Munster, he comes to terms with the foreigners. Roderick acknowledges Henry II as his liege lord, and in return he remains King of Ireland. But this fails to establish peace, as several warlords—both Irish and Norman—consider Roderick’s titles fair game. Among his most formidable enemies are his own sons Murchadh and Conchobhar, who try to depose him. The former loses his sight for his trouble, and the latter his life. Finally, in 1191, Roderick is successfully challenged and deposed by his younger half-brother Cathal O’Conor. He retires to a monastic life in Cong Abbey, Galway, where he dies in 1198 at the age of eighty-two.

The End.

Grist to the Mill

Familial strife figures prominently in Finnegans Wake. The paternal and filial conflicts in Roderick’s life resonate throughout the book and are perfect analogues for the Viconian conflicts in HCE’s life: the struggle between Roderick and his two sons is the struggle between HCE and his sons Shem and Shaun : the struggle between Roderick and his half-brother Cathal is the struggle between the two rival brothers themselves.

The abduction of Tiernan’s wife and its tragic consequences echo the epic story of the Fall of Troy. History repeats itself, as Vico teaches us. The Tiernan-Derval-Roderick triangle is the familiar isosceles triangle in which Shem and Shaun vie for the love of their sister Issy.

The story of the deposed leader going into exile, raising a foreign army, and returning to Ireland in triumph is a common one in Irish history and mythology, and it provides Joyce with another important leitmotif to explore.

And finally, the marriage of the Irish princess Aoife to the foreign warrior Strongbow brings us back to Sir Tristram, whose penisolate invasion of Ireland opened this pregnant paragraph. That Aoife is the Irish for Eve and that her and Strongbow’s daughter was called Isabel are just two more of those happy little concurrences in which Finnegans Wake abounds.

Roderick O’Connor Vignette

If you have been following these articles from the beginning, you may remember that the very first thing Joyce wrote after the publication of Ulysses was a short sketch—or vignette, to use the preferred term—in which Roderick O’Conor is portrayed as an innkeeper. After the departure of his customers, he drinks the heeltaps from their glasses before falling asleep in a chair.

The original draft was written in March 1923:

So anyhow to wind up after the whole beanfeast was all over poor old King Roderick O’Conor the last king of all Ireland who was anything you like between fiftyfour and fiftyfive years of age at the time after the socalled last supper he gave or at least he wasn’t actually the last king of all Ireland for the time being because he was still such as he was the king of all Ireland after the last king of all Ireland Art MacMurrough Kavanagh who was king of all Ireland before he was anyhow what did he do King Roderick O’Conor the respected king of all Ireland at the time after they were all of them gone when he was all by himself but he just went heeltapping round his own right royal round rollicking table and faith he sucked up sure enough like a Trojan in some particular cases with the assistance of his venerated tongue one after the other in strict order of rotation whatever happened to be left in the different bottoms of the various drinking utensils left there behind them by the departed honourable guests such as it was either Guinness’s or Phoenix Brewery Stout or John Jameson and Sons or for that matter O’Connell’s Dublin ale as a fallback of several different quantities amounting in all to I should say considerably more than the better part of a gill or naggin of imperial dry and liquid measure.

Roderick was about fifty-five when he bent the knee to Henry II (1171), and Dermot was about fifty-five when he was forced into exile (1166).

The appearance of Art MacMurrough Kavanagh is a bit of a mystery. This man lived in the 14th century, about two hundred years after Roderick. He was never High King of Ireland, though he was for a time the most powerful man in Leinster. It is possible that Joyce has simply misplaced him. Joyce was not a historian and this would not be the first time he got such details wrong. In Ulysses, when Mr Deasy speaks of the feud between Dermot and Tiernan, he says:

A faithless wife first brought the strangers to our shore here, MacMurrough’s wife and her leman O’Rourke, prince of Breffni. (Joyce 2000:43)

If you have been paying attention, you will know that Mr Deasy has the wrong sow by the lug: Derval was O’Rourke’s wife, not MacMurrough’s. And we do not know if she was ever MacMurrough’s leman (lover). But who is in error here: Mr Deasy or Joyce? I believe Joyce is the one who does not know his history, and the reference to Art MacMurrough Kavanagh as High King of Ireland before Roderick O’Connor bears this out.

A later draft of this vignette eventually found its way into Finnegans Wake, but it will be a long time before we get to it!

References

- William Makepeace Thackeray, The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq, Collins’ Clear-Type Press, London (1900)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, Edmund L Epstein (editor), A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, New World Library, Novato CA (2005)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), The Encyclopaedia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 23, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1911)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin TX (1963)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- Sidney Lee (editor), Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 41, Smith, Elder & Co, London (1898)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

Image Credits

- The Creation of the World: WikiArt, Ivan Aivazovsky (artist), Public Domain

- Viconian Ouroboros: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain, Tim Finnegan, Fair Use

- Roderick O’Conor: Wikimedia Commons, Stone Carving at Cong Abbey, Public Domain

- Dermot MacMurrough: Midleton with 1 “d”, Anonymous Illustration, Public Domain

- The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife: Daniel Maclise (1806-1870), The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife, 1854, © National Gallery of Ireland, Fair Use

Useful Resources

its so informative, thanks @harlotscurse dear.

@upvote done

its informative post, thanks for share.

@upvote done

your post are so informative. thanks for share with us

hi dear @harlotscurse

i am new your blog..thanks for sharing✌✌

i just waliting for your article.really great one

also informative post

upvote @resteem

one of the best literature..thanks @harlotscurse

@upvt @resteem

awesome photography..also your literature is the bes!💘💜

@upvotev@ resteem done

what a literature!!just awesome friend😍

you always share the best article.God bless you.

resteemed

informative post for us

@follow @upvt @resteem brother