Children First: Building a Global Agenda by Audrey Hepburn (1992)

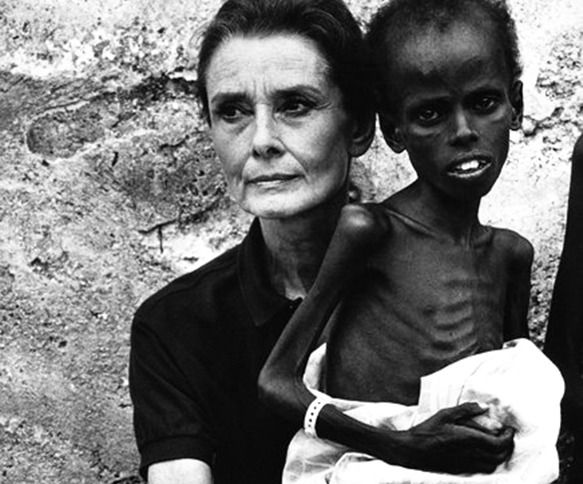

Just a year before she succumbed to to colon cancer, Audrey Hepburn stood before an audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco looking as iconic and effortlessly noble as the 50-year-old Breakfast at Tiffany’s posters that still adorn cafés and apartments the world over. She delivered a speech on the future for children on this planet and her experiences as a UNICEF Ambassador.

She tragically suffered at least five miscarriages throughout her life, but through her work as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador she refocused these unspent maternal energies on trips to orphanages in Mekelle, Ethiopia and refugee camps in South Sudan, assuming the role of a global matriarch.

As touching as her words are, looking back at her aspirations in hindsight highlights a huge disparity between her vision and the reality of the world that has transpired since she passed. She called to roll back the $150 billion a year Western arms budget; last July US Congress voted decisively to increase their defence budget to almost $700 billion a year, and the annual spend of the UK, France and Germany alone reached $150 billion in 2017.

The UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadorial role remains to this day, currently held by stars such as Lionel Messi and Femi Kuti.

Children First: Building a Global Agenda by Audrey Hepburn (1992)

Until four years ago when I was given the great privilege of becoming a volunteer for UNICEF, I, like all of you, was overwhelmed by a sense of helplessness when watching television or reading about the indescribable misery of the children and their mothers in the developing world. If I feel less helpless today, it’s because I have now seen what can be done, and what is being done by UNICEF, by many marvellous agencies, churches, governments, and most of all, with very little help, by people themselves.

Today we stand at the crossroads: Our world has changed dramatically in a short time, and we must now plot a new course for the future. I’m here on behalf of UNICEF to talk about where children fit into the new course, to talk about priorities. We have to recognize that children have not been our greatest priority, but they must be. And if we seize the opportunity now before us, they really can be.

I was among the first recipients of UNICEF aid after World War II, which is why I have such a deep, personal appreciation for UNICEF. Mine was the first generation to live in the ominous shadow of the nuclear age, and we were the first children to grow up with the term “Cold War” and all its divisive and paranoid implications. We had survived the bombing of Europe only to find ourselves, in a very real sense, coming of age in another war, the costs of which were very steep indeed.

Deaf ears

This conflict between East and West soon became a political framework for the entire globe. The superpowers intervened in developing countries in order to gain territorial advantages, and rival factions in these countries were all too willing to choose sides in exchange for support in their internal struggles. The prevailing world order was marked by barricades, real and imaginary, and it fostered a mentality of us versus them. The real losers, of course, were the children: the children of Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East who suffered from daily neglect. The choice between guns and bread had never been more immediate nor lopsided as it was during the height of the Cold War.

UNICEF, the world’s leading voice for children, tried to protect them. UNICEF reminded governments time and again that the needs of children were urgent and the most important, but its warnings fell on ears that were either deaf or simply too preoccupied to listen. When I first became involved with UNICEF, the organization that had meant so much to me and many other children in post-war Europe, I didn’t think I’d live to see the end of that bitter struggle. Like the children of countries like Lebanon and Mozambique, who have known little peace, I had grown up with the Cold War, and it was part of all of our lives.

Then, and it seemed to happen overnight, the world changed dramatically. Like the Berlin Wall and the Soviet empire, the old order has come tumbling down. We now have something that is so rare in the course of civilization: a second chance.

Quiet catastrophe

Now, more than 45 years after it pleaded with the world to remember its children, UNICEF is once again making the case for our next generation. As the new world order comes into focus, UNICEF is reminding the world’s leaders of the devastating realities. While the world was busy fortifying the ideological chasm that divided it, the children have been paying for it with their lives: 40,000 a day, 15 million a year. No earthquake, no flood, ever claimed 40,000 children on a single day. Though these children are the quiet catastrophe and never make headlines, they are just as dead. By any measure this is the greatest tragedy of our times. They’ve been dying from preventable diseases, including measles and tuberculosis. They’ve been dying in wars, caught in the cross-fire of those who should have been protecting them. They’ve been dying for lack of proper nutrition when the world has more than enough food. They’ve been dying from dehydration caused by diarrhea more than from any other single cause because they don’t have clean drinking water.

World Summit for Children

In September of 1990, when the old world order was showing signs of collapse, UNICEF hosted 71 heads of state at the World Summit for Children in New York to address the appalling situation of children. The summit yielded a historic agreement on specific goals to help children by the year 2000. In its latest message to the world’s leaders, UNICEF released its 1992 State of the World’s Children Report. In this year’s report, UNICEF offers 10 agenda items for the formation of a new world order.

I won’t talk about all the specific propositions, but I would like to mention a few of them:

a) That the promises of the World Summit for Children be kept. These include a one-third reduction in child deaths, and a halving of child malnutrition by the year 2000.

b) That demilitarization should begin in the developing world, and that falling military expenditures in the industrialized countries should be linked to increased, unconditional international aid and the solving of global problems. Currently, developing countries spend about $150,000 million on arms each year. Meanwhile, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council sell 90 per cent of the world’s arms. What does this mean? It means that we are entrenched as a global community in a destructive cycle of weapons proliferation. Achieving all of the summit goals would require some $20,000 million a year, an amount equal to two-thirds of the developing world’s military spending, and just 1 per cent of that in industrialized countries.

c) That the growing consensus around market economies be accompanied by a commitment to a strong investment in people, especially children. Simply put, this means that there are things that a free market alone cannot do. Governments must combine free-market forces with assurances of health and education for all, especially children, even in bad economic times. The importance of this proposition is not limited to developing countries. As UNlCEF’s report also points out, the situation of urban and poor children in the United States continues to worsen. Child poverty is on the rise, and the real value of Aid to Families with Dependant Children has dropped 40 per cent in the last 20 years. Even here, in the country that is the world’s model of a free economy, we are slow to realize that all children do not benefit from that system. We must build what amounts to a safety net to catch these children before it is too late. There are some encouraging signs that the world’s leaders may listen this time. The World Summit for Children is clearly one of them. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child has now been ratified by 107 countries, and more than 30 others have signed it with the intention to ratify.

Miracle of the decade

Last October I was at the United Nations with President Carter and other dignitaries when UNICEF and the World Health Organization certified to the Secretary General that they and the world’s governments had achieved their goal of universal child immunization by 1990. This is the miracle of this decade. This does not mean that we have immunized every child or that every country is winning the battle with vaccine-preventable diseases. It does mean that 80 per cent of the world’s one-year olds have been immunized against the six major child-killing diseases: measles, tuberculosis, tetanus, whooping cough, diphtheria, and polio. This effort is saving some 3 million young lives each year.

In 1974, less than 5 per cent of the developing world’s children were vaccinated. It’s difficult to grasp the full meaning of these successes until you’ve looked into the eyes of these children who can too often be numbers. Rather than share with you the horrors I’ve witnessed, I prefer to remind you of how easy it is to reach out and help these children. There has never been a better opportunity to give our children the future they deserve. We have low-cost technologies like immunization and oral rehydration therapy. We have ample resources made available due to the end of the Cold War, and we have the commitment of the world’s leaders. What remains is for us to change our attitudes as a society, to build a movement for children, and to ensure that the promises of the World Summit for Children are kept.

Twenty years ago, few people thought about recycling their newspapers, few people worried about the effect of hair spray on the ozone layer, few people questioned the amount of pollution their cars were spewing into the atmosphere, but slowly and effectively the environmentalists in this country and around the world built a movement that could not be ignored, and they have brought about a fundamental change in the way we live our lives and the way we see our planet. We have taken responsibility for our neglect. So too must we take responsibility for the neglect of our children. So too must we effect a basic change in our priorities and concerns. We must resolve ourselves as a community to put the needs of children first in war and in peace, in good times and in bad.

So today, I speak for children who can’t speak for themselves, children who are going blind from lack of vitamins, children who are slowly being mutilated by polio, children who are wasting away in so many ways from lack of water. I speak for the estimated 100 million street children in this world, who have no choice but to leave home in order to survive, who have absolutely nothing but their courage, their smiles, their wits, and their dreams; for children who have no enemies, yet are invariably the first tiny victims of war, wars that are being waged through terror, intimidation, and massacre; for children who are therefore growing up surrounded by the horrors of violence; for the hundreds of thousands that are refugees; and for the rapidly increasing number of children suffering from or orphaned by AIDS.

The great task ahead

The task that lies ahead for UNICEF is ever great, whether it’s repatriating millions of children in Africa or Asia, or teaching children how to play who only have learned how to kill. Children are our most vital resource, our hope for the future. Until they can be assured of not only physically surviving the first fragile years of life, but are free of emotional, social, and physical abuse, it’s impossible to envisage a world that is free of tension and violence. It is up to us to make it possible. Charles Dickens wrote: “In their little world, in which children have their existence, nothing is so finely perceived and so finely felt as injustice” injustice which we can avoid by giving more of ourselves. Yet we often hesitate in the face of such apocalyptic tragedy. Why, when the way and low-cost means are in place to safeguard and protect these children? It is for leaders, parents, and young people – young people who have the purity of heart which sometimes age tends to obscure – to remember their own childhood and come to the rescue of those who start life against such heavy odds. Simply because they are children, every child has the right to health, to education, to protection, to tenderness, to life.