Tagore, India and Kashmir

The poet’s imaginary had special and poignant resonance for Kashmir. He would undoubtedly agree that Kashmir never pursued a borrowed history; it lived and was faithful to its own

Much has been written on Kashmir’s deepening darkness. The mobilisation around the future of Article 35A that the Kashmiris correctly read as an attempt to destroy Kashmiri identity through the dispossession of Kashmiri land is the inevitable outcome of seven decades of political attrition against expressions of (ethnic) difference in general. Indeed, the erosion of the protections of Article 370 by ‘secular’ regimes paved the way for the present assault on the last remaining remnant of Kashmiri identity by a right-wing dispensation.

The Indian state’s dogged pursuit towards erasure of all expressions of ethnic and/or cultural ‘difference’ – especially in the peripheral areas, including Kashmir – has been a consistent feature of its modern post-colonial life. What explains this impulse? Instead of the usual a historical explanations indicting particular regimes and elite manipulation of ethnic identity for political purposes, this essay ventures into the relatively unexplored deeper ‘why’ underpinning the modern Indian state’s persistent efforts towards effacing or erasing expressions of difference.

India

In his 1918 treatise on nationalism, Rabindranath Tagore reflected that India’s problem was social, not political. Two main criticisms underpinned his observation. Underlining the subcontinent’s racial and ethnic diversity that he accurately characterised as an enduring fact and facet of united India’s history, Tagore argued powerfully for a moral and ethical basis of unity shaped and upheld by the higher instincts of humankind:

“No nation looking for a mere political or commercial basis of unity will find such a solution sufficient…We in India must make up our minds that we can’t borrow other people’s history, and that if we stifle our own we are committing suicide. When you borrow things that don’t belong to your life, they only serve to crush your life.”

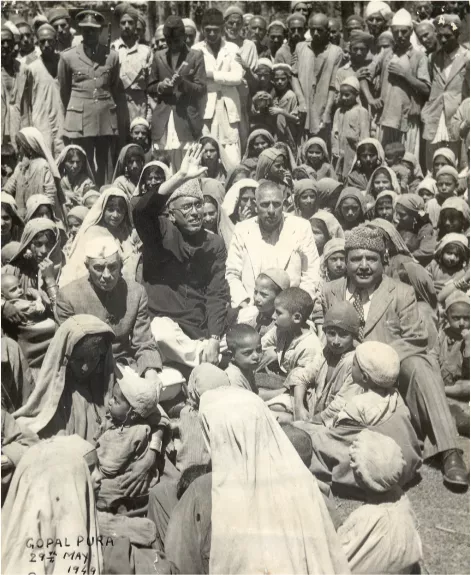

For all his flaws and final surrender, Sheikh Abdullah offered to the Kashmiri people a constructive idea and vision: of radical change in the exploitative relations of production through land reform – an idea to which modern Kashmir owes considerable debt.

Tagore’s humanistic vision of unity for a sub-continental mosaic of communities was based on a deeper, profound understanding and appreciation of sub-continental history that he pointed out, was incompatible with the idea of political unity contained in the construct of the modern (European) nation-state. “India is too vast in its area and too diverse in its races. It is many countries packed in one geographic receptacle.” To mimic or replicate the idea of the European nation-state and its attendant concept of singular nationhood in a context characterised by markedly different histories, and ethnic and racial diversity, plurality and difference, he warned, was to tread the path of despair.

Sadly, there were few takers for Tagore’s words of wisdom and prophecy that subsequently came to haunt the modern Indian nation-state. Movements opposed to the latter’s obsession of political unity and singular identity were sought to be contained through coercion and repression.

Further, Tagore’s far-sighted and astute scepticism of a “nationalism based on harping upon other’s faults and the erection of Swaraj on a foundation of quarrelsomeness” received short shrift from a nationalist leadership including Gandhi. Criticising Gandhi for his launch of a non-cooperation movement involving a boycott of British schools, colleges, courts and the burning of foreign cloth, Tagore cautioned against treading the dangerous and fine line between patriotism and xenophobia.

Almost a century later, Tagore’s admonition and criticism of a nationalism premised on anger and hatred against the foreigner that he warned “could later turn into hatred of Indians different from oneself” transformed into a tragic self-fulfilling prophecy. The killings and lynching of Muslims; the stereotyping of ‘different’ people from the Northeastern region; as indeed the racism and violence against black people mirrored mainland Indian society’s inability to respect or accept racial and ethnic difference. Political unity in the form of a modern nation-state couldn’t impart to Indian citizens the ‘foreign’ albeit universal moral principle of the unity of humanity, or the truly modern ethic affirming the humanity and equal human value of the racial/ ethnic ‘other.’

Inevitably, these social flaws aided by the absence of moral restraint seeped into and coloured India’s political life in destructive and damaging ways. Public hostility towards expressions of difference of views, identity, politics or religious belief undercut every avenue and possibility of social unity. As Tagore put it

“The social habit of mind which impels us to make the life of our fellow beings a burden to them where they differ from us even in such a thing as their choice of food, is sure to persist in our political organisation and result in creating engines of coercion to crush every rational difference which is the sign of life.”

Mohammed Akhlaq, Junaid and Pehlu Khan were among the numerous victims of mainland India’s morally blind patriotism premised on prejudice and violence towards the ‘different’ other.

Anger, violence and hatred for the stranger, the foreigner, or the ‘other’ aren’t civilisational values; on the contrary, violence driven by prejudice mirrors social death, degeneration and decay that, in turn, renders social institutions incapable of humane practice or the administering of justice defined by moral values. Shorn of morality and humanity, institutions transform into rubber-stamps for injustice and tyranny. The present climate of bigotry isn’t a temporary setback to be rolled back at a more opportune or propitious moment. Nor must it be viewed as a problem limited to the state or its institutions. Rather, as Tagore insightfully remarked, it is the culmination of a nationalist politics that wanted only “scraps of things” while lacking a broad constructive vision or ideal:

“The thing we in India have to think of is this – to remove those social customs and ideals which have generated a want of self-respect and a complete dependence on those above us – such as the caste system. Indians complained of colonial arrogance, and yet they treated their own people so badly…in her samaj, in daily practice, India fails to do justice to herself.”

The project of crafting a nation-state around the construct of political unity underpinned by social disunity was, as Tagore accurately pointed out, at the cost of crafting and cultivating a universal human bonding. This was, he acknowledged, no easy task. Yet, an egalitarian social order was a basic and most fundamental pre-requisite towards achieving collective (national) self-respect and genuine equality amidst the world of nations. Sadly however, an inward-looking national imagination that blamed all shortcomings in Indian society to ‘foreigners’ or ‘outside’ influence was ill-suited to the real and compelling needs of Indian society. Tagore justly decried a nationalist imagination wherein:

“The general opinion of the majority of the present-day nationalists in India is that we have come to a final completeness in our social and spiritual ideals, the task of constructive work of society having been done several thousand years before we were born, and that now we are free to employ all our activities in the political direction. We never dream of blaming our social inadequacy as the origin of our present helplessness, for we have accepted as the creed of our nationalism that this social system has been perfected for all time to come by our ancestors, who had superhuman vision of all eternity and supernatural powers for making infinite provision for future ages. Therefore, for all our miseries and shortcomings we hold responsible the historical surprises that burst upon us from outside. This is the reason why we think that our one task is to build a political miracle of freedom upon the quicksand of social slavery.”

Mohammed Akhlaq, Junaid and Pehlu Khan were among the numerous victims of mainland India’s morally blind patriotism premised on prejudice and violence towards the ‘different’ other.

Tagore was a patriot who loved his country, yet his patriotism was starkly different from Nehru and Gandhi because it was rooted in history, humanity and an internationalism affirming the higher moral principle of the unity of humankind. In this imaginary, India was a repository of cultural confluence, a beacon of openness, not exclusion or bigotry, a work in progress demanding sacrifice and commitment, not a nation-state to be flaunted or glorified. Historian Ramchandra Guha summed up the importance of diversity in Tagore’s imagination and aspiration:

“As he (Tagore) saw it, the staggering heterogeneity of India was the product of its hospitality, in the past, to cultures and ideas from outside. He wished this openness be retained and even enhanced in the present. Unlike other patriots, Tagore refused to privilege a particular aspect of India – Hindu, North Indian, upper caste, etc. – and make this the essence of the nation, and then demand that other aspects conform or subordinate themselves to it. For Tagore, as the historian Tanika Sarkar pointed out, India ‘was and must remain a land without a centre’.”

Kashmir

Tagore’s imaginary had special and poignant resonance for Kashmir.

Tagore would undoubtedly agree that Kashmir never pursued a borrowed history; it lived and was faithful to its own. Indeed, the Kashmiri Muslims’ struggle for justice is rooted in Kashmiri history. Unlike mainland India, Kashmir imagined a future based on Kashmiri history and a distinctive culture shaped by its historical, spiritual and cultural confluence with Persia and Central Asia. From both these regions came influences that imbued Kashmir with the moral principles of universality, humanity, tolerance.

Kashmiri Muslim society was subject to divisions by class, caste and sect. Yet at the same time, Kashmir’s social order retained a general cohesion which is why collective historical memory remains strong, powerful. Unlike mainland India, social interaction between Kashmiri Muslims in Kashmir followed a rational pattern in keeping with the ebb and flow of human societies: Kashmiris could marry, dine, befriend, love or shed blood for each other, free of the frozen and congealed caste divisions and restrictions in mainland India.

Also, unlike mainland India, Kashmiri history imparted to Kashmiri society coherence and cohesion; it imbued the people of Kashmir with an outward-looking universalist character – playing host to and being hospitable to strangers, outsiders and foreigners who flocked to partake of Kashmir’s beauty and culture embraced by majestic mountains.

Further, unlike the politics and fires of anger against the ‘foreign’ invader and colonial masters by India’s nationalist elite, Kashmir embarked on its post-feudal journey with a republican imaginary of a people destined to chart a history different from the one under a tyrannical feudal Maharaja. For all his flaws and final surrender, Sheikh Abdullah offered to the Kashmiri people a constructive idea and vision: of radical change in the exploitative relations of production through land reform – an idea to which modern Kashmir owes considerable debt. Mass literacy, education, a professional middle class, the end of an impoverished Muslim underclass, the right to land, agrarian reform were among the abiding achievements of a constructive modernist vision of a Kashmir that steered clear of stoking or spreading the self-destructive fires of anger and violence against others. Further, Kashmir’s prolonged periods of tyrannical foreign rule or indeed the presence of strangers and foreigners on its soil was never perceived as an assault on Kashmiri culture or identity.

For this reason, in contrast to mainland India, Kashmiris never developed a sense of prejudice or bigotry towards non-Kashmiris; nor did Kashmiri society discriminate on the basis of religion, caste, creed or gender. In all these respects therefore, Kashmir’s Muslim society was far more egalitarian, democratic and humane than that of mainland India for whom the rhetoric of political unity and mass democracy served to mask the great contradictions and flaws within its social fabric.

Sadly however, with the formation of bordered, militarised national boundaries the moral, spiritual and cultural streams that had fed and nurtured Kashmiri culture for centuries were stifled; they dried up. Locked in and isolated by geography, partitioned by history, and coveted by two nationalist militarised nation-states, Kashmir could never prosper. As Kashmiris sought to safeguard their identity shaped by Kashmiri history, mainland India’s rulers insisted on foisting an ahistorical, culturally denuded political identity on a people far removed from India’s politics, history or culture. The inevitable clash between the Kashmiri and the ‘national’ could never be resolved because the ‘national’ was unaccepting of the Kashmiri cosmology of self-identification.

Kashmiri insistence on the protection of Kashmiri culture and identity was disciplined and punished through coercion and repression. As power became the currency of dominance over Kashmir, mainland India’s nationalist hysteria revealed the extent of India’s moral degeneration. Tagore’s reflection on nationalism summed up the great moral chasm between political freedom in mainland India and collective repression and misery in Kashmir:

“The narrowness of sympathy which makes it possible for us to impose upon a considerable portion of humanity the galling yoke of inferiority will assert itself in our politics in creating a tyranny of injustice.”

Tagore had long rejected the bleak future offered by an imported idea of political unity without a moral foundation or vision of social unity that, as the tragedy of Kashmir testifies, degenerated into a debasement of human ideals by a morally blind nationalism:

“Even though from childhood I had been taught that idolatry of the nation is almost better than reverence for God and humanity, it is my conviction that my countrymen will truly gain their India by fighting against the education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity.”

Indeed, Tagore’s central premise was that the purpose of life was moral.

In a fitting tribute to Tagore, Isaiah Berlin wrote:

“It isn’t difficult to call for a return to the past, to tell men to turn their backs on foreign devils, to live solely on one’s resources, proud, independent, unconcerned. India has heard such voices. Tagore understood this, paid tribute to it, and resisted it.”

So did Kashmir. Rejecting its feudal past yet anchored in, and guided by its rich historical legacy of human and spiritual unity, Kashmir awaits a different future. History, collective memory and an abiding sense of a ‘different’ destiny remain Kashmir’s guiding moral and ethical markers in its ceaseless quest and thirst for liberty and justice. Yet, as Alan Paton wrote, “when that dawn will come, of emancipation from the fear of bondage and the bondage of fear, why, that is a secret” (Cry The Beloved Country).