Dispatches #173: Marrow matches, mango men and lost bitcoins

Thursday, 14 December 2017

Welcome to Dispatches, a weekly summary of my writing, listening and reading habits.This will be the final newsletter of the year – and the last one published before I start my new job as national music writer at The Australian on January 2 – so I'm including a few more recommendations than usual.

I'm unsure how Dispatches will fit into my new workflow, but I hope to continue sending this letter in some form in 2018, even if it's on a less regular basis (as I suspect may be the case).

Many thanks to all of you for reading, sharing and replying to Dispatches throughout the year, it's been a consistent highlight of my working weeks!

Words:

I wrote a post on Medium to summarise my eight years in freelance journalism, before I start my next chapter at The Australian. Excerpt below.

Never Rattled, Never Frantic (2,400 words / 12 minutes)To read the full story, visit Medium.

Staying motivated during eight years in freelance journalism

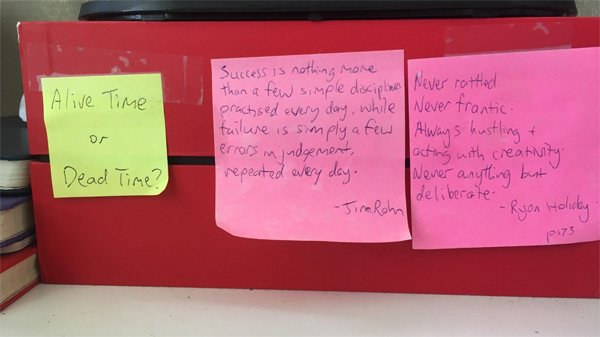

Underneath my computer monitor are three handwritten post-it notes that have been stuck in place for several years. They each contain a few words that mean a lot to me.

From left to right, they read as follows:

1. "Alive time or dead time?"

2. "Success is nothing more than a few simple disciplines practised every day, while failure is simply a few errors in judgement, repeated every day."

3. "Never rattled. Never frantic. Always hustling and acting with creativity. Never anything but deliberate."

Since I began working as a freelance journalist in 2009, aged 21, I have worked from eight locations: two bedrooms, two home offices, three living rooms, and one co-working space.

At each of these locations, I took to writing or printing quotes that I found motivational or inspirational. Most of them I have either absorbed by osmosis or outright forgotten, but there's one I found around 2011 that retains a special resonance. I printed it in a large font, and stuck it to my wall:

"Nothing in this world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not: nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is practically a cliche. Education will not: the world is full of educated fools. Persistence and determination alone are all-powerful."

That long quote was torn down and tossed during a move, but the message was internalised. If I had to narrow my success down to a single attribute, it's persistence. I could have quit on plenty of occasions, after any one of a number of setbacks. But I didn't.

In these motivational quotes, you may be sensing some themes.

I would be lying if I told you that the act of writing and affixing these quotes helped me on a daily, or even a weekly basis. I didn't repeat them out loud, like affirmations. Most of the time, they were as easy to ignore as wallpaper.

But often enough in recent years, during down moments, or in times of stress or upheaval, I'd shift my gaze from the words–or the bright, blank page–on the computer monitor, and find that these few handwritten notes would help to centre my thoughts.

Let me tell you why.

Sounds:

Leigh Sales interviews Paul McCartney (11 minutes). I loved this chat on stage before the first show of McCartney's Australian tour, and particularly Leigh's lovely statement toward him right at the end, which clearly catches him by surprise. Her delight at being in his company is irresistible. Leigh wrote a short article about the experience of meeting him here, and I also greatly enjoyed Zan Rowe's Take 5 interview with McCartney for triple j, where she got him to talk through how he wrote five of his greatest songs (45 minutes).

Match Made In Marrow on Radiolab (62 minutes). An intriguing, singular story about faith and science, and what happens when two people with entirely different worldviews are brought together in exceptional circumstances.One of the questions I'm most often asked is, "If you could interview anybody in the world, who would you pick?" It's a difficult question. When somebody asks it, they imagine that it must be a thrill to meet somebody of whom you are a huge fan. It is, of course, but it also comes with fear. What if the person is horrible? What if it's a bad experience? What if every time you then hear one of their songs, or read one of their books or watch one of their films, it's then a little bit soured by the fact you met them and they were mean or ill-mannered or egotistical? This happened to me when I interviewed the American author Jonathan Franzen in 2010 about his book, Freedom. I found him difficult from the first question. Now every time I consider re-reading The Corrections, one of my favourite books, all I think about is how snippy Jonathan Franzen was. If the question is really, "Of whom are you the most massive fan?", the answer is former Beatle, Paul McCartney.But do I want to interview him? His work means so much to me, do I really want to risk discovering that he's a Franzen? This week, I was forced to answer that question. My producer Callum rang me with a mind-blowing offer: McCartney will do his only television interview in Australia with you if you want to do it. When the offer came, it turned out it really wasn't a dilemma at all. It was a risk that simply had to be taken. As if any journalist could say no to the offer of an interview with one of the most influential musicians of the past century.

Chris Jones on The Sunday Long Read Podcast (95 minutes). A long conversation with one of my favourite magazine writers. I loved every minute of this. 10/10.You never know what might happen when you sign up to donate bone marrow. You might save a life... or you might be magically transported across a cultural chasm and find yourself starring in a modern adaptation of the greatest story ever told. One day, without thinking much of it, Jennell Jenney swabbed her cheek and signed up to be a donor. Across the country, Jim Munroe desperately needed a miracle, a one-in-eight-million connection that would save him. It proved to be a match made in marrow, a bit of magic in the world that hadn't been there before. But when Jennell and Jim had a heart-to-heart in his suburban Dallas backyard, they realized they had contradictory ideas about where that magic came from. Today, an allegory for how to walk through the world in a way that lets you be deeply different, but totally together.

The Butterfly Effect by Jon Ronson (7 episodes, ~3 hours). A podcast series about how the emergence of free-streaming porn sites resulted in unintended consequences for individuals and businesses around the world. Ronson is a great narrator, and I particularly liked the way in which this series shows how he goes about charming and winning the trust of his sources. The Butterfly Effect is fascinating, funny, and the final episode is unexpectedly moving. Recommended.In the middle of his Twitter hiatus, two-time National Magazine Award winner Chris Jones chats with Don Van Natta Jr. Jones shares behind-the-scenes details from his favorite stories–including profiles of Roger Ebert and Teller. He also explains why he's just now learning to cook and how he managed to expense both poker losses and marijuana.

Shame and Solutions on The Lucky Country (33 minutes). I have thoroughly enjoyed every episode of this series throughout 2017, and though I don't think I've mentioned it in Dispatches until now, I wanted to recommend episode 10, as it might be the best one to date. Richard Denniss is an economist and writer, and a clear thinker above all else. I really enjoy his conversational style of hosting, as he switches from sharing his thoughts on political trends and decisions affecting the whole of Australia, to one-on-one interviews with guests from inside politics and the public sector. This has been one of my favourite podcasts of 2017, and I look forward to Denniss and his team producing more great work next year.Welcome to The Butterfly Effect. It's sort of about porn, but it's about a lot of other things. It's sad, funny, moving and totally unlike some other nonfiction stories about porn - because it isn't judgmental or salacious. It's human and sweet and strange and lovely. It's a mystery story, an adventure. It's also, I think, a new way of telling a story. This season follows a single butterfly effect. The flap of the butterfly's wings is a boy in Brussels having an idea. His idea is how to get rich from giving the world free online porn. Over seven episodes I trace the consequences of this idea, from consequence through to consequence. If you keep going in this way, where might you end up? It turns out you end up in the most surprising and unexpected places.

'Hold My Hand' music video by Jen Cloher (7 minutes). It's been a while since I've seen a more perfect marriage of song and video than this. 'Hold My Hand' is about the way in which Alzheimer's disease strips memory and meaning from human life, and it's inspired by Jen Cloher's experience with caring for her mother in the final years of her life. Devastating and incredibly moving. On the same subject, I also loved reading Cloher's Letter To My U-Turn, which she first read aloud at Women of Letters in 2012.As the citizenship crisis plays out, the government is reaping the lack of trust that it itself has been sowing for years. Voters don't trust politicians because politicians have trained voters not to trust anybody. Throughout this series the issue of shame has come up again and again. To explore its effect on public debate and the economy, Richard Denniss talks to Jim Stanford from the Centre for Future Work about union membership and wage stagnation, broadcast Jeremy Fernandez about the courage of speaking up about a racial attack and Chris Fry on what's needed to change the gun debate in America.

J Mascis on Guitar Moves (17 minutes). One of the world's great guitarists shows how he learned to play the instrument, and how it took him 30 years to figure out palm muting.

NOISEY Bompton: Growing up with Kendrick Lamar (11 minutes). I loved this insight into Kendrick Lamar's neighbourhood, and how he seems to have kept many of his childhood friends from Compton despite becoming one of the world's most popular musicians.J Mascis–who's fronted Dinosaur Jr. since the band's 1984 inception and has directed the group through brilliant 11 studio albums–has made a musical world of towering mountains of feedback and distortion and deep valleys of aching melody. His use of the guitar as both a weapon and a hook machine has been the blueprint the past three decades of alternative rock, and his violent use of effects pedals is the stuff of countless gearheads' wet dreams. That sound of technical skills seamlessly blended with equal parts unhinged noise and heart breaking hooks set up the commercial success of bands like Nirvana and the Pixies. In this episode of Guitar Moves, Matt Sweeney has a action packed hang with the guitar wizard–who's traditionally not super talkative in interviews–and Mascis shines light on the origins of his guitar playing, Dinosaur Jr.'s influential sound, and gives an up close look at some of his favorite guitar moves.

Compton, California, is one of hip-hop's most celebrated locales, the birthplace of acts like N.W.A. and, more recently, Kendrick Lamar. It's also home to a complicated gang culture. Noisey Bompton centers around Kendrick Lamar and the friends he grew up with on the West Side of Compton, many of whom feature on the cover of his album 'To Pimp A Butterfly.' n the first of six segments, we sit down with Kendrick to talk about his acclaimed albums, pay a visit to his high school, Centennial, and get to know his childhood friend Lil L.

Reads:

The Long and Winding Way To The Top: Fifty (Or So) Songs That Made Australia by Andrew P. Street (2017, Allen & Unwin). Attempting to narrow the history of Australian popular music to just 50 songs that impacted the nation is a hugely challenging task, as author Andrew P. Street acknowledges in the introduction (and notes that his first list contained 476 tracks). Despite the difficulties of such decisions, however, Street has written a thoroughly entertaining and educational guide to the last 60-odd years of entertainment, starting in 1958 ('The Wild One' by Johnny O'Keefe and The Dee Jays) and ending in 2016 ('January 26' by A.B. Original featuring Dan Sultan). His writing style is arch and authoritative, and given the subjective nature of listening to music, Street is thankfully unafraid to call it as he sees it. For instance, he writes that a prog-jazz-fusion band named Ayers Rock "produced the absolute worst garbage I have ever heard in all of my life".

The Long and Winding Way To The Top manages to be both breezy and serious in its delivery. The chapters run to several pages each, and Street summarises not only the circumstances surrounding the creation of each song, but what else was happening in Australian popular and political culture at the time. Street is no stranger to political commentary, having filed daily columns for Fairfax Media for several years, as well as having published books about the nation's two most recent Prime Ministers. This book benefits enormously from his familiarity with that world, and in a sense, he's the perfect writer to combine his consuming interests in both music and politics.

Footnotes abound, as Street frequently laments songs and artists that he was forced to cull from the list. Above all, the author takes on the tone of an educator, and it works well. I learned a lot from his chapter concerning Powderfinger (and its song 'These Days'), for instance, where he notes that the band made "music for straight men to hug to", which strikes me as entirely true. As well, his chapter on The Drones ('Shark Fin Blues') examines the role of national myths about stoic and self-sufficient Aussie manhood, wherein "suffering from a mental illness like, for example, depression has not only been considered unmanly but also suspiciously un-Australian".

This book's accessibility will satisfy both casual and hardcore music fans, and the nation's literary and musical cultures are both richer for Andrew P. Street having turned his mind to that difficult task of culling 476 songs down to the 50 that made Australia.

The Great Australian Nightmare by Greg Callaghan in Good Weekend (5,200 words / 26 minutes). An exhaustive researched and engagingly written story about the dangers of inadvertently inhaling tiny asbestos fibres, and what Australian doctors and lawyers are calling the "third wave" of asbestos-related lung diseases that have been contracted through home renovation and indirect exposure. As one of Greg Callaghan's many sources reflects: "That blasted dust. If only we had all known."

Of Mice & Men by Greg Bearup in The Weekend Australian Magazine (4,000 words / 20 minutes). A great profile of Professor Sally Dunwoodie, whose miscarriage study was hailed as one of Australia's biggest medical research discoveries. Yet within 24 hours of the news being shared, she was at the centre of a global storm, thanks to the way in which Dunwoodie's research was framed in the press release. Greg Bearup asks, then answers: "So how did it come to this – that her painstaking work at a prestigious research institute is viciously attacked by some of her scientific and medical colleagues?"Like a snake's tongue, the flame curled across the floor of the large garage before spreading rapidly, fuelled by tins of paint thinner, solvents and then an LPG cylinder stored against a back wall. Perhaps ignited by a soldering iron that was left on, the fire swiftly chewed up a handful of exquisitely crafted model airplanes on a wooden bench, before devouring the gleaming, lovingly restored 1978 Ford Fairmont and ute parked behind it. For the first few minutes of the blaze, Joan Behrend, her husband Peter and his mate Don were chatting happily in the kitchen, the two men wolfing down a plate of sandwiches Joan had made for lunch, oblivious to the inferno underway behind the house. Neighbours, alerted by ribbons of smoke rising from the garage, called the fire department and were running across the road, yelling, "Fire, fire!" By the time fire crews reached the leafy street in Officer, a satellite suburb of Melbourne, flames were licking the back of their four-bedroom house. High winds on this hot, dry January day in 2008 fanned them; it took firefighters more than 30 minutes to protect the back of the house and extinguish the flames. Standing near the charred ruins of the garage, in the uncanny stillness that follows a fire, the Behrends were in shock. But it wasn't the loss of the prized, hand-made model airplanes or the Ford Fairmont that was racing through their minds. Only moments before, the chief fireman had approached them in his thick protective gear. "Your house is full of asbestos," he warned. "You've got to get out."

Window To The World by Tim Elliott in Good Weekend (2,600 words / 13 minutes). A beautiful, sensitively written profile of a 91 year-old woman who happens to be the final tenant in Sirius, a public housing block overlooking Sydney Harbour whose days are numbered. I love the way Tim Elliott ends this one.From her Darlinghurst office, Professor Sally Dunwoodie has a view over Sydney's party streets to boats bobbing on Rushcutters Bay. It's 10pm on a Friday, two days before last Christmas; the city is heaving, the harbour sparkles and Dunwoodie is hunched over her computer. The vista barely draws a glance. She is exhausted after months of distilling years of research into a scientific paper and is ill with a respiratory infection. She should be home in bed. Her voice is a croak but she and a colleague soldier on, preparing reams of documents to upload to the website of the world's most prestigious medical journal, The New England Journal of Medicine. Finally, she hits send and the product of more than a decade of meticulous work by Dunwoodie and her research team – many tens of thousands of hours of experiments, observations, thought and discussion – floats off in the humid night sky to Massachusetts. Two months on, Dunwoodie learns her paper has been accepted for publication by the journal. It's the scientific equivalent of winning an Oscar – of the many thousands of papers submitted each year by the world's leading researchers, only five per cent is accepted, and only after a rigorous anonymous peer review by five experts. It is only at this point that she begins to mull over the enormity of her discovery linking a deficiency of niacin, also known as vitamin B3, with birth defects and miscarriages. If her hypothesis works as well with humans as it does with mice, it has the potential to affect the lives of millions of people around the world. It's huge.

A Fine Death by Margaretta Pos in The Weekend Australian Magazine (2,600 words / 13 minutes). A beautiful story about what it's like to watch your father choose to end his life at home.Myra Demetriou has it all planned out. When she dies, which is going to be sooner rather than later given she's 91, her body will be shuttled to the University of Sydney, where it will be donated to science. There are two advantages to this, she tells me: It saves on the expense of a funeral, and it will help someone, somewhere: medical students, perhaps, or a scientist looking into longevity or maybe even a transplant patient who desperately requires a pair of arthritic knees. This is what gets Myra jazzed. Helping people. Any people. In 2014, she baked 96 scones for a picnic held by residents of Sirius, the social housing complex where she lives, in Sydney. Then, last year, she cooked up 24 Christmas puddings. Or was it 34 puddings? Doesn't matter. Either way, a lot of cakes got baked, and that was good. Myra has a long, slightly masculine face, with prominent eyebrows and a bold, unapologetic nose, the nostrils of which are so big you could park a truck in them. She does not prevaricate, she dominates. Her voice does not quaver, like those of many old people; it is loud and clear, a diamond-tipped instrument, tailor-made for punching holes in bullshit. She's got spurs in her ankles, osteoporosis in her knees, late-onset asthma and tinnitus. Her cholesterol is high but her blood pressure is low, meaning that she has to get up slowly otherwise she'll fall flat on her face, which she has done before and didn't enjoy one little bit. She is also legally blind, which makes changing the channel on the TV pretty challenging. So she leaves it on "Channel 2", and listens to it like a radio.

In The Name of Love by Jonathan Dean in The Weekend Australian Magazine (2,200 words / 11 minutes). A tough, fair profile of U2's singer, Bono. Worthy of note: this story attracted 200+ comments, which goes to show that plenty of people have an opinion about this guy, and most of them appear to be negative."It's been postponed," Sacha said. "Until Saturday." "What has?" I couldn't help asking, although I knew the answer. "Hugo's death." I stared at my sister-in-law. We were at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, where she had met me after the long haul from Tasmania. It was Tuesday night. "Why?" "The doctor was too busy on Friday night. He's giving flu shots to elderly people and won't have time and he couldn't make it on Thursday night either. So it's Saturday morning at 10." "Too busy?" She nodded and we clutched each other, shaking with hysterical, silent laughter. Six days earlier, my son and I were having dinner in Hobart with my Dutch half-brother Goshwin, who was visiting us, when the telephone rang. My son answered it. "Grandpa!" he exclaimed. He passed the handset to Goshwin, who listened, stiffening. "I'm coming back," he said in Dutch, and handed the phone to me. My father had been living with stomach cancer for two years but in recent weeks it had spread. He had difficulty speaking and his voice was a whisper. "There's no need to come," he said. "We saw each other only six months ago and had a wonderful time." This was true. Then, chillingly: "It's going to be soon, but this won't be the last time you hear my voice."

Meeting Mr Mango by Jonathan Seidler on Broadsheet (1,800 words / 9 minutes). A wonderfully written story about mangoes, and one man in north Queensland who's been growing and selling the fruit for 30 years.Recently, Bono has been worried about how he will be remembered when he dies. "The loss of David Bowie affected me profoundly," he says. "And Leonard Cohen, who I didn't know as well as David, but I knew Leonard." Both singers were given a vibrant send-off and the tributes were 99 per cent positive. That won't happen for Bono. "At your funeral, nobody talks about what you achieved," he says a little sadly. "They talk about whether you were funny or not. Were you kind to your kids? So I'm moving away from worrying too much about legacy, as regards U2 or my own work, to be more concerned about what my kids and friends think of me." I met Bono in Sao Paulo in October on the terrace of his hotel the day after another run-through of the band's classic 1987 album, The Joshua Tree, for their sellout 2017 anniversary tour. A woman in the crowd passed out. Models posed for selfies. Actor Owen Wilson was there, in bold floral trousers, singing his sad heart out to With or Without You. Four men thumped the night sky whenever U2 played a hit, which was a lot. When I mention those men to Bono, he asks if I have met Javier Bardem. That's how his conversation goes, a verbal rush through Who's Who. Bardem, he explains, is a "champion air drummer". He name-drops all the time, from "the Macca" (Paul McCartney) to his "quite close friend" Lena Dunham. He has a cluttered phonebook and a cluttered mind, too: answers come, but take an age to arrive.

'I Forgot My Pin': An Epic Tale of Losing $30,000 in Bitcoin by Mark Frauenfelder on Wired (6,000 words / 30 minutes). A thrilling lost-and-found ride through the limits of cryptocurrency storage technology. It's a brilliantly told story, and I hung on every word. Make sure you watch the video embedded at the end, after you've finished reading!Alvise Brazzale tells his wife I'm going to write a book about him. "Hey Noalene," he crows as she rides past on one of his farm's Gator utility vehicles. "You better be nice to me, aye. Jonno here is doing a book about me. It's 'gonna be a bestseller." Brazzale is the sort of character you could not make up. He may well hold the title of Australia's most interesting man; the tobacco-turned-mango farmer, the classic-Ford enthusiast, the Italian family man, the mentor, the mental-health campaigner, the motor mouth. There is so much to him I could spend all day talking to him, roaming his 70-hectare mango farm, and not get bored. "I'm in a bikie gang, mate. You heard of the Bandidos? I'm in the Mangeedos." We're each three Great Northern Lagers deep and the tape's been rolling for over an hour. The ginormous shed is currently empty, but next week 50 beneficiaries of Australia's Working Holiday Visa program will begin sorting, spraying, stickering and stacking enough mangoes to feed most of the east coast. But work rarely stops at Brazzale Mango Mareeba, not even for the star of a forthcoming tome that has no title or publisher. "When I started, there were only Aussies working and it was a nightmare, mate, a nightmare. In the '70s and '80s it was dropouts from the city. Hippies. Now they're much more respectful. Different kettle of fish completely." I fucking love mangoes. I once dedicated an entire column in this publication to them. I also have absolutely no idea how they get from a seedling to my supermarket, so I'm here in Mutchilba, a 90-minute drive inland from Cairns, to learn from the Brazzales, who have been growing these magical golden orbs for as long as I have been alive.

Cricket Has Lost Sight Of What Stokes Did in Bristol by Malcolm Knox in The Sydney Morning Herald (1,500 words / 8 minutes). I love sports journalism that is written in such a way to transcend the ordinary boundaries of sport, and explores larger social issues. This Knox piece is a perfect example of that, as he examines the violence recently perpetrated by English cricketer Ben Stokes, and what the cricket world's apparent tolerance of his behaviour says about the attitudes of those in charge of the sport. Knox writes: "Why do I take it to heart? I have friends who have lost a son to an intoxicated man throwing punches on the street. Cricket is only a game, and games end. The effects of extreme violence do not."In January 2016, I spent $3,000 to buy 7.4 bitcoins. At the time, it seemed an entirely worthwhile thing to do. I had recently started working as a research director at the Institute for the Future's Blockchain Futures Lab, and I wanted firsthand experience with bitcoin, a cryptocurrency that uses a blockchain to record transactions on its network. I had no way of knowing that this transaction would lead to a white-knuckle scramble to avoid losing a small fortune. My experiments with bitcoin were fascinating. It was surprisingly easy to buy stuff with the cryptocurrency. I used the airBitz app to buy Starbucks credit. I used Purse.io to buy a wireless security camera doorbell from Amazon. I used bitcoin at Meltdown Comics in Los Angeles to buy graphic novels. By November, bitcoin's value had nearly doubled since January and was continuing to increase almost daily. My cryptocurrency stash was starting to turn into some real money. I'd been keeping my bitcoin keys on a web-based wallet, but I wanted to move them to a more secure place. Many online bitcoin services retain their customers' private bitcoin keys, which means the accounts are vulnerable to hackers and fraudsters (remember the time Mt. Gox lost 850,000 bitcoins from its customers' accounts in 2014?) or governments (like the time BTC-e, a Russian bitcoin exchange, had its domain seized by US District Court for New Jersey in August, freezing the assets of its users). I interviewed a handful of bitcoin experts, and they all told me that that safest way to protect your cache was to use something called a "hardware wallet."

Everything and Nothing by David Free in The Weekend Australian Review (1,600 words / 8 minutes). To end Dispatches for 2017, I wanted to share one of the best book reviews I read this year. David Free provides an insightful, perceptive critique of Jimmy Barnes's latest memoir, Working Class Man, having also reviewed its antecedent Working Class Boy a year ago. (Also worthy of note: David Free wrote one of my favourite books of the year, Get Poor Slow. It's a novel whose protagonist is a bitter book critic!)So, Christchurch is a place where it is okay to get drunk and smash someone's eye socket. The Canterbury Cricket Association, acting for the people of the Canterbury region, is happy to be represented by someone the world has seen committing such acts. Who knows, very soon England might also be the kind of place where you can batter someone who is cowering or lying on the ground and, weeks later, wear your country's colours. And Australia will be a place that puts such creatures on show. Apparently, anything is excusable because of the perpetrator's talent with bat and ball, and because his cricket team and cricket followers, his cricket opponents and his cricket hosts, want him. Some think they need him. His return would make great theatre and maybe more competitive cricket. Perhaps he can save the Ashes, if not by winning them for his team then by boosting the spectacle. Great for cricket! Blah, blah, blah, cricket. Cricket is so important. Zero tolerance for violence ... until the Ashes, when decision-makers find their weasely ways of tolerating it after all. If that's what cricket has come to, a game so arrogant that it has forgotten it is only a game, so consumed with its own insular theatrics, then you can shove your cricket.

++Last year Jimmy Barnes published Working Class Boy, the opening instalment of a memoir that proved too long, and too thorny, to be contained in a single volume. That first book, which broke off just as Barnes was joining a nascent Adelaide band called Cold Chisel, was astonishing in several ways. It told the story of a childhood that seemed to have been ripped from the most baroquely grim Dickens novel and transplanted to the suburbs of 1960s Australia. And it found a starkly effective language in which to tell that story: a stripped-back prose, full of jagged stops and starts. Is Barnes's second volume of memoirs as good as the first? Well, it's certainly less hair-raising. Then again, it could hardly fail to be. In that first volume, Barnes had the element of surprise going for him. None of us knew what his childhood had been like. And we had no right or reason to expect the arse-kicking rocker would suddenly turn out, at 60, to be a first-rate writer. He didn't just describe hunger and cold and violence; he made you feel them.

Thanks for reading. If you have feedback on Dispatches, I'd love to hear from you: just reply to this email. Please feel free to share this far and wide with fellow journalism, music, podcast and book lovers.

Andrew

--

E: [email protected]

W: http://andrewmcmillen.com/

T: @Andrew_McMillen

If you're reading this as a non-subscriber and you'd like to receive Dispatches in your inbox each week, sign up here. To view the archive of past Dispatches dating back to March 2014, head here.

Congrats for your new job! Your article on Wired about steemit drived me here! Thanks for writing these good pieces ;-)

Thanks for your beautiful post sharing.resteem it.

thanks for sharing your content..i think that your great creator..best of luck..

i hope this post is long more than any other post in steemit..

Nice post , follow me please

wow Nice story. I read the full story. your Story was Awesome.