Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland – Part 9

Before I begin to examine Claudius Ptolemy’s description of Ireland item by item, there are a few loose ends I would like to tie up.

Trying to match names in Ptolemy’s Geography with the geographical names one finds on modern maps of Ireland is fraught with difficulties. Among these, the following are worthy of note:

Ptolemy’s names have been Hellenized, as though they are Greek.

Ptolemy’s text is corrupt and full of misreadings.

In Ptolemy’s Ireland, the languages and dialects spoken were quite different from Modern Irish.

Toponyms and other geographical names change over time as the local vernacular changes.

Greek or Irish?

One of the fundamental postulates of the Short Chronology when applied to the early history of Ireland is that Ireland is a Celtic land: its early colonizers were Celts, and they spoke Celtic languages. In these articles I have repeatedly asserted that there were no pre-Celtic inhabitants of this island—at least not since the end of the last Ice Age. The pre-Celtic hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic Era and the pre-Celtic farmers of the Neolithic Era never existed. The archaeological evidence that has been assigned to these fictitious peoples actually belongs to the Celts and is much younger than mainstream archaeologists believe. Similarly, the warriors of the so-called Bronze Age were Celts and they belong to a period of history when Alexander the Great was already cold in his grave.

It follows that the original language of all the names in Ptolemy’s description of Ireland was Celtic. But when these names were recorded—whether by foreign voyagers or by Ptolemy himself—they were given Greek grammatical endings. The tribal names have endings characteristic of the nominative plural in Greek. The promontories and settlements are in the nominative singular. Because the rivers are recorded as Mouth of the X, they are generally in the genitive singular. But Ptolemy—or his source—was not consistent in this practice, as T F O’Rahilly noted:

These river names are in the genitive, governed by ἐκβολαι [mouth]; but names ending in α¬ are, for whatever reason, left undeclined by Ptolemy. (O’Rahilly 2 fn 1)

By Hellenizing the native Celtic names, Ptolemy himself initiated the process of textual corruption.

How Corrupt is Ptolemy’s Text?

If T F O’Rahilly was correct when he argued that Ptolemy’s principal source of information on Ireland was almost five hundred years old when Ptolemy made use of it—and I believe he was—then it follows that the actual text used by Ptolemy was probably a copy of a copy of a copy ... of an original document that was created in the late 4th century BCE. And our oldest manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography only goes back to about 1295, so it was probably a copy of a copy of a copy ... of Ptolemy’s original autograph. That’s a lot of opportunities for misreadings and typographical errors to creep in.

This is especially true with regard to a remote and little-known place like Ireland. It is fair to say that most if not all copyists of Ptolemy’s Geography were completely ignorant of the geography of Ireland. They would not have recognized as errors any glaring typos they came across, let alone have had the erudition to correct them. And if they had had any difficulty reading a particular name, they would have had no way of making even an educated guess as to the correct form.

Given all of this, it is a wonder that any of the names in Ptolemy’s description of Ireland bear the slightest resemblance to modern Irish names. After listing forty-nine of the Irish items in Ptolemy, T F O’Rahilly noted:

Of most of the above names there is no trace in our native records.

It is worth remembering that in every extant manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography the name of the River Thames is misspelled Iamesa (van Deukeren). If an error of this magnitude could pass unnoticed at a time when the Thames was part of Roman Britain, how likely is it that any errors relating to Ireland would have been identified and corrected?

Celtic

If Ptolemy’s principal source for Ireland dated back to about 325 BCE, then we should not expect to find any Irish (ie Gaelic) names in the Geography. The Irish language, or its immediate parent language, was the native tongue of the Goidelic Celts, who colonized Ireland quite late in the island’s history—between 150 and 50 BCE according to O’Rahilly’s model (O’Rahilly 208). Before that, the Celtic languages and dialects spoken in Ireland were more akin to Old Welsh than to Old Irish. People often forget this, if they know it at all. I am always being told that my given name, Brendan, is a borrowing from Welsh, when it is in fact pre-Gaelic Irish.

The last word has not yet been said concerning the origin and evolution of the Celtic family of languages. O’Rahilly, who continues to inform my views, was a staunch champion of the so-called P/Q Hypothesis. According to this theory, after Proto-Celtic broke away from Indo-European, it underwent several phonetic changes, one of which was the evolution of the initial p sound into a k or q sound. Subsequently, however, some Celtic dialects reversed this change and reinstated the p sound, while others retained the initial q (spelt c). In Middle Welsh, for example, the word for head is penn, whereas in Old Irish it is cenn.

That the division of Celtic into P- and Q-dialects is at least as old as the fourth century B.C. may be inferred from the name Πρετανοί [Pretanoi], which was almost certainly employed by Pytheas, and may go back to the sixth century B.C. ... it is quite possible—some might say probable—that the change from q to p is considerably older than the sixth century B.C.; but the question is really insoluble, for we have no evidence one way or the other. (O’Rahilly 429 fn 2)

In O’Rahilly’s model, P-Celtic was the native form in Ireland until quite late:

There were four bodies of Celtic invaders, viz. (I) the Priteni, who spread over Britain and Ireland; (II) the Bolgi, or Belgae, who invaded Ireland from Britain; (III) the Laginian tribes, who came from Armorica, and who appear to have invaded Britain and Ireland more or less simultaneously; and (IV) the Goidels, who reached Ireland direct from Gaul. The earlier invaders were P-Celts; the Goidels alone Q-Celts. The invasion of the Bolgi occurred perhaps in the fifth century B.C.; those of the Lagin and the Goidels between the time of Pytheas (ca. 325 B.C.) and the year 50 B.C. (O’Rahilly 419-420)

Once Irish had taken root, the older pre-Goidelic dialects gradually became extinct. There are references in our native records to the Iarnbélre, or Language of the Érainn, the latter being the most powerful and widespread of the Bolgi (O’Rahilly 85-91). As for the toponyms of the island, it is probably safe to assume that some were replaced by new Goidelic forms, some were Goidelicized, and some were preserved largely unchanged.

Change

Languages change over time. That is why there are so many mutually incomprehensible languages throughout the world. Even very closely related dialects can diverge significantly over a few centuries. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, dialects of Low Latin quickly evolved into the modern Romance languages, which, while closely related, are not mutually comprehensible.

By studying these changes, linguists can derive rules that allow them to reconstruct with some degree of certainty the original forms. One of the lasting achievements in this field is the classic text Handbuch des Altirischen, or A Grammar of Old Irish, by the Swiss Celticist Rudolf Thurneysen. In this weighty and scholarly tome, Thurneysen discussed the origin of Irish sounds and how the vowels and consonants of Old Irish evolved from those of Indo-European and Proto-Celtic. The following list tabulates some of his discoveries, but this subject is too involved for anything more than an abridgment. A close study of Thurneysen’s text is required for a proper understanding of this complex subject:

| Old Irish | Indo-European or Celtic | §§ in Thurneysen (1998) |

|---|---|---|

| c | k, q, qw | 183 |

| ch | k, q, qw, γ | 183, 124, 130-131 |

| cht | g+t, pt, b-t | 183, 227 (c), 228 |

| g, c | g,, gh, Ʒh, gwh, nk, γ | 184, 208, 129 |

| t, th | t, th, δ, d+ṡ | 185, 124, 130-131, 139 |

| d, t | d, dh, nt, t, z, th | 186, 208, 178:2, 218, 126, 128 |

| p, f, ph | b+ṡ, w, β, sw, sp, p | 187, 202, 124, 132, 226, 231:5 |

| b, p | b, bh, g, gw, w, f, -ph_ | 188, 227 (e), 201, 130, 635 |

| n | n, -m | 189, 176 |

| m | m, b | 190 |

| n | n, m | 191 |

| r | r, l | 192 |

| l | l, r | 193 |

| s | s, ss | 194 |

| ă | ă, a, o, e | 50, 81-82, 83a |

| á | ā, ō | 51 |

| e | ĕ, ĭ, ïa | 52, 73-74, 79, 106 |

| é | ei, ĕ, ă | 53-56 |

| i | i, ĕ | 57, 75-79 |

| í | ī, ē | 58 |

| ŏ | ŏ, u, a | 59, 73-74, 80 |

| ó | ou, eu, au, ow’, ŏ, ŭ, áu, op, ap | 60-63, 73, 69, 227 (f) |

| ŭ | ŭ, o, a | 64, 75-79, 80 |

| ú | ū, ŭ, áu | 65, 69 |

| aí | ai, oi, o+e, o+é, o+i | 66-67 |

| áe | ai, oi, o+e, o+é, o+i | 66-67 |

| oí | ai, oi, o+e, o+é, o+i, owi, owe | 66-67 |

| óe | ai, oi, o+e, o+é, o+i | 66-67 |

| uí | uwi | 68 |

| áu | au, ōu, ă+u, ā+u, ăw, āw, óu | 69, 72 |

| éu, éo | e+u, ew’, iw-, é | 70, 73, 55 |

| íu | i+u, é | 71 |

| óu | ow’, ow-, ew-, o+u | 72 |

Source: Rudolf Thurneysen, A Grammar of Old Irish

As I mentioned above, Old Irish was probably not spoken in Ireland when Ptolemy’s principal informant visited the island, so I do not know how useful Thurneysen’s rules are. O’Rahilly regularly applied them to words in Modern Irish (after 1200 CE), Middle Irish (800-1200) and Old Irish (before 800) in order to deduce what the original Celtic or Indo-European form may have been. For example:

Argita. If Vidva be the [River] Bann, Argita can only be the Bush, in the north of Co. Antrim. The name is probably related to O. Ir. argat, < *argento-, “silver”. (O’Rahilly 6)

In deducing that the Old Irish word argat derives from the hypothetical Proto-Celtic argento-, O’Rahilly was drawing on Thurneysen §83 (a) and §208:

§83. (a) Before palatal consonants e is often replaced by a ... §208. Nasals are lost before t- and k- sounds. (Thurneysen 53 ... 126)

To be continued ...

References

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

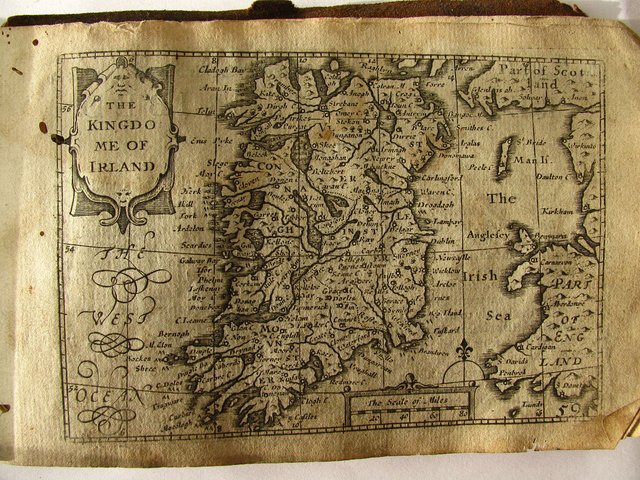

Image Credits

- John Speed’s Map of Ireland (1611): Wikimedia Commons, John Speed (cartographer), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Rudolf Thurneysen: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

You received a 10.0% upvote since you are not yet a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "archaeology".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

What is celtic .i am sorry i know nothing about ireland.but every country had some history

Great history. Thanks for sharing us.

very nice history.. excellent post

my dear friend @harlotscurse.

i love your post all time thank you for sharing with us,

Really very interesting the history of Ireland, a very didactic and enlightened way to get to know her, congratulations for her work.

I find the work that Rudolf Thurneysen had very interesting, very hard work my dear friend, I wish you good luck and many greetings!

very interesting the history of Ireland...

my dear friend @harlotscurse.

i like your post all time, thank you sharing your post..

Very good history and good article and photography dear @harlotscurse

Very Educational post dear @harlotscurse

Every country has a history. I know much about Ireland today through this post. . Wonderful history of Ireland. . Thanks for share

Before your post i have no idea about this history. Thanks for sharing.