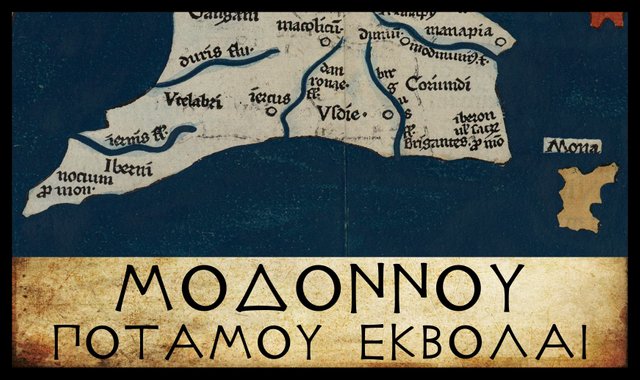

Μοδοννου Ποταμου Εκβολαι

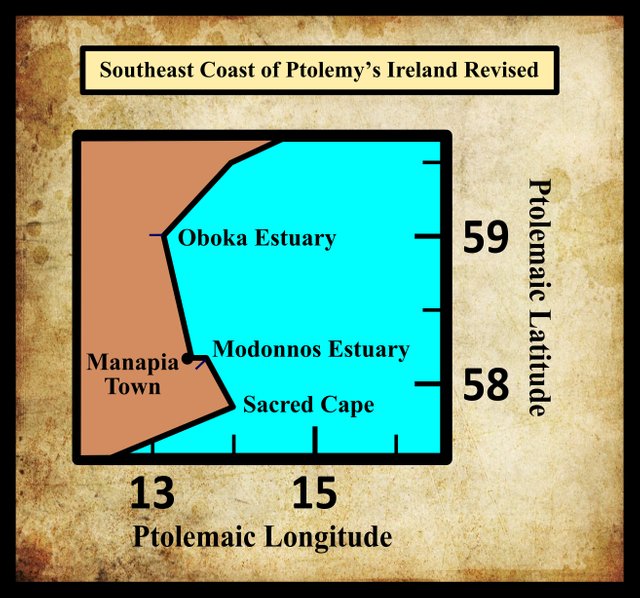

Proceeding in a counterclockwise direction around the coast of Ireland, the first landfall after Ptolemy’s Sacred Cape (Ιερον Ακρον) is Μοδοννου Ποταμου Εκβολαι, or Mouth of the River Modonnos. In order to correctly identify this landmark, it is necessary to examine four adjacent places on the east coast:

| Greek | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|

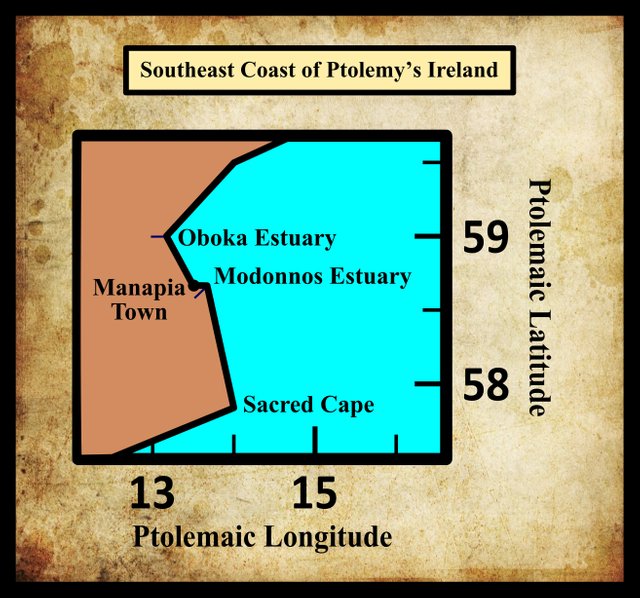

| Ιερον Ακρον | Sacred Cape | 14° 00' | 57° 50' |

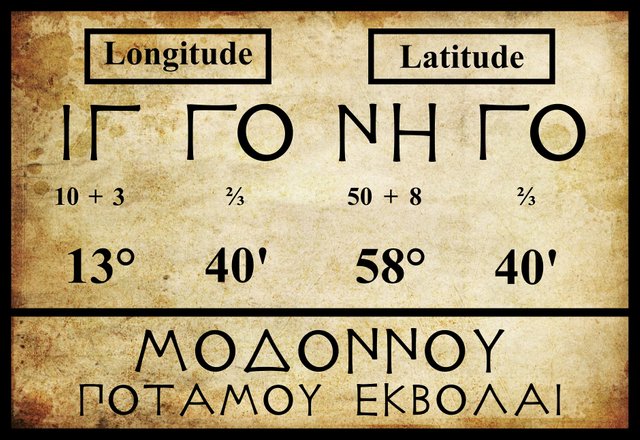

| Μοδοννου Ποταμου Εκβολαι | Mouth of the River Modonnos | 13° 40' | 58° 40' |

| Μαναπια πολις | Manapia Town | 13° 30' | 58° 40' |

| ’Οβοκα Ποταμου Εκβολαι | Mouth of the River Oboka | 13° 10' | 59° 00' |

In the previous article, I identified Ptolemy’s Sacred Cape with Carnsore Point, the most southeasterly point on the Irish coast. Most experts agree with this, but the identity of the three other landmarks is still a matter of scholarly debate. In the 18th century, researchers were so confident that Ptolemy’s Oboka referred to the Avonmore, the river that flows into the Irish Sea at Arklow, that they renamed the lower course of this river the Ovoca. The name stuck, but in the 19th century it was replaced by the present Avoca in the mistaken belief that this was the correct form (Dempsey 11-14).

If Ptolemy’s Oboka is the Avoca, then the Modonnos must be the Slaney, but no consensus has ever been reached on the matter, and today scholarly opinion favours the River Liffey as the Oboka. Over the centuries the Modonnos has been variously identified with the Liffey, the Avoca, the Slaney, and even the River Moy in Connacht:

| Slaney | Avoca | Liffey | Moy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - | - |

| Ware (1654) | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | O’Conor (1766) |

| Lewis (1837) | - | - | - |

| Orpen (1894) | - | - | - |

| - | - | Martin (1910) | - |

| - | O’Rahilly (1946) | - | - |

| Mac an Bhaird (1991-93) | - | - | - |

| - | - | Francis (1994) | - |

| - | Duffy (2000) | - | - |

| Stempel (2002) | - | - | - |

| - | Darcy & Flynn (2008) | - | - |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 57

In an earlier article, I pointed out that the River Slaney is one of the principal waterways of Ireland, one that every Irish child learns of at an early age. The River Avoca, however, is not so well known. I cannot believe that Ptolemy would have included the latter while omitting the former. The mouth of the Slaney is only about 20 km from Carnsore Point, which in turn is about 500 km from the European mainland. In Ptolemy’s day, it probably took three or four days to sail from Europe to Ireland with favourable winds, and twice that with unfavourable winds (Casson 138-143). Wexford Harbour, at the mouth of the Slaney, would have provided weary sailors with an ideal harbourage, where they could have recovered from the crossing and taken on fresh water. They could not possibly have overlooked it.

But if Ptolemy’s Modonnos is the Slaney, why have so many scholars rejected this identification? Because on Ptolemy’s map, the Modonnos is too far north to be the Slaney.

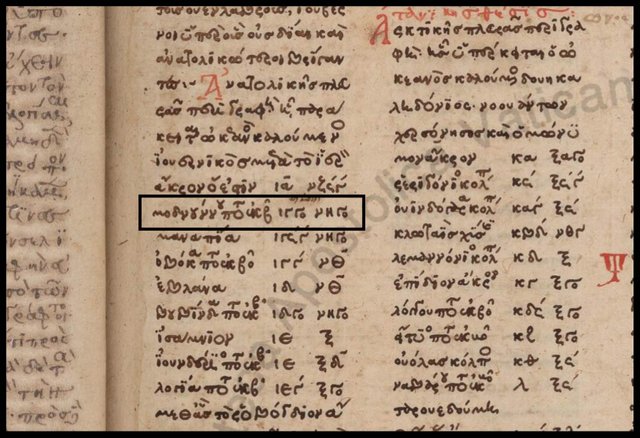

Is it possible that the Modonnos and Manapia have simply been misplaced? If they have, the error must have been made a long time ago—possibly by Ptolemy himself. If the misplacement had been first made by one of Ptolemy’s copyists, it would have been replicated on some but not all of the manuscript sources of the Geography. But the principal editions and all the early extant sources assign the same coordinates to the Modonnos:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | 13° 40' | 58° 40' |

| Wilberg | 13° 40' | 58° 40' |

| Nobbe | 13° 40' | 58° 40' |

| Vaticanus graecus 191 | 13° 40' | 58° 40' |

Revising Ptolemy

We do not know what source or sources Ptolemy used when compiling his geographical description of Ireland. He may have simply copied a list of landmarks and their coordinates from Marinus of Tyre, the Phoenician cartographer whose work he is known to have drawn upon. Or he may have had a copy of an original periplus—perhaps the one compiled by Pytheas of Massalia, who is believed to have visited Ireland around 325 BCE (Tierney 259). Such a document probably contained a record of Pytheas’s voyage: the ship’s log, or a set of sailing directions abstracted from the log, or a narrative of his voyage. Taking inspiration from the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, we might surmise that it contained something along the following lines:

Having reached the southeastern point of Ireland, we followed the coast, which trends towards the north. After half a day’s course, the shore receded into a bay at the mouth of a large river, known locally as the Modonnos. On the river, about forty stadia to the west of the mouth, stands the market-town of Manapia, where the Irish bring their wares to trade with merchants from abroad. Sailing north along the coast for one day, we next came to a large bay into which the river Oboka, debouches ...

It would have been quite easy for a careless copyist to interchange the two figures—half a day and one day—with the result that Modonnos and Manapia were placed too far to the north, while retaining their proximity to each other. I will be looking in detail at Manapia in the next article, but the mouth of the Slaney, lying in the southeast of the island and sheltered from the sea by Wexford Harbour, would have been an ideal place for Irish and foreign traders to exchange their wares.

This revision is a little closer to the actual geography of the Irish coast, but it is still not particularly accurate. My argument, moreover, is entirely speculative, so I will not pursue it any further.

The Literature

The name of this landmark, which Ptolemy gives in the genitive case (governed by εκβολαι : outlet, mouth [of a river]), varies only a little among the sources:

| Greek | English |

|---|---|

| Μοδοννου | Modonnou |

| Μοδονου | Modonou |

| Μοδνουννου | Modnonnou |

| Μοδνυννου | Modnunnou |

Anthony Durham and his associates on the website Roman Era Names are satisfied that Modonnos is of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origin:

Μοδονου (or Μοδουννου) river mouth (Modonu 2,2,8) was the river Slaney into the harbour at Wexford, whose name originated as Old Norse for its mudflats. Words such as Dutch modder “mud” probably descend from PIE *meu-, also the apparent source of [Old Irish] muad, a word with many meanings including “damp”, which named the river Moy (at the other end of Ireland). (Durham et al)

It is interesting to find modern linguistic scholars connecting Ptolemy’s Modonnos with the Old Irish word muad, from which the River Moy takes its name. In 1766, O’Conor surmised that Ptolemy’s Modonnos was the Moy, which had been misplaced.

In his 1745 edition of the works of James Ware, the antiquarian Walter Harris added a fanciful etymology of his own to Ware’s brief account of the Modonnos:

Modonus, a River: The old Name is grown out of Use, and it is now called the River Slainy, in the County of Wexford, as the Situation in Ptolomey points out to us. [Harris: The word Modonus may be drawn from two Irish Words. Modh-ean, that is the greater Water, this being the greatest River in that Tract. (Ware & Harris 55)

Goddard Orpen was one of the first scholars to argue that Ptolemy had omitted to mark the mouth of the Slaney. Initially, however, he had identified the Modonnos with the Slaney and the Oboka with the Avoca:

On the east coast the river Μόδοννος, the first river mentioned north of the Sacred Promontory or Carnsore Point, is probably the Slaney, as so important a river is not likely to have been omitted, though it is placed much too far from Carnsore Point ... The ’Οβόκα is probably the Ovoca at Arklow, but the modern name has been adapted from Ptolemy. (Orpen 1894:124 ... 125-126)

In a paper published almost twenty years later, however, Orpen revised his opinion:

It has usually been supposed that Manapia was on the site of the town of Wexford, but this supposition seems to be based on no better ground than that the river Modonnus, near the mouth of which, according to Ptolemy, Manapia was situated, is the first river-mouth marked by Ptolemy north of the Hieron Akron, or south-eastern point of Ireland (Carnsore Point). But if we compare the relative positions of the places marked on Ptolemy’s map between Hieron Akron, or Carnsore Point, and the Buvinda, or Boyne (identifications which seem certain), with the actual east coast of Ireland, we are forced to the conclusions that Ptolemy has omitted to mark the mouth of the Slaney, that his Modonnus is the Ovoca at Arklow, and that his Oboka is the Vartry at Wicklow. (Orpen 1913:51-52)

Orpen was led to this change of heart by the fact that Ptolemy placed two tribes—the Coriondi and the Brigantes—south of the Manapii of Manapia. But if Manapia was at Wexford, then this does not leave enough room for the Coriondi and the Brigantes. This is a strong argument, and I will return to it when I discuss Ptolemy’s Irish tribes.

T F O’Rahilly agreed with Orpen that the Modonnos was the Avoca, but he too accepted the Indo-European origins of the name:

Modonnos probably represents the river (miscalled Ovoca in English) which enter the sea at Arklow ... The form of the name reminds one of Modarn ... the name of the River Mourne and its continuation the River Foyle ... In case Modarn goes back to Modornā, -nos, we might suppose Ptolemy’s Μοδοννου to be a corruption of Μοδορνου. [Footnote: Equally well, of course, Modarn might go back to *Mudornā, -nos, or the like, and be cognate with Muad, the River Moy (IE. root meu-d-).] (O’Rahilly 4, fn 1)

In Ptolemy’s day, the letters nu (n) and rho (r) were not particularly similar, so O’Rahilly’s supposition is unlikely though not out of the question. The two letters are not entirely different:

It is hardly a coincidence that the Norse founders of Wexford should have named their fledgling city after the mudflats at the mouth of the Slaney: Veisafjǫrðr, “fjord of the mudflats”.

This town, which, as far as can be inferred from the earliest historical notices respecting it, was a maritime settlement of the Danes, is thought to have derived its name, which was anciently written Weisford, from the term Waesfiord (Washford), which implies a bay overflowed by the tide, but left nearly dry at low water, like the washes of Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire. (Lewis 707)

To this day, the estuary of the Slaney is noted for its extensive mudflats. The mouth of the Avoca, on the other hand, is not noted for its mud.

References

- Lionel Casson, Ships under Sail in the Ancient World, Transactions of the American Philological Association, Volume 82, pp136‑148, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (1951)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Rev P Dempsey, Avoca: A History of the Vale, Browne & Nolan, Ltd, Dublin (1912)

- Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, S Lewis & Co, London (1837)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Goddard H Orpen, Rathgall, County Wicklow: Dún Galion and the “Dunum” of Ptolemy, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Volume 32 (1914-16), pp 41-57, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1913)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Wilfred H Schoff, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Longmans, Green, & Co, New York (1912)

- J J Tierney, The Greek Geographic Tradition and Ptolemy’s Evidence for Irish Geography, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Volume 76, pp 257-265, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1976)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- River Slaney above Ferrycarrig: Geograph Ireland, © David Hawgood, Creative Commons License

- The Mouth of the Slaney at Wexford: Geograph Ireland, © Chris, Creative Commons License

i like your article dear

thanks for share for this history..

@upvote done

I am your new follower.

you write so nice history dear.

@upvote done

hi dear @harlotscurse...

how are you?..

great history...and very nice post... i like this post...

thank you so very much for sharing with us D:)

i just #resteem and #upvote

Excellent story thanks for sharing it with us

informative post.....

And great history....

thank you so very much for share...dear .@harlotscurse...

So i just

@upvote & @resteem done

Wow very nice history,...

and very good post...

dear @harlotscurse...

I jost resteem and upvote..done..

Thank you so very much for share..

informative post..

thank you..@harlotscurse

@upvote & @resteem done

its a learing post..

you learn us a lot..

@upvote & @resteem done

hi dear @harlotscurse...

how are you?..

Dear your great history...and very nice post... i like this post...and i really love you all time..

thank you so very much for sharing with us D:)

i just #resteem and #upvote